Early Life

Even while Swamiji (Swami Vivekananda) was in the midst of his arduous labours in the West, he realised that more important work was awaiting him in India. When the great leader returned to the motherland and made his triumphal tour from Colombo to Almora, it was in the city of Madras that he first intimated to eager listeners his plan of campaign. Some of the citizens approached Swamiji with the request that he should kindly send one of his brother disciples to stay in Madras and establish a monastery which would become the centre of the religious teachings and philanthropic activities outlined by Swamiji in his addresses delivered in India and abroad. By way of reply he said,

I shall send you one who is more orthodox than your most orthodox men of the South and who is at the same time unique and unsurpassed in his worship of and meditation on God.

The very next steamer from Calcutta brought to Madras Swami Ramakrishnananda.

In a few words the leader had summarized the individual characteristics of the apostle in relation to the field of work for which he was chosen. South India has all along been the stronghold of orthodox Hinduism. In order to infuse new life into the ancient religion without breaking the continuity of the tradition, the apostle to the South had to be a person of great intellectual attainments, of unflinching devotion to the ideals, and of deep reverence for the forms of worship and religious practices sanctified by the authority of a succession of great teachers. Swami Ramakrishnananda or Shashi Maharaj, as he was familiarly called, possessed all these and, in addition, he had an overflowing kindness, abounding sympathy for all, and a childlike nature which exhibited the inner purity of the soul.

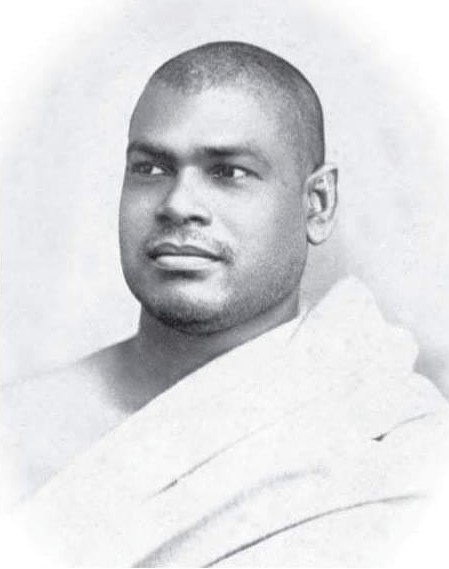

Shashi Bhushan Chakravarti—that was the name by which Swami Ramakrishnananda was known in his pre-monastic days—was born in an orthodox brahmin family of the Hooghly district, Bengal, on 13 July 1863. His father, Ishwarchandra Chakravarti, a strict observer of religious traditions and a devout worshipper of the Divine Mother, gave the early training that laid the foundation of the lofty character exhibited in the life of his great son.

Shashi went to school, and having successfully completed the school course, entered the Metropolitan College in Calcutta. He was a brilliant student at college and his favourite subjects were literature (both English and Sanskrit), mathematics, and philosophy. He and his cousin Sharat Chandra—afterwards Swami Saradananda—came under the influence of the Brahmo Samaj. Shashi became intimately known to the Brahmo leader, Keshab Chandra Sen, and was appointed private tutor to his sons.

With Sri Ramakrishna

On a certain day in October, 1883, Shashi and Sharat, along with a few other boy-companions, arrived at Dakshineswar to see the Master. Sri Ramakrishna received them with a smile and began to talk to them warmly about the need of renunciation in spiritual life. Shashi was then reading in the First Arts class and the others were preparing for matriculation. As Shashi was the oldest of the band, the conversation was addressed to him. Sri Ramakrishna asked Shashi whether he believed in God with form or without form. The boy frankly answered that he was not certain about the existence of God and was not, therefore, able to speak one way or the other. The reply pleased the Master very much. Shashi and Sharat were fascinated by the personality of Sri Ramakrishna whom they henceforth accepted as their Master, the pole-star of their lives. Of Shashi and Sharat, Sri Ramakrishna used to say that both of them were followers of Jesus Christ in a former incarnation.

