Early Life

The early name of Swami Subodhananda was Subodh Chandra Ghosh. He was born in Calcutta on 8 November 1867 and belonged to the family of Shankar Ghosh, who owned the famous Kali temple at Kalitala (Thanthania), Calcutta. His father was a very pious man and fond of religious books; his mother also was of a very religious disposition. The influence of his parents contributed not a little to the growth of his religious life. His mother would tell him stories from the Ramayana, the Mahabharata, and other scriptures, and implanted in him, while still very young, love for truth and devotion to God. From his very boyhood, he showed a remarkable spirit of renunciation and had a vague feeling that he was not meant for a householder’s life. When pressed to marry, he emphatically said that he would take to the life of a wandering monk, and so the marriage would only be an obstacle in his path. As it was settled that on his passing the class eight examination, he was to be married, Subodh fervently prayed to God that the result of his examination might be bad. God heard the prayer of the little boy, and Subodh, to his great relief, failed in the examination and did not get the promotion. Subodh was at first a student of the Hare School and was then admitted into the school founded by Pundit Ishwar Chandra Vidyasagar.

At this time he got from his father a copy of the Bengali book, The Teachings of Sri Ramakrishna by Suresh Chandra Datta. He was so much impressed with its contents that he became very eager to see Sri Ramakrishna. His father told him to wait until some holiday when he could conveniently take him to Dakshineswar. But Subodh was impatient of any delay.

With Sri Ramakrishna

So one day in the middle of 1885, he stole away from the house and along with a friend started on foot for Dakshineswar. There he was received very affectionately by the Master, who caught hold of his hand and made him sit on his bed. Subodh felt reluctant to sit on the bed of a holy person, but the Master disarmed all his fears by treating him as if he were his close relation. In the course of the conversation, he told Subodh that he knew his parents and had visited their house occasionally and that he had also known that Subodh would be coming to him. He grasped the hand of Subodh and remaining in meditation for a few minutes said, ‘You will realise the goal, Mother says so.’ He also told Subodh that the Mother sent to him those who would receive Her grace, and asked the boy to visit him on Tuesdays and Saturdays. This was difficult of accomplishment for Subodh, as great objection would come from his parents if they knew of his intention.

The next Saturday, however, Subodh fled away from the school with his friend and went to Dakshineswar. During this visit Sri Ramakrishna in an ecstatic mood stroked his body from the navel to the throat and wrote something on his tongue, repeating, ‘Awake, Mother, awake!’ Then he asked Subodh to meditate. As soon as he began meditation his whole body trembled and he felt something rushing along the spinal column to his brain. He was plunged into a joy ineffable and saw a strange light in which the forms of innumerable gods and goddesses appeared and then got merged in the Infinite. The meditation gradually deepened, and he lost all outward consciousness. When he came down to the normal plane, he found the Master stroking his body in the reverse order. Sri Ramakrishna was delighted to see the deep meditation of Subodh, and learnt from him that it was the result of his practice at home for; Subodh used to think of the gods and goddesses of whom he heard from his mother.

After that meeting with the Master, Subodh would see a strange light between his eyebrows. His mother, coming to know of this, told him not to divulge this fact to anybody else. But seized as he was with a great spiritual hankering, Subodh promptly replied, ‘What harm will it do to me, mother? I do not want this light but That from which it comes.’

From his very boyhood, Subodh was very frank, open-minded, and straightforward in his talk. These characteristics could be seen in him throughout his life. What he felt, he would say clearly without mincing matters. One day the Master asked Subodh, ‘What do you think of me?’ The boy unhesitatingly replied, ‘Many persons say many things about you. I won’t believe in them unless I myself find clear proofs.’ As he began to come closer and closer in touch with Sri Ramakrishna, the conviction gradually dawned on him that the Master was a great Saviour. So when one day the Master asked Subodh to practise meditation, he replied, ‘I won’t be able to do that. If I am to do it why did I come to you? I had better go to some other guru.’ Sri Ramakrishna understood the depth of the feeling of the boy and simply smiled. But this did not mean that Subodh did not like to meditate—his whole life was one of great austerity, prayer, and steadfast devotion—it only indicated his great confidence in the spiritual powers of the Master.

Subodh’s straightforward way of talking led to a very interesting incident. One day the Master asked Subodh to go now and then to Mahendranath Gupta—afterwards known as ‘M’—who lived near Subodh’s home in Calcutta.

