Pali text, illustration and English translation of Dhammapada verse 334-337:

manujassa pamattacārino taṇhā vaḍḍhati māluvā viya |