Although Shashi was a brilliant student, his interest in the college curriculum began to dwindle. Slowly and silently he was progressing in the life of the spirit. His keen intellect, robust physique, and steady character were beginning to centre round the one grand theme of God-realisation. One day at Dakshineswar it happened that he was busily engaged in studying some Persian books in order to read the Sufi poets in the original. The Master had called him thrice before he heard. When he came, Sri Ramakrishna asked him what he had been doing. Shashi said that he was absorbed in his books. He quietly remarked, ‘If you forget your duties for the sake of study, you will lose all your devotion.’ Shashi understood. He took the Persian books and threw them into the Ganga. From that time on book-learning had little importance in his scheme of life.

Shashi was then in the final B A class; the examination was fast approaching. But at that very time Sri Ramakrishna was lying ill at Shyampukur in Calcutta. The young disciple had to decide between his studies and service to the person of the Master. Unhesitatingly he decided to give his body, mind, and soul wholly and unreservedly to the service of the Master. He also followed the Master to the Cossipore garden-house. Shashi was the very embodiment of service. Other disciples also gave their very best in the service of the Master. But Shashi’s case was conspicuous. He knew no rest. He did not care for any other spiritual practice. Service to the guru was the only concern of his life. Fortunately, he was endowed with a strong physique. But more than that, behind the body, there was a mind whose strength was incessantly sustained by his love and devotion to the guru. Till the last moment of the earthly existence of the Master, Shashi was unflagging in his zeal to serve him as best as he could. Before Sri Ramakrishna lay down for the final departure, he sat up for some time against some five or six pillows which were supported by Shashi, who was at the same time fanning him. When the Master was in Mahasamadhi, the disciples could not at first realise what it was. Shashi rebuked those who thought that it was otherwise than samadhi, and along with others began to chant holy texts. But despite their earnest hope the body did not indicate any sign of life, and the doctor finally declared it to be Mahasamadhi.

The greatest trial was at the burning ghat. Feelings of a contrasted character visited the soul of Shashi. Now the joy and bliss the Master had shed over them all came over him and he sang the name of the Master in triumphant praise. Then a sense of utter loneliness stole over his joy and made him the victim of most violent grief. When the flames that had made ashes of the body of the Master had died out, amidst the silence that prevailed, Shashi gathered the sacred relics.

At the Barnagore and Alambazar Monastery

Then came the period of supreme depression. The boys who were children of the Master gathered together at the newly founded monastery at Baranagore. Shashi played no small part in holding the young band together and in regulating the routine of life to be followed by them. While others were indifferent as to whether the body lived or died in their intense search for the Highest, Shashi took care that his brother disciples had not to face actual starvation. He went so far as to serve as a schoolmaster—though for a very short period—to meet the expenses of the Math. He would say to his brothers, ‘You just continue your spiritual practices with undivided attention. You need not bother about anything else. I shall maintain the Math by begging.’ Swamiji, recalling these blessed days many years later, said with reference to Swami Ramakrishnananda, ‘Oh, what a steadfastness to the ideal did we ever find in Shashi! He was a mother to us. It was he who managed about our food. We used to get up at three o’clock in the morning. Then all of us, some after bathing, would go to the worship room and be lost in japa and meditation. There were times when the meditation lasted to four or five o’clock in the afternoon. Shashi would be waiting with our dinner; if necessary, he would by sheer force drag us out of our meditation. Who cared then if the world existed or not!’

The parents of the boys came and attempted to take them back to their homes, but they would not yield. Shashi’s father came, begged and threatened, but to no purpose. The son said, ‘The world and home are to me as a place infested with tigers.’ The time came when the boys decided to renounce the world formally by taking the monastic vows. They changed their names. Shashi became Ramakrishnananda. Narendranath, the leader of the young band, wanted to have that name for himself but thought that Shashi had a better claim to it because of his unparalleled love for the Master. Indeed Shashi’s love for the Master sounds like a story, nay, has passed into stories. Death could not rob him of the living presence of the Master. He served the Master in the relics with the same devotion and earnestness as when he had been physically alive. Others went on pilgrimages, adopting the wandering life of the monk. Swami Ramakrishnananda stuck like a sentinel on to the holy spot where the Master’s relics were temporarily enshrined. Worshipping the Master and keeping the monastery as the centre to which the wanderers would occasionally return were the duties which Ramakrishnananda assigned to himself. He did not think of going to a single place of pilgrimage. What place under the sun could be more sacred to him than where the relics of the Master lay? He would personally attend to all the items of worship; he would bring water from the Ganga, gather flowers, and prepare the food to be offered. He would not take any food that was not offered to the Master. The very soul of devotion entered into Swami Ramakrishnananda.

