Early Life

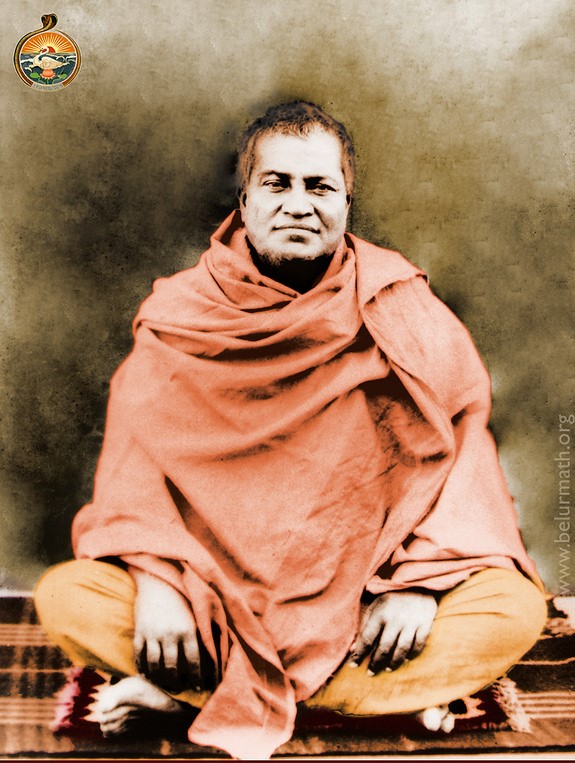

Swami Shivananda, more popularly known as Mahapurush Maharaj, was a personality of great force, rich in distinctive colour and individual quality. His leonine stature and dauntless vigour, his stolid indifference to praise or blame, his spontaneous moods and his profound serenity in times of storm and stress, invested with a singular appropriateness his monastic name which recalls the classical attributes of the great god Shiva.

He was born sometime in the fifties of the nineteenth century on the eleventh day of the dark fortnight in the Indian month of Agrahayana (November-December). The exact year of his birth is obscure. The Swami himself with his characteristic indifference to such matters never remembered it. His father had indeed prepared an elaborate horoscope for his son, but the latter threw it away into the Ganga when he chose the life of renunciation.

His early name, before he took orders, was Taraknath Ghosal. He came of a respectable and influential family of Barasat. One of his ancestors, Harakrishna Ghosal, was a Dewan of the Krishnanagar Raj. His father, Ramkanai Ghosal, was not only a successful lawyer with a substantial income but a noted Tantrika as well. Much of his earnings were spent in removing the wants of holy men and of poor helpless students. It was not unusual for him to provide board and lodging for twenty-five to thirty students at a time in his house. Later, when he became a deputy collector, his income fell, which forced him to limit his charities much against his wish. Subsequently, he rose to be the assistant Dewan of Cooch Behar.

We have already referred to Ramkanai Ghosal as a great Tantrika, and it will be interesting to recall here an incident which connected him with Sri Ramakrishna. For some time he was legal adviser to Rani Rasmani, the founder of the Kali temple of Dakshineshwar, where he came to be acquainted with Sri Ramakrishna during a visit on business matters. Sri Ramakrishna’s personality greatly attracted him, and whenever the latter came to Dakshineswar, he never missed seeing him. At one time, during intense spiritual practices, Sri Ramakrishna suffered from an acute burning sensation all over his body, which medicines failed to cure. One day he asked Ramkanai Ghosal if the latter could suggest a remedy. The latter recommended the wearing of his Ishtakavacha (an amulet containing the name of the Chosen Deity) on his arm. This instantly relieved him.

From his early boyhood Tarak showed unmistakable signs of what the future was to unfold. There was something in him which marked him out from his associates. It was not mere bold conduct and straightforward manners. Though a talented boy he showed very little interest in his studies. A vague longing gnawed at his heart and made him forget himself from time to time and be lost in flights of reverie. Early in life, he became drawn to meditative practices. As days passed, his mind gravitated more and more towards the vast inner world of spirit. Often in the midst of play and laughter and boyish merriment he would suddenly be seized by an austere and grave mood which filled his companions with awe and wonder. It is not surprising that his studies did not extend beyond school. Tarak, like scores of other young men, was drawn to the Brahmo Samaj, thanks to the influence of Keshab Chandra Sen. And though he continued his visits to the Samaj for some time, his hunger was hardly satisfied with what he got there.

