Pali text, illustration and English translation of Dhammapada verse 345-346:

na taṃ daḷhaṃ bandhanamāhu dhīrā yadāyasaṃ dārujaṃ babbajaṃ ca |

sārattarattā maṇikuṇḍalesu puttesu dāresu ca yā apekhā || 345 ||

etaṃ daḷhaṃ bandhanamāhu dhīrā ohārinaṃ sithilaṃ duppamuñcaṃ |

etam’pi chetvāna paribbajanti anapekkhino kāmasukhaṃ pahāya || 346 ||

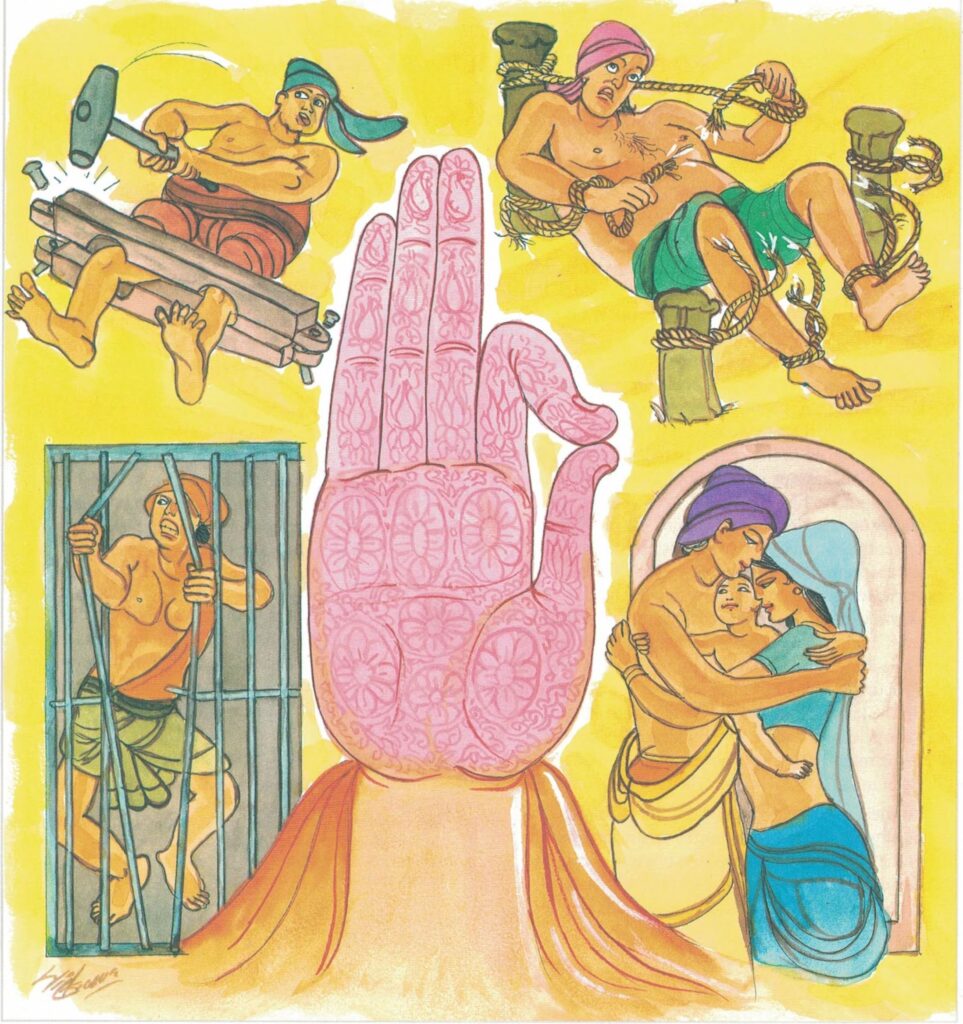

345. Neither of iron nor wood nor hemp is bond so strong, proclaim the wise, as passion’s yearning for sons, for wives, for gems and ornaments.

346. That bond is strong, proclaim the wise, down-dragging, pliable, hard to loose. This passion severed, they wander forth forsaking sensual pleasures.

The Prison-House

The story goes that once upon a time, criminals, house-breakers, highwaymen and murderers, were brought before the king of Kosala. The king ordered them to be bound with fetters, ropes, and chains. Now thirty country monks, desiring to see the Buddha, came and saw the Buddha, saluted him and took their leave. On the following day, as they went about Sāvatthi for alms, they came to the prison-house and saw those criminals. Returning from their alms-round, they approached the Buddha at eventide and said to him, “Venerable, today, as we were making our alms-rounds, we saw many criminals in the prisonhouse. They were bound with fetters, ropes, and chains, and were experiencing much suffering. They cannot break these fetters and escape. Is there any bond stronger than these bonds?”