At this, the boy said, ‘He has not been able to cut asunder his family tie, what shall I learn of God from him?’ The Master enjoyed these words indicative of Subodh’s great spirit of renunciation and said, ‘He will not talk anything of his own. He will talk only of what he learns from here.’ So one day Subodh went to ‘M’ and frankly narrated the conversation he had had with the Master. ‘M’ appreciated the frankness of the boy and said, ‘I am an insignificant person. But I live by the side of an ocean, and I keep with me a few pitchers of sea water. When a visitor comes, I entertain him with that. What else can I speak?’ The sweet and candid nature of Subodh soon made him a great favourite with ‘M’. After this Subodh was a frequent visitor at his house, where he would often spend long hours listening to M’s talks on the Master.

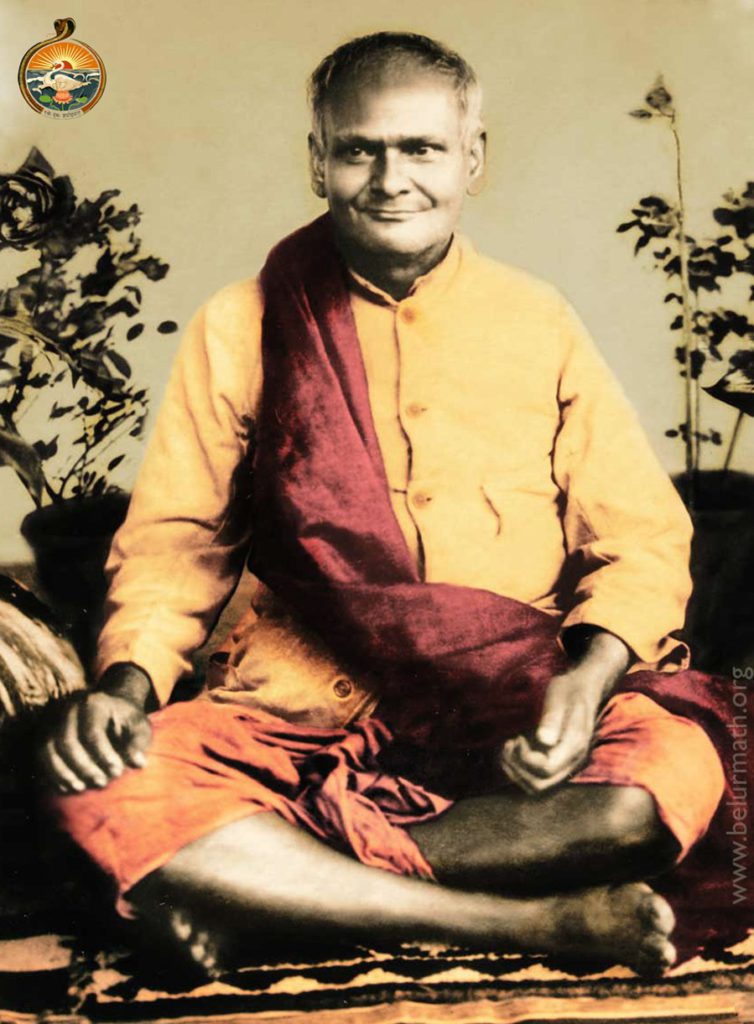

After passing away of the Master

Gradually the attraction of young Subodh for the Master grew stronger and stronger, and some time after the passing away of the Master, he left his parental homestead and joined the monastic Order organized by Swami Vivekananda at Baranagore. His monastic name was Swami Subodhananda. But because he was young in age and simple in nature, Swami Vivekananda would lovingly call him ‘Khoka’, meaning child, by which name he was also called by his brother disciples. He was afterwards known as ‘Khoka Maharaj’ (Child Swami).

Towards the end of 1889, along with Swami Brahmananda, Swami Subodhananda went to Varanasi and practised tapasya for a few months. In 1890 they both went on a pilgrimage to Omkar, Girnar, Mount Abu, Bombay, and Dwaraka and after that went to Vrindavan, where they stayed for some time. He also underwent spiritual practices in different places in the Himalayan region, later went to the holy shrines of Kedarnath and Badrinarayan twice and also visited the various holy places in South India, going as far as Cape Comorin. He also went afterwards on a pilgrimage to Assam.

Famine relief

When Swamiji, after his return from the West, appealed to his brother disciples to work for the spread of the Master’s message and the good of humanity instead of living in seclusion, Subodhananda was one of those who placed themselves under his lead. After that he worked in various capacities for the cause of the Ramakrishna Math and Mission. During the great epidemic of plague in Calcutta in 1899, when the Ramakrishna Mission plague service was instituted, Swami Subodhananda was one of those who worked hard for the relief of the helpless and panic-stricken people.