Meanwhile his father’s earnings fell and Tarak had to look for a job. He went to Delhi. There he used to spend hours in discussing religious subjects in the house of a friend named Prasanna. One day he asked the latter about samadhi, to which Prasanna replied that samadhi was a very rare phenomenon which very few experienced, but that he knew at least one person who had certainly experienced it, and mentioned the name of Sri Ramakrishna. At last, Tarak heard about one who could teach him what he wanted to know. He waited patiently for the day when he would be able to meet Sri Ramakrishna.

With Sri Ramakrishna

Tarak continued his visits to Dakshineswar till the Master fell seriously ill in 1885, which necessitated his removal first to Calcutta and then to the Cossipore garden-house. All these years the Master had been quietly shaping the character of his disciples, instructing them not only in religious matters, but also in the everyday duties of life. Cossipore, however, formed the most decisive period in their lives.

Here Tarak joined the group of young brother disciples—Narendra, Rakhal, Baburam, Yogin, Niranjan, Sharat, Shashi, Latu, Kali, Gopal (senior) and Gopal (junior) to serve and attend on the Master during his illness. Service to the Master and loyalty to common ideals forged an indissoluble bond of unity among these young aspirants. Much of their time was devoted to discussion on religious subjects. All this set ablaze the great fire of renunciation smouldering in them, and they yearned for realisation.

One incident during this period is worth recounting. Narendra, Tarak, and Kali were at this time very much engaged in the thought of Buddha and of Brahman without any quality. Impelled by this they went for tapasya to Bodh Gaya. As they sat in meditation under the Bodhi tree, lost to outer consciousness, Narendra suddenly began to weep and then held Tarak in a warm embrace. According to one version, Narendranath, deep in the thought of Buddha’s compassion, was seized with such an emotional upsurge that he could not help embracing his brother out of overflowing love. Or perhaps, Narendra saw something of Buddha in Tarak. At least Kali affirmed that he heard from Narendra that the latter saw a light flash out of Buddha’s image and proceed towards Tarak. The Master too seems to have had a similar estimation of Tarak’s core of personality. About this estimation, we have it on the evidence of Swami Turiyananda that one day when Tarak was returning from the Kali temple, the Master remarked, ‘His “home” is that high Power from which proceed name and form.’ Tarak had something of the Transcendental Verity in him. And Buddha, it must be remembered, was not an atheist, but an embodiment of the Upanishadic ideal.

After the passing away of the Master, the small group of disciples clustered round the monastery of Baranagore. The first to come was Tarak, with whom soon joined Gopalda, Kali, and others. The Master’s death had created a great void in the hearts of the disciples, who began to spend most of their time in intense meditation in order to feel the living presence of the Master. Often they would leave the monastery and wander from place to place, away from crowded localities and familiar faces. This period of their lives, which stretched over a number of years and which was packed with severe austerities and great miracles of faith, out of the mighty fire of which was forged the powerful characters the world later saw, is mostly a sealed book. Towards the end of his life, Swami Shivananda, the name received by Tarak when he became a monk, one day chanced to lift a corner of the pall of mystery which lay over these stormy years. ‘Often it happened’, he said, ‘that I had only one piece of cloth to cover myself with. I used to wear half of it and wrap the other half round the upper part of my body. In those days of wandering I would often bathe in the water of wells, and then I used to wear a piece of loincloth and let my only piece of cloth dry. Many a night I slept under trees. At that time the spirit of renunciation was aflame and the idea of bodily comfort never entered the mind. Though I travelled mostly without means, thanks to the grace of the Lord, I never fell into danger. The Master’s living presence used to protect me always. Often I did not know where the next meal would come from. … At that period a deep dissatisfaction gnawed within, and the heart yearned for God. The company of men repelled me. I used to avoid roads generally used. At the approach of night I would find some suitable place just to lay my head on and pass the night alone with my thoughts.’