If Shashi’s devotion to the guru was beyond comparison with any earthly example, his love for Swamiji whom Sri Ramakrishna had ordained as the leader of the whole group, was wonderful. Any word from the leader was more than a command to him. There was no trouble which he would not face, no sacrifice which he would not make in deference to the slightest wish of Swami Vivekananda. This spirit was so strongly manifest in him, that Swami Vivekananda would at times make fun with him, taking advantage of his love. Shashi, as we have seen, was very orthodox in his attitude. One day the leader asked him, ‘Shashi, I want to put your love for me to the test. Can you buy me a piece of English bread from a Mohammedan shop?’ Shashi at once agreed and actually did the thing. After Swamiji’s return from the West when he proposed to Shashi to go to Madras to do preaching work, Shashi at once responded to the call. It meant that he would have to give up many habits of long years, it meant that he would have to leave the place where he was so steadfastly worshipping the relics of the Master. But these were no considerations against the wish of the leader.

After the Master had discouraged his book-learning, Shashi lost all interest in study. His whole heart was centred in devotion and worship. Now he was asked to preach religion and philosophy. The great heart had to become the mighty intellect. It may be that for this reason the leader directed Swami Ramakrishnananda to go to Madras. A combination of deep devotion and keen intellect is something very rare. But this very rare type was needed for the work in South India, and it was the good fortune of that province to get such an apostle.

The Ramakrishna Mission work in the South now stands as a noble edifice giving shelter to thousands of persons who seek the consolation which religion alone can give. But the strong foundation for this imposing edifice was firmly laid by the great monk, the first apostle of the Ramakrishna Order to Madras.

In Madras

Swami Ramakrishnananda arrived at Madras in 1897. At first he was housed in a small building near the ‘Ice House,’ from where he had to shift to some rooms in the Ice House where Swamiji had lived after his return from the West. A little later when the house was auctioned away by the owner, the Swami had to stay in an outhouse of the same building at great personal inconvenience. When the Ice House was put to auction, the devotees very much wished that if possible some of their friends should purchase it, so that Swami Ramakrishnananda might not be inconvenienced and his work might go on smoothly. As the auction was proceeding, the Swami sat unconcerned in a far end of the compound on a rickety bench. A devotee was anxiously watching the bidding and now and then reporting to the Swami how it was progressing. The Swami looked up and said, ‘Why do you worry about it? What do we care who buys or sells? My wants are few. I need only a small room for Sri Guru Maharaj. I can stay anywhere and spend my time in talking of him.’ Indeed such was the attitude of the Swami throughout his whole life, even later when he received much ovation and many honours.

It was in 1907 that a permanent house1 for the Math was constructed on a small site in a suburb of the city. The house was a simple one-storeyed building consisting of four rooms, a spacious hall, kitchen, and outhouses. The Swami was delighted when at last there was a permanent place where the Master’s worship could be carried on uninterruptedly. He said, ‘This is a fine house for Sri Ramakrishna to live in. Realizing that he occupies it, we must keep it very clean and very pure. We should take care not to disfigure the walls by driving nails or otherwise.’