During the great famine on the Chilka islands in Orissa in 1908, he threw himself heart and soul into the relief work. He had a very tender heart. The sight of distress and suffering always found an echo in him. He would often be found near sick-beds nursing the sick at considerable risk to his own health. On one occasion he nursed a young student suffering from smallpox of a very malignant type with such loving care and attention that it amazed all who witnessed it. Sometimes he would beg money from others in order to help poor patients with diet and medicine. Many poor families did he help with money given by devotees for his personal needs. One family near the Belur Math was saved from actual starvation by the kindness of the Swami. If he knew that a devotee was ill, he was sure to go to see him. The devotee would be surprised and overwhelmed with emotion at this unexpected stroke of kindness on the part of the Swami. A young member of the Alambazar Math had to go back temporarily to his parents because of illness. Swami Subodhananda would now and then call on him and inquire about his health. That young member rejoined the monastery after his recovery, and he remembered for ever with respectful gratitude the kindness he received in his young age from Swami Subodhananda.

Later, although Swami Subodhananda could not personally work so much, wherever he would be, he would inspire people to throw themselves into the work started by Swamiji. During his last few years, he made extensive tours in Bengal and Bihar and was instrumental in spreading the message of the Master. He would even go to the outlying parts of Bengal, scorning all physical discomfort and inconvenience.

Spiritual Ministration

In imparting spiritual instructions also, he spent himself without any reserve. During his tours, he had to undergo great inconvenience and to work very hard. From morning till late at night, with little time left for personal rest, he had to meet people and talk of religious things—about the message of the Master and Swami Vivekananda. But never was his face ruffled and nobody could guess that there was one who was passing through great hardship. The joy of giving was always on his face. The number of persons who got spiritual initiation from him was very large. He even initiated some children. He would say, ‘They will feel the efficacy when they grow up.’ But in this act of spiritual ministration there was not the least trace of pride or self-consciousness in him. If people would approach him for initiation, he would very often say, ‘What do I know? I am a Khoka.’ He would refer them to the more senior Swamis of the Order. Only when they could not afford to go to them, did he grant their prayer. In accepting the supplicants as disciples, he made no distinction between the high and the low. He initiated many who were considered untouchable by the society. His affection for them was not a whit less than that for those disciples who held good positions in society or were more fortunately placed in life.

Swami Subodhananda was one of the first group of trustees of the Belur Math appointed by Swamiji in 1901, and was afterwards elected Treasurer of the Ramakrishna Mission. His love for Swamiji was next to that for the Master. Swamiji also had great affection for him. Sometimes when Swamiji would become serious and none of his gurubhais dared approach him, it was left to ‘Khoka’ to go and break his seriousness.

Childlike Deportment

Swami Subodhananda was childlike in his simplicity and singularly unassuming in his behaviour. It is said in the Bible, ‘Except ye be converted, and become as little children, ye shall not enter into the kingdom of heaven.’ But rare are the persons who can combine in their lives the unsophisticated simplicity of a child with the high wisdom of a sage. One could see this wonderful combination in Swami Subodhananda. Swami Vivekananda and other brother disciples greatly loved the childlike aspect of the personality of Swami Subodhananda. But they would not therefore fail to make fun now and then at his cost, taking advantage of his innocence and unsophisticated mind. Once, while the monastery was at Alambazar, Swami Vivekananda wanted to encourage the art of public speaking among the monks. It was arranged that every week on a fixed day one of them should speak. When the turn of Swami Subodhananda came, he tried his best to avoid the meeting. But Swamiji was adamant, and others were waiting with eagerness to witness the discomfiture of Subodh while lecturing. Just as Swami Subodhananda rose to speak, lo! the earth trembled, buildings shook and trees fell—it was the earthquake of 1897. The meeting came to an abrupt end. The young Swami escaped the ordeal of lecturing but not the fun at his cost. ‘Khoka was a “world-shaking” speech’, Swamiji said, and others joined in the joke.

Swami Vivekananda was once greatly pleased with ‘Khoka’ for some personal services rendered by him and said that whatever boon he would ask of him would be granted. Swami Subodhananda said, ‘Grant me this— that I may never miss my morning cup of tea.’ This threw the great Swami into a roar of laughter, and he said, ‘Yes, it is granted.’ Swami Subodhananda had his morning cup of tea till the last day of his life. It was the only luxury for which he had any attraction. It was like a child’s love for chocolates and lozenges. It is interesting to record in this connection that when the Master was suffering from his sore throat and everybody was worried and anxious, young Subodh in all his innocence recommended tea to the Master as a sure remedy. The Master would also have taken it but medical advice was to the contrary.