Some indication of Tarak’s bent of mind at this period can be had from a few reminiscences which have come down to us. He had a natural slant towards the orthodox and austere path of knowledge which placed little value on popular religious attitudes. He avoided ceremonious observances and disregarded emotional approaches to religion. He keyed up his mind to the formless aspect of the Divine. This stern devotion to jnana continued for some time. Deep down in his heart, however, lay his boundless love for the Master which nothing could affect for a moment. In later years, with the broadening of experience, his heart opened to the infinite beauties of spiritual emotion.

Last days with Sri Ramakrishna

Then came the period of supreme depression. The boys who were children of the Master gathered together at the newly founded monastery at Baranagore. Shashi played no small part in holding the young band together and in regulating the routine of life to be followed by them. While others were indifferent as to whether the body lived or died in their intense search for the Highest, Shashi took care that his brother disciples had not to face actual starvation. He went so far as to serve as a schoolmaster—though for a very short period—to meet the expenses of the Math. He would say to his brothers, ‘You just continue your spiritual practices with undivided attention. You need not bother about anything else. I shall maintain the Math by begging.’ Swamiji, recalling these blessed days many years later, said with reference to Swami Ramakrishnananda, ‘Oh, what a steadfastness to the ideal did we ever find in Shashi! He was a mother to us. It was he who managed about our food. We used to get up at three o’clock in the morning. Then all of us, some after bathing, would go to the worship room and be lost in japa and meditation. There were times when the meditation lasted to four or five o’clock in the afternoon. Shashi would be waiting with our dinner; if necessary, he would by sheer force drag us out of our meditation. Who cared then if the world existed or not!’

The parents of the boys came and attempted to take them back to their homes, but they would not yield. Shashi’s father came, begged and threatened, but to no purpose. The son said, ‘The world and home are to me as a place infested with tigers.’ The time came when the boys decided to renounce the world formally by taking the monastic vows. They changed their names. Shashi became Ramakrishnananda. Narendranath, the leader of the young band, wanted to have that name for himself but thought that Shashi had a better claim to it because of his unparalleled love for the Master. Indeed Shashi’s love for the Master sounds like a story, nay, has passed into stories. Death could not rob him of the living presence of the Master. He served the Master in the relics with the same devotion and earnestness as when he had been physically alive. Others went on pilgrimages, adopting the wandering life of the monk. Swami Ramakrishnananda stuck like a sentinel on to the holy spot where the Master’s relics were temporarily enshrined. Worshipping the Master and keeping the monastery as the centre to which the wanderers would occasionally return were the duties which Ramakrishnananda assigned to himself. He did not think of going to a single place of pilgrimage. What place under the sun could be more sacred to him than where the relics of the Master lay? He would personally attend to all the items of worship; he would bring water from the Ganga, gather flowers, and prepare the food to be offered. He would not take any food that was not offered to the Master. The very soul of devotion entered into Swami Ramakrishnananda.

If Shashi’s devotion to the guru was beyond comparison with any earthly example, his love for Swamiji whom Sri Ramakrishna had ordained as the leader of the whole group, was wonderful. Any word from the leader was more than a command to him. There was no trouble which he would not face, no sacrifice which he would not make in deference to the slightest wish of Swami Vivekananda. This spirit was so strongly manifest in him, that Swami Vivekananda would at times make fun with him, taking advantage of his love. Shashi, as we have seen, was very orthodox in his attitude. One day the leader asked him, ‘Shashi, I want to put your love for me to the test. Can you buy me a piece of English bread from a Mohammedan shop?’ Shashi at once agreed and actually did the thing. After Swamiji’s return from the West when he proposed to Shashi to go to Madras to do preaching work, Shashi at once responded to the call. It meant that he would have to give up many habits of long years, it meant that he would have to leave the place where he was so steadfastly worshipping the relics of the Master. But these were no considerations against the wish of the leader.