In reply to their question, the Buddha said, “Monks, what do these bonds amount to? Consider the bond of the evil passions, the bond which is called craving, the bond of attachment for wealth, crops, sons, and wives. This is a bond a hundredfold, nay, a thousandfold stronger than these bonds which you have seen. But strong as it is, and hard to break, wise men of old broke it, and going to the Himālaya country, retired from the world.” So saying, he related the following:

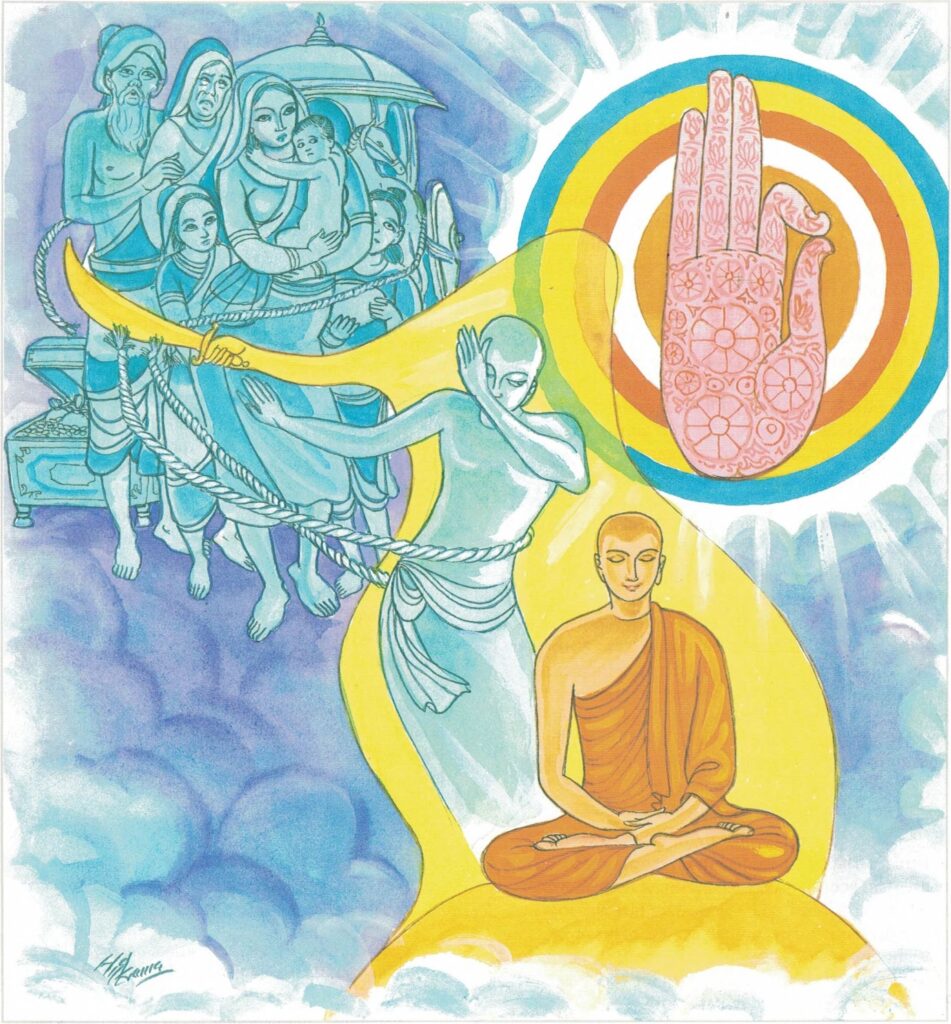

Story of the Past: Husband and wife

In times long past, when Brahmadatta was ruling at Benāres, the future Buddha was reborn in the family of a certain poor householder. When he reached manhood, his father died; so he worked for hire and supported his mother. His mother, in spite of his protests, brought him a certain daughter of respectable family to wife. After a time his mother died. In the course of time his wife conceived a child in her womb.

Not knowing that she had conceived a child, the husband said to the wife, “Dear wife, make your living by working for hire; I intend to become a monk.” Thereupon the wife said to the husband, “I have conceived a child in my womb. Wait until I give birth to the child and you see him, and then become a monk.” “Very well,” said the husband, promising to do so.