The worship of the Master as done by Swami Ramakrishnananda was very striking. A spiritual aspirant longs to experience the tangible presence of God. But with Swami Ramakrishnananda it was an entirely different matter. He so vividly realised the presence of God that there was no room for any craving for that in his mind. It was only left to him to serve Him, and he did it with unwavering ardour. He would serve his Master exactly in the way he did while he was in the physical body. Some article of food is preferred hot; Swami Ramakrishnananda would keep the stove burning and offer that piece by piece to the Master. He would offer to the Master a piece of twig hammered soft to be used as a toothbrush, as is the practice in some Indian homes. After the midday offerings, he would fan the Master for some time so that the latter could easily have his nap. On hot days he would suddenly wake up at night, open the shrine and fan the Master so that the latter might not be disturbed in sleep because of the sweltering heat. Sometimes he would talk sulkily with the Master, blaming him for something. To a critical mind these things might seem queer, but he only knew what great Presence he felt. These actions were so natural and spontaneous with him that a witness would sometimes even fall into respecting him for them. Once a certain gentleman, who was then holding the highest position in government service, called at the monastery to pay his respects to Swami Ramakrishnananda. The Swami, after finishing the morning worship, was at that time fanning the portrait of the Master, which he would do for a couple of hours and more, uttering the names of the Lord— Shiva Guru, Sat Guru, Sanatana Guru, Parama Guru, and so on. During such times, the face of the Swami would be flushed red with emotion and his tall and robust figure would look more imposing. The whole sight struck the visitor with such awe and reverence that he could do nothing but prostrate before the Swami and return home.

A bold student to whom the Swami gave the liberty of arguing, once freely criticized him for worshipping the portrait of a dead man as that indicated an aberration of mind. The Swami said that the images in temples were not simply dull, dead, inert matter, but were living gods who could be spoken to. There was such a ring of sincerity and genuineness of feeling behind these words that in spite of himself, the conviction stole on the critic, as he himself afterwards narrated, that what he heard could not but be true.

But if Swami Ramakrishnananda’s devotion was great, his intellectual acumen was no less so. His scholarship in Sanskrit was immense. Not knowing the local dialect, he had sometimes to hold conversations with orthodox pundits in Sanskrit. He wrote the life of the great Acharya Ramanuja in Bengali, which has become an authoritative book on that saint. Not only of Hindu scriptures, but his knowledge of Christianity and of Islam also was superb. He knew the Bible from cover to cover and could expound it with a penetrating insight which would strike even orthodox Christian theologians with awe. Once on a Good Friday he gave a talk on the Crucifixion with so much depth of feeling and vividness of description that a Western listener, with experience of sermons in churches, became amazed as to how the words of the Swami could be so living. Though to all intents and purposes he was living like an orthodox Hindu, his love for the prophets of other faiths was genuine and sometimes embarrassing to his orthodox followers. Those who have seen him going to St. Thomas’ Church in Madras relate that he would go straight up to the altar and kneel before it like a Christian and pray.

One evening some Mohammedan students, caught in the rain, took shelter in the monastery. The Swami warmly welcomed them and talked to them not of his own faith but of Islam. His exposition was so illuminating that those Mohammedan students repeated their visit to the monastery many times afterwards.

As a preacher and writer

When holding scripture classes or giving religious discourses, he would not simply explain the texts or repeat the scriptural authorities. He would at times give flashes of illumination from the depth of his realisations. Because of this, his words were always penetrating. They would silence even those who came with a combative spirit. With a few words he could explain philosophical problems on which volumes had been written. He had a great knack of probing into the heart of things and of expressing the truth in pithy sayings. Once after discussions with the professor of a local college in regard to politics and religion, the Swami said, ‘Politics is—the freedom of the senses, while religion is freedom from the senses.’ With reference to dualistic and monistic systems of philosophy he once remarked, ‘In the dualistic method enjoyment is the ideal; in the monistic method freedom is the ideal. By the first the lover gets his beloved at last, and by the second the slave becomes the master. Both are sublime. One has no need to go from one ideal to the other.’ ‘Science is the struggle of man in the outer world. Religion is the struggle of man in the inner world’, he once said in the course of conversation, ‘Both struggles are great, no doubt, but one ends in success and the other ends in failure. That is the difference. Religion begins where science ends.’

He had, however, no prejudice against science. At times he would be solving mathematical problems as a pastime. Once he procured from a local college all the latest authoritative books on astronomy and began to study them assiduously. It was not difficult for him to understand them.