After the Master had discouraged his book-learning, Shashi lost all interest in study. His whole heart was centred in devotion and worship. Now he was asked to preach religion and philosophy. The great heart had to become the mighty intellect. It may be that for this reason the leader directed Swami Ramakrishnananda to go to Madras. A combination of deep devotion and keen intellect is something very rare. But this very rare type was needed for the work in South India, and it was the good fortune of that province to get such an apostle.

The Ramakrishna Mission work in the South now stands as a noble edifice giving shelter to thousands of persons who seek the consolation which religion alone can give. But the strong foundation for this imposing edifice was firmly laid by the great monk, the first apostle of the Ramakrishna Order to Madras.

Austerity and Pilgrimages

During his days of itineracy Swami Shivananda, known as Mahapurushji popularly among his disciples, visited various places in North India. In the course of these travels he also went to Almora where he became acquainted with a rich man of the place named Lala Badrilal Shah, who soon became a great admirer of the disciples of Sri Ramakrishna and took great care of them whenever he happened to meet them. Here, towards the later part of 1893, the year of Swamiji’s journey to the West, Tarak met Mr E T Sturdy, an Englishman interested in Theosophy. Mahapurushji’s personality and talks greatly attracted him. Mr Sturdy came to hear of Swamiji’s activities in the West from him, and on his return to England he invited Swamiji there and made arrangements for the preaching of Vedanta in England.

With the return of Swamiji from the West in 1897, Mahapurushji’s days of itineracy came to an end. He went to Madura to receive Swamiji, and returned with him to Calcutta. In the same year, at the request of Swamiji, he went to Ceylon and preached Vedanta for about eight months. There he used to hold classes on the Gita, and the Raja Yoga, which became popular with the local educated community including a number of Europeans. One of his students, Mrs Picket, to whom he gave the name Haripriya, was specially trained by him so as to qualify her to teach Vedanta to the Europeans. She later went to Australia and New Zealand at the direction of the Swami and succeeded in attracting interested students in both the countries. He returned to the Math in 1898, which was then housed at Nilambar Babu’s garden.

In 1899 plague broke out in an epidemic form in Calcutta. Swami Vivekananda asked Swami Shivananda and others to organise relief work for the sick. The latter put forth his best efforts without the least thought for his personal safety. About this time a landslide did considerable damage to property at Darjeeling, and Mahapurushji also collected some money for helping those who were affected by it.

The natural drive of his mind was, however, for a life of contemplation, and so he went again to the Himalayas to taste once more the delight and peace of meditation. Here he spent some years, although he would occasionally come down to the Math for a visit. About this time Swamiji asked him to found a monastery in the Himalayas. Although this desire could not be realised at the time, Swami Shivananda remembered his wish and years afterwards, in 1915, he laid the beginnings of a monastery at Almora, which was completed by Swami Turiyananda with his cooperation.

In 1900 he accompanied Swami Vivekananda on the latter’s visit to Mayavati. While returning to the plains Swamiji left him at Pilibhit with a request that he should collect funds for the maintenance and improvement of the Belur Math. He stayed back and raised some money.

Shortly before Swamiji passed away, the Raja of Bhinga gave him Rs 500 for preaching Vedanta. Swamiji handed the money over to Swami Shivananda asking him to start an Ashrama with it at Varanasi, which he did in 1902.

At Varanasi

The seven long years which he spend at this Varanasi Ashrama formed a memorable chapter of his life. Outwardly, of course, there was no spectacular achievement. The Ashrama grew up, not so much as a centre of great social activity, but as a school of hard discipline and rigorous tapasya for the development of individual character as in the hermitages of old. Here we are confronted with an almost insurmountable obstacle in the way of presenting the life-story of spiritual geniuses. The most active period of their lives is devoid of events in popular estimation. It is hidden away from the public eye and spent in producing those invisible and intangible commodities whose value cannot be measured in terms of material goods. When they appear again, they are centres of great and silent forces which often leave their imprint on centuries. Realisation of God is not an event in the sense in which the discovery of a star or an element is an event, which resounds through all the continents. But one who has solved the riddle of life is a far greater benefactor of humanity than, say, the discoverer of high scientific truths.