Khoka Maharaj was easy of access, and everybody would feel very free with him. Many, on coming in contact with him, would feel his love so much that they would altogether forget the wide gulf of difference that marked their spiritual life and his. Yet he made no conscious attempt to hide the spiritual height to which he belonged. This great unostentatiousness was part and parcel of his very being. It was remarkably strange that he could mix so freely with one and all—with people of all ages and denominations—and make them his own. Many are the persons who, though not religiously minded, were drawn to him simply by his love and were afterwards spiritually benefited.

Compassionate heart

The young brahmacharins and monks of the Order found in him a great sympathizer. He took trouble to find out their difficulties and help them with advice and guidance. He would be their mouthpiece before the elders, mediate for them and shield them when they inadvertently did something wrong. One day a brahmacharin committed a great mistake, and was asked to live outside the monastery and to get his food by begging. The brahmacharin failed to get anything by begging except a quantity of fried gram and returned to the gate of the monastery in the evening. But he did not dare to enter the compound. Khoka Maharaj came to know of his plight, interceded on his behalf, and the young member was excused. The novices at the monastery had different kinds of work allotted to them. Often they did not know how to do it. Khoka Maharaj on such occasions would come forward to help and guide them.

He was self-reliant and would not accept personal services from others, even if they were devotees or disciples. He always emphasized that one should help oneself as far as possible, and himself rigidly adhered to this principle in his everyday life. Even during times of illness he was reluctant to accept any service from others, and avoided it until it became absolutely impossible for him to manage without.

His wants were few, and he was satisfied with anything that came unsought for. His personal belongings were almost nil. He would not accept anything except what was absolutely necessary for him. In food as in other things he made no choice and ate whatever came with equal relish. This great spirit of renunciation, always evidenced in his conduct, was the result of complete dependence on God. In personal conduct as well as in conversation he put much emphasis on self-surrender to God. He very often narrated to those who came to him for guidance the following story of Sridhar Swami, the great Vaishnava saint and a commentator on the Gita.

Spurred by a spirit of renunciation, Sridhar Swami was thinking of giving up the world when his wife died giving birth to a child. Sridhar felt worried about the baby and was seriously thinking how to provide for the child before retiring from the world. One day as he was sitting deeply absorbed with these thoughts, the egg of a lizard dropped from the roof in front of him. The egg broke as a result of the fall, and a young lizard came out. Just then a small fly came and stood near the young lizard, which caught and swallowed it in a moment. At this the thought flashed in the mind of Sridhar that there is a Divine plan behind creation, and that every creature is provided for beforehand by God. At once all his anxiety for his own child vanished, and he immediately renounced the world.

Mahasamadhi

Swami Subodhananda’s spiritual life was marked by as great a directness as his external life was remarkable for its simplicity. He had no philosophical problems of his own to solve. The Ultimate Reality was a fact to him. When he would talk of God, one felt that here was a man to whom God was a greater reality than earthly relatives. He once said, ‘God can be realised much more tangibly than a man feels the presence of the companion with whom he is walking.’ The form of his personal worship was singularly free from ritualistic observances. While entering the shrine, he was not obsessed by any awe or wonder, but would act as if he was going to a very near relation; and while performing worship he would not care to recite memorized texts. His relationship with God was just as free and natural as a human relationship. He realised the goodness of God, and so he was always optimistic in his views. For this reason his words would always bring cheer and strength to weary or despondent souls. Intellectual snobs or philosophical pedants were bewildered to see the conviction with which he talked on problems which they had not been able to solve, all their pride and self-conceit notwithstanding.

Towards the end, he suffered from various physical ailments, but his spiritual conviction was never shaken. While he was on his deathbed he said, ‘When I think of Him, I become forgetful of all physical sufferings.’ During this time, the Upanishads used to be read out to him. While listening, he would warm up and of his own accord talk of various deep spiritual truths. On one such occasion he said, ‘The world with all its enjoyment seems like a heap of ashes. The mind feels no attraction at all for all these things.’

While death was slowly approaching, he was unperturbed, absolutely free from any anxiety. Rather he was ready and anxious to meet the Beloved. The night before he passed away, he said, ‘My last prayer is that the blessings of the Lord be always on the Order.’ The great soul passed away on 2 December 1932.