Throughout his stay in Madras, the Swami had to work very hard and pass through strenuous days. In the early period he had to cook his own food, do service in the shrine, and hold classes in various parts of the city. Sometimes the financial trouble was appalling. But very few people outside his intimate group knew of his difficulties. He would often be very reluctant even to accept the help proffered, for he did not like that anybody should undergo any sacrifice for him. One day there was not a drop of ghee in the Math to fry chappati. He was in a fix and began pacing up and down the verandah, not knowing where help would come from. As a strange coincidence, a student of his class approached him exactly at that time and whispered into his ear about his intention of contributing his mite to the Math as he had a promotion in the office. But the Swami did not at first agree to accept anything from him, lest it should cause him some hardship. It was only after great insistence and supplication that the Swami agreed to have some quantity of ghee. If questioned as to how the Swami was meeting his bodily wants, he would say with placid composure, ‘God sends me whenever I want anything.’ ‘If we cannot get on altogether without help, then why not ask the Lord Himself? Why go to others?’ he would say. And on many occasions help would come to the Swami in quite unexpected ways. A devotee says, ‘Once the birthday of Sri Ramakrishna was near and no money had been received for the feeding of the poor, which was an important item of the celebration. It was midnight and I was sleeping in the Math, when I suddenly woke up, roused by strange sounds in the hall. Looking about, I could see the Swami pacing up and down like a lion in a cage, mumbling noisily with every breath. I was afraid to see him in that condition, but I understood later that it was his praying for help to feed the poor. The next morning money did come. A large donation was received from the Yuvaraja of Mysore who had begun to admire the Swami, having read his book The Universe and Man, just then published.’

Without caring for his bodily wants, quite indifferent to his personal needs, he worked tremendously to spread the message of the Master and in the cause of Vedanta. On certain days of the week he had to lecture more than twice or thrice. His classes were scattered over different parts of the city, and to many of them he had for a long time to go on foot. Sometimes he would return to the Math quite exhausted, and as little energy was left for cooking, he would finish his night meal with only a piece of bread purchased from a bakery. People would wonder how he could stand such a severe strain. But the secret of this lay perhaps in his complete self-surrender to the Lord. Once he said, ‘Suppose a pen were conscious; it could say, “I have written hundreds of letters”, but actually it has done nothing, for the one who holds it has written the letters. So, because we are conscious we think we are doing all these things, whereas in reality we are as much an instrument in the hands of a Higher Power as the pen is in our hands, and He makes all things possible.’

While holding classes or delivering lectures he never posed himself as a superior personage having a right to teach others. He considered himself always as a humble servant of the Lord. Sometimes on returning to the Math after delivering lectures, he would undergo some self-imposed punishment and earnestly pray to the Master that the lecture work might not give rise to any sense of egotism in him. Sometimes he had strange experiences in the classes, and he had a novel way of meeting them. After the first enthusiasm had died out, all his classes were not so well-attended. That depended also on what part of the city the class was held in. If, for any reason, not a single student happened to come to any of his classes, he would still give his discourse as usual in the empty room or spend in meditation the period fixed for the class. If asked the reason for these unusual actions, the Swami would reply, ‘I have not come here to teach others. This work is like a vow to me, and I am fulfilling it irrespective of whether anyone comes or does not come to my class.’

With regard to what he taught, he was uncompromising and fearless. Someone, finding him to hold high the ideals of renunciation and fearing lest some of the young listeners might be attracted to the ideal, suggested that certain devotees who were subscribing towards the maintenance of the Math might not like his teaching such things to the young people. On hearing these remarks, Swami Ramakrishnananda flared up and thundered forth, ‘What, am I to preach anything other than what I have learnt from my Master? If the Math cannot be financially maintained, I shall very gladly find accommodation in the verandah of one of my students’ houses.’

His work was not confined only to the city of Madras; but it spread throughout the Madras Presidency. One of the most important field of his activities was the Mysore State. When the name and influence of Swami Ramakrishnananda as a bearer of the message of the Master and Swamiji began to spread, the Vedanta Society of Ulsoor in Bangalore sent him an invitation in 1903 to deliver a course of lectures there. He accepted the invitation, and a splendid reception was accorded on his arrival. He stayed in Bangalore for three weeks. During this period he delivered about a dozen public lectures and held conversations morning and evening. His lectures were attended by a large number of eager and enthusiastic people, and his classes were also equally popular.