When the wife had given birth to her child, the husband took leave of her, saying, “Dear wife, you have given birth to your child in safety; now I shall become a monk.” But the wife replied, “Just wait until your son has been weaned from the breast.” While the husband waited, the wife conceived a second child.

The husband thought to himself, “If I do as she wishes me to, I shall never get away; I will run away and become a monk without so much as saying a word to her about it.” So without saying so much as a word to his wife about his plans, he rose up in the night and fled away. The city guards caught him. But he persuaded them to release him, saying to them, “Masters, I have a mother to support; release me.”

After tarrying in a certain place he went to the Himālaya country and adopted the life of an anchorite. Having developed the supernatural faculties and the higher attainments, he dwelt there, diverting himself with the diversion of the trances. And as he dwelt there, he thought to himself, “I have broken this bond which is so hard to break, the bond of the evil passions, the bond of attachment for son and wife.” So saying, he breathed forth a solemn utterance.

Explanatory Translation (Verse 345)

āyasaṃ dārujaṃ babbajañ yaṃ ca taṃ dhīrā daḷhaṃ bandhanaṃ

na āhu maṇikuṇḍalesu sārattarattā puttesu dāresu ca yā apekkhā

āyasaṃ [āyasa]: iron; dārujaṃ [dāruja]: of wood; babbajañ ca: of babus grass; taṃ: all these bonds; dhīrā: wise ones; daḷhaṃ bandhanaṃāhu: do not describe as ‘strenuous’; maṇikuṇḍalesu: to gem studded ear ornaments; sārattarattā: strongly attached; puttesu: to sons; dāresu: wives; yā apekkhā: if there is any desire

Explanatory Translation (Verse 346)

etaṃ dhīrā daḷhaṃ bandhanam āhu ohārinaṃ sithilaṃ duppamuñcaṃ

ohārinaṃ etaṃ pi chetvāna anapekkhino kāmasukhaṃ pahāya paribbajanti

etaṃ: this bond; dhirā: wise ones; daḷhaṃ bandhanam āhu: declare a strong bond; ohārinaṃ [ohārina]: pulls down; depraves; sithilaṃ [sithila]: slack; duppamuñcaṃ [duppamuñca]: not easy to get rid of, etaṃ pi: this bond too; chetvāna: having cut off; anapekkhino [anapekkhina]: with no yearning (for sensuality); kāmasukhaṃ [kāmasukha]: sensual pleasure; pahāya: having given up; paribbajanti: take to monastic life

The wise agree that this is a strong bond. It tends to deprave. Though this seems a lax knot, it is difficult to untie it to be free. However difficult the process is, freeing themselves from yearning for sensual pleasures, the wise leave household life and become ascetics.

Commentary and exegetical material (Verse 345-346)

ayasaṃ;dārujaṃ; babbajaṃ: these are all materials out of which fetters, bonds are made–iron-wood and grass (for ropes).

maṇikuṇḍalesu: gem-studded ear ornaments: jewellery.

sārattarattā: deeply attached.

ohārinaṃ: possessing the tendency to drag down, tending to depravity.

sithilaṃ: lax; slack. If a tie is lax, how can it prove a problem? Although it is lax, it restricts movement. One finds how restricting it is only when one tries to move towards the food.

duppamuñcaṃ: difficult to be untied.

anapekkhino kāmasukhaṃ: In order to initiate the move towards renunciation one has to cease yearning for sensual pleasures.

Kāmasukhaṃ: The pleasures of the senses.

At the outset the Buddha cautioned his disciples to avoid the two extremes. His actual words were: There are two extremes (antā) which should not be resorted to by a recluse (pabbajitena). Special emphasis was laid on the two terms antā which means end or extreme and pabbajita which means one who has renounced the world.

One extreme, in the Buddha’s own words, was the constant attachment to sensual pleasures (kāmasukhallikānuyoga). The Buddha described this extreme as base, vulgar, worldly, ignoble, and profitless.

This should not be misunderstood to mean that the Buddha expects all His followers to give up material pleasures and retire to a forest without enjoying this life. The Buddha was not so narrow-minded.

Whatever the deluded sensualist may feel about it, to the dispassionate thinker the enjoyment of sensual pleasure is distinctly short-lived, never completely satisfying, and results in unpleasant reactions. Speaking of worldly happiness, the Buddha says that the acquisition of wealth and the enjoyment of possessions are the source of pleasure for a layman. An understanding recluse would not however seek delight in the pursuit of these fleeting pleasures. To the surprise of the average man he might shun them. What constitutes pleasure to the former is a source of alarm to the latter to whom renunciation alone is pleasure.