Anxious times were ahead for Swami Shivananda; the funds of the Varanasi Ashrama were soon depleted. At times nobody knew wherefrom the expenses of the day would come. Mahapurushji, however, carried on unruffled and the clouds lifted after a while. Most of his time was spent in intense spiritual practices. He would scarcely stir out of the Ashrama, and day and night he would be in a high spiritual mood. The life in the Ashrama was one of severe discipline and hardship. The inmates hardly enjoyed full meals for months, and there was not much clothing to lessen the severity of the winter. He himself used to pass most of the nights on a small bench. In the winter months he would usually get up at about three in the morning and light a Dhuni fire in one of the rooms, before which they would sit for meditation, which often continued far into the morning. During these times Swami Saradananda, the then Secretary of the Mission, would press him hard to try to collect funds for the local Home of Service and would say jocosely, ‘Will mere meditation bring money?’ But the Swami could not be moved from the tenor of his life.

For some time he opened a school at the Ashrama, where he himself taught English to a group of local boys. About this time he translated Swami Vivekananda’s Chicago lectures into Hindustani so that Swamiji’s ideas might spread among the people. He continued to look after the affairs of the Ashrama till 1909, when he returned to Belur and lived there for some time. In 1910 he went on a pilgrimage to Amarnath in the company of Swami Turiyananda and Swami Premananda. On his return he fell seriously ill with dysentery, which proved very obstinate. He became specially careful as regards food after this and began to observe a strict regimen, which continued till the end and to which his long life was in no small measure due.

In Belur Math and other places

In 1910 he was elected Vice President of the Ramakrishna Mission. In 1917 Swami Premananda who used to manage the affairs of the Math at Belur fell seriously ill, and his duties came to rest on the shoulders of Swami Shivananda. And in 1922, after the passing away of Swami Brahmananda, he was made the President of the Ramakrishna Math and Mission, in which post he continued till the end of his life. Shortly before this, he had been to Dacca and Mymensingh in response to an invitation. This tour started a new phase in his long career which has left a very profound impression upon all who came in contact with him during this period. Large crowds flocked to him at places in Dacca and Mymensingh to hear him talk on spiritual matters, and for the first time he began to initiate persons into spiritual life at the earnest appeal of several devotees, though at first he was much against it.

In 1924 and 1927 he went on two long tours to the South, during which he formally opened the centres at Bombay, Nagpur, and Ootacamund and initiated a large number of persons into religious life. The hill station of Ootacamund appealed to him greatly, and here he spent some time in a high spiritual mood. In 1925 during the winter he went to Deoghar accompanied by a large number of monks from the Belur Math to open the first buildings of the local Ramakrishna Mission. He stayed there for a little over three weeks which was a period of unalloyed joy and bliss for all who happened to be there. Wherever he went he carried an atmosphere of delight around him. Monks and devotees thronged round him morning and evening, and for hours the conversations on spiritual subjects continued. Two incidents at Deoghar and Ootacamund are worth recounting here.

During his stay at Deoghar, he had a severe attack of asthma, which compelled him to spend the night in a sitting posture. As the suffering was intense and he felt like dying, he concentrated his mind on the Indwelling Self and became immediately oblivious of pain. When relating the incident the next day, he said, ‘As it was the meditation of a mature age, the mind soon dived inward’, and he pointed to his chest. ‘What is that, sir?’ inquired a listener. ‘That indeed is the Self ‘, replied the Swami. The Ootacamund hills had a spiritual tranquillity which easily lifted his mind to a higher level of experience. As he sat one day looking out at the blue hills spreading in front like the waves of a sea, he felt as though something emerged out of his body, spread all over the landscape, and became identified with all that existed. Did he realise God there in His cosmic form (Virat)?