In the same year he carried the message of his Master to Mysore as well, where he delivered a series of five lectures. A noteworthy address was given in Sanskrit to the pundits of the place assembled in the local Sanskrit College. In this he rose to the height of his eloquence and clearly showed how the message of his Master harmonized the interpretations of the Vedanta by different Acharyas. It was very bold of him to do so, for the Sanskrit scholars of the South, strong champions of orthodoxy as they were, could hardly believe in anything outside the particular system of philosophy they followed.

The interest created by him in Bangalore was kept up by the Ulsoor Vedanta Society. In the following year he was again invited to Bangalore, this time to open a permanent centre. He delivered a series of lectures, opened some classes and left a junior Swami there to continue the work. In August 1906, he revisited Bangalore and Mysore with his brother disciple Swami Abhedananda, who had recently come from America. The two Swamis together delivered several lectures and consolidated the Vedanta work in Mysore State. During this visit the foundation stone of the Bangalore Ashrama was laid. After the building was constructed, Swami Brahmananda came on invitation to open it. Afterwards, Swami Ramakrishnananda would visit Bangalore whenever he could snatch away time from his busy life, and he directed the Ashrama and the Mission work in Bangalore and Mysore from Madras.

Swami Ramakrishnananda also visited Trivandrum and spent about a month there creating enthusiasm in the minds of the people. Besides, he made extensive tours to several parts of South India, and as a result of this, centres were started in several important places. His fame as a teacher of Vedanta spread far and wide. Even from such distant places as Burma and Bombay he received invitations. He visited those places and achieved great success.

Some of the discourses he delivered in various places have been published in book form. They now furnish spiritual sustenance to innumerable people who had not the opportunity to come into direct contact with him. Of these books The Universe and Man and The Soul of Man give lucid expositions of some of the fundamental principles of Vedanta. Sri Krishna, the Pastoral and Kingmaker, is as the title shows, the life of that great Divinity on earth and is a study of the hero as Godman.

Swami Ramakrishnananda was not a very eloquent speaker. There was no oratorical flourish in his speech. But his sincerity and thorough grasp of spiritual realities made his speeches very impressive. He was always at his best in the conversational method of teaching, which appealed directly to the heart owing to the sincerity with which it was uttered. Great truths, complicated questions, controversial problems, and all the heights and depths of ethics were discussed, but in the most simple manner possible, so that even a child might understand them.

As a Monk and Teacher

In day-to-day dealings Swami Ramakrishnananda was full of overflowing love. We have seen how at the Baranagore monastery he was ‘like a mother’ to all, taking extreme care of them. When any brother disciple of his came to the South on pilgrimage, he would be beside himself with joy, and did not know how sufficiently to take care of him. All feelings of Swami Ramakrishnananda welled forth, as it were, when Swami Brahmananda visited the South, and there was nothing he would not do for him. His attitude towards Swami Brahmananda was the logical outcome of his devotion to the Master. Because Sri Ramakrishna loved Swami Brahmananda so much, Swami Ramakrishnananda also treated him more with reverence than with brotherly love. It was a sight to see Swami Ramakrishnananda, with his bulky body, prostrate himself before his great brother disciple in all humility. A similar attitude in Swami Ramakrishnananda, though in a more intense degree, was in evidence, when the Holy Mother, with a party of women devotees, came to the South on pilgrimage. It is said that on this occasion he worked so hard to remove even the slightest inconvenience that might befall the party, that his health permanently broke down.

It was to his great loving heart that the Ramakrishna Mission Students’ Home in Madras owed its origin. At Coimbatore he once found that all the members of a family, except a few helpless children, had been swept away by plague. The pitiable condition of these poor children was too much for the loving heart of the Swami, so he took charge of them. This was the genesis of the educational activities of the Mission in the South, which have since expanded very greatly.