After 1930 his health broke down greatly, though he could still take short walks. What a cataract of disasters had come upon him since 1927—loss of the comrades of old days one after another, trouble and defections, illness and physical disabilities! But nothing could for a moment dim the brightness of his burning flame of reliance on God. They only brought into high relief the greatness of his spiritual qualities. At night, after meals, he would usually pass an hour or so all alone, except for the presence of an attendant or two who used to be near. And whenever he was alone he seemed to be immersed in a profound spiritual mood. He would occasionally break the silence by gently uttering the Master’s name. The mood would recur whenever in the midst of an almost uninterrupted flow of visitors and devotees he found a little time to himself. In the midst of terrible physical suffering he would radiate joy and peace all round. Not once did anyone hear him utter a syllable of complaint against the torments which assailed the flesh. To all inquiries about his health his favourite reply was, ‘Janaki (Sita) is all right so long she is able to take the name of Rama.’ Physicians who came to treat him were amazed at his buoyant spirits which nothing could depress. Sometimes he would point to his pet dog and say, ‘That fellow’s master is here (pointing to himself)’, and then pointing one finger to himself and another to the Master’s shrine he would add, ‘and this fellow is His dog.’

Age, which diminishes our physical and mental vigour, serves only to heighten the force and charm of a spiritual personality. The last years of Swami Shivananda’s life were days of the real majesty of a spiritual sovereign. The assumption of the vast spiritual responsibilities of the great office tore off the austere mask of reserve and rugged taciturnity which so long hid his tender heart and broad sympathy. All these years thousands upon thousands came to him, men and women, young and old, rich and poor, high and low, the homeless and the outcast, men battered by fate and reeling under the thousand and one miseries to which man is prey, and went back lifted up in spirits. A kind look, a cheering word, and an impalpable something which was nevertheless most real, put new hope and energy into persons whose lives had almost been blasted away by frustrations and despair. He cheerfully bore all discomfort and hardship in the service of the helpless and the needy. Even during the last illness which deprived him of the power of speech and half of his limbs, the same anxiety to be of help to all was plain, and his kindly look and the gentle movement of his left hand in blessing, and, above all, his holy presence did more to brace up their drooping spirits than countless words contained in books could ever do.

During his term of office, the work of the Mission steadily expanded. The ideas of the Master spread to new lands, and centres were opened not only in different parts of India, but also in various foreign countries. He was, however, no sectarian with limited sympathy. All kinds of work, social, national, or religious, received his blessings. Labourers in different fields came to him and went away heartened by words of cheer and sympathy. His love was too broad to be limited by sectional interests; it extended to every place and to every movement where good was being done. Are not all who toil for freedom and justice, for moral and religious values, for the removal of human want and suffering, for raising the material and cultural level of the masses, doing the Master’s works? He was no mere recluse living away from human interests and aspirations, away from the currents of everyday life. His was an essentially modern mind keenly aware of the suffering of the poor and downtrodden. His clear reason unaffected by sectional interests could grasp the truth behind all movements for making the lot of the common man happy and cheerful. When the Madras Council was considering the Religious Endowment Bill which aimed at a better management of the finance of the religious Maths, the abbot of a Math in Madras approached him seeking his help for fighting the measure because it touched the vested interests. But the Swami told him point-blank that a monastery should not simply hoard money, but should see that it comes to the use of society. When news of flood and famine reached him, he became anxious for the helpless victims and would not rest till relief had been organised.

One day he was invited for meal at a devotee’s house in Madras. When resting after food he was roused by some noise downstairs, and looking through the window he found some poor people gathering together the food in the leaves thrown down after the guests had been satisfied. Being much moved by the sight, the Swami asked the devotee to feed them properly, and he remarked, ‘India has no hope till she atones for this accumulated sin.’ Mahapurushji naturally avoided politics. But he was full of admiration for the spirit of renunciation and service that inspired some of the outstanding patriots. About Mahatma Gandhi, for instance, he said, ‘The patriotism of Swamiji has taken possession of Gandhiji. All should imitate Gandhi’s character. There will be some hope of peace only when such people are born in every country.’

Full of praise though he was of the heroic efforts of the Mahatma and his followers, Mahapurushji never for a moment deviated from the path of spirituality chalked out by Swamiji. Thus when in the heyday of Mahatmaji’s non-cooperation movement, some Bengali leaders felt that the Ramakrishna Mission should take an active part in politics, that being according to them the inner core of Swamiji’s teachings, and when, under such an impression, some people warned Mahapurushji that the Mission was inviting disaster by thus standing aloof from the national movement, Mahapurushji calmly told them that the path of national salvation lay through the formation of character on a spiritual basis. That was the real message of Swamiji. Others might follow the path they considered best, but the Mission could not give up its ideals for gaining any temporary advantage. In fact he spoke as a true son of the Master was expected to speak.

Though all kinds of good work found him sympathetic, he never failed to stress the spirit which should be at the back of all activities. One who witnesses the drama of life from the summit of realisation views its acts in a light denied to common understanding. Our toils and strivings, our joys and delights, our woes and tears are seen in their true proportion from the vast perspective of the Eternal. Work yoked to true understanding is a means for the unfoldment of the divine within man. So his advice was always: Behind work there should be meditation; without meditation, work cannot be performed in a way which is conducive to spiritual growth. Nor is work nicely performed without having a spiritual background. He would say, ‘Fill your mind in the morning so much with the thoughts of God that one point of the compass of your mind will always be towards God though you are engaged in various distracting activities.’

His own life was a commentary on what he preached. Though he soared on the heights of spiritual wisdom he was to the last rigid in attending to the customary devotions for which he had scarcely any need for himself. Until the time he was too weak to go out of his room, every dawn found him in the shrine room meditating at a fixed hour. In the evening, perhaps, he would be talking to a group of people when the bell for evening service rang. He would at once become silent and lost in deep contemplation, while those who sat round him found their minds stilled and they enjoyed a state of tranquillity which comes only from deep meditation.

Not only did his life stand out as the fulfilment of the ideal aspirations of the devotee, as an ever-present source of inspiration, but his kindness and pity issued forth in a thousand channels to the afflicted and the destitute. Not all who came to him were in urgent need of spiritual comfort. Empty stomachs and naked bodies made them far more conscious of their physical wants than of the higher needs of the soul. His charities flowed in a steady stream to scores of persons groaning under poverty. Perhaps there came to him one whose daughter had fallen seriously ill, but who did not know how to provide the expenses for her treatment. There was another who had lost his job and stared helplessly at the future. Such petitions and their fulfilment were an almost regular occurrence during his last years, not to mention his constant gifts of cloths and blankets, and so on, to hundreds of people.

His love for the Master, his monastery, and his devotees knew no bounds. His doors remained ever open to the monks and devotees, and so long as it was physically possible for him, he moved about the monastery grounds looking after everything and inquiring about everybody. The cowshed, the kitchen, the dispensary, in fact everything belonging to the Master got his fullest attention. His special care was of course for the shrine room. Everyday he inquired about the offerings to be made to Sri Ramakrishna. When any devotee brought fruits or flowers for himself, he insisted on those being first offered to the Master. The first duty for anyone entering the monastery was to offer his salutation at the shrine.

In the days of his physical decline, the grand old man, whom illness had confined to bed, was like a great patriarch, a paterfamilias, affectionately watching over the welfare of his vast brood. His love showed itself in a hundred ways. If anyone of his numerous devotees or members of the monastery fell sick, he never failed to make anxious inquiries about him. If any of the devotees did not turn up on the usual days at the Math, it never failed to attract his notice. And when the devotees came to the Math, even their petty needs and comforts engaged his attention. But very few of them came to know of this.

His numerous children, who felt secure in his affectionate care, went about their duties full of the delight of living. One night, after the meal, some of the members of the monastery at Belur were making fun and laughing loudly in the inner verandah of the ground floor of the main Math building. The noise of laughter rose up and could be heard in Mahapurushji’s room. He smiled a little at this and said softly: ‘The boys are laughing much and seem to be happy. They have left their hearth and home in search of bliss. Master! Make them blissful.’ What an amount of feeling lay behind these few tender words of prayer!

Mahasamadhi

His health, which was already shattered, broke down still more and beyond recovery in April 1933, when he had an attack of apoplexy, which deprived him of the use of half of his body including speech. He passed away on 20 February 1934, leaving a memory which is like a golden dream flung suddenly from one knows not where into this harsh world of reality.

The real is that which is an object of experience. To Swami Shivananda God and religion were not vague words or distant ideals, but living realities. Lives like his light up the dark recesses of history and point to the divine goal towards which humanity is travelling with growing knowledge.