A teacher, he cared more for building up lives than for reaching a wide circle of indifferent auditors. He was a strict disciplinarian and insisted that all who came under his influence be perfect and exemplary in every detail of their conduct. Once a student was found sitting in his class with his chin resting on the palm of his hand. He at once said, ‘Do not sit like that, it is a pensive attitude. You should always cultivate a cheerful attitude.’ Sometimes thoughtless visitors to the Math would take out the daily paper and begin to read. The Swami would at once administer a mild rebuke saying, ‘Put away your paper. You can read that anywhere. When you come here, you should think of God.’ Once a proud and vainglorious pundit came to the Math and began to talk of his plans for reforming temples, society, and so on. Swami Ramakrishnananda listened to him quietly for some time and then opened his lips to remark, ‘I wonder what God did before you were born.’ The man at once became silent, and the conversation turned to healthier things. The man afterwards left the Math with a better attitude of mind. Once Swami Ramakrishnananda and an American devotee were putting up in the royal guest quarters at Bangalore as the guests of the Maharaja of Mysore. One day a member of the Maharaja’s official staff came to see them. The visitor began to detail some court gossip to the American devotee thinking that it would be a very entertaining topic of conversation. All the while that the conversation was going on, the Swami shifted his position in his chair again and again showing evident signs of great discomfort. When asked if he was feeling unwell, the Swami unsophisticatedly said, ‘I am all right, but I do not like your conversation.’ The visitor, however, took the rebuke without any offence and changed the subject of conversation.

Mahasamadhi

His own life was extremely disciplined. He was very regular and punctual in his habits. He would follow his self-imposed daily duties under any circumstances. As a rule, he began the day by reading the Gita and the Vishnu Sahasranama. Once the Swami passed the night outside the Math, to keep company with Swami Premananda, when the latter was on pilgrimage in the South. That night Swami Ramakrishnananda had not with him the Gita and the Vishnu Sahasranama. When he discovered this, he sent someone out to procure copies of those two books, so that he might not miss reading them next morning.

Though in managing the monastery he was a stern disciplinarian, at heart he was extremely soft and kind. Once when the time came for the departure of a junior Swami of the Order who had come to Madras, Swami Ramakrishnananda fed him well sitting by him and actually burst into tears when the latter was about to leave. Another time Swami Ramakrishnananda had gone to Bengal, and when he visited Calcutta, he learnt that a young brahmacharin of the Order who had for some time lived with him at Madras was lying ill at his parental home in the city. The Swami himself went to see the patient at his home. At this the brahmacharin was dumbfounded, that Swami Ramakrishnananda, who was held in such high esteem throughout the country, should come to his bedside. He could hardly believe his eyes.

It was his love for humanity that impelled him to work so hard in Madras. But after some time the body gave indications that it could no longer stand the stress of so much hard work. Yet the spirit was there. The Swami did not listen to the whisper of the flesh. In spite of his indifferent health, he carried on his hard labour till the body completely broke down, and the doctors diagnosed the disease as consumption. Word was sent to Calcutta, and his fellow monks there begged him to pass his last days with them. This he felt was best. He had thought of it, but not until the command came from the President of the Mission did he leave Madras. In Calcutta he was housed at the monastery in Baghbazar, and the most noted physicians visited him of their own accord. But his condition grew worse.

Most remarkable, however, was the strength of his spirit which burst forth in eloquent discourses concerning high spiritual matters, even whilst the body suffered most. One who loved him dearly, noticing him speak thus in this distressed state of body, asked him to desist. ‘Why?’ came the reply, ‘When I speak of the Lord, all pain leaves me, I forget the body.’ Even in delirium his mind and his voice were given to God. ‘Durga, Durga, Shiva, Shiva’, and the name of his Master were ever on his lips. His great esteem and his love for Christ, which was manifest throughout his lifetime, revived constantly in those days. Speaking of Jesus he would become eloquent. He would speak of how Sri Ramakrishna had regarded Christ and of how, when the Master had the vision of Christ during samadhi, the very body of the great founder of Christianity had entered into him. Swami Ramakrishnananda entered into Final Realisation on 21 August 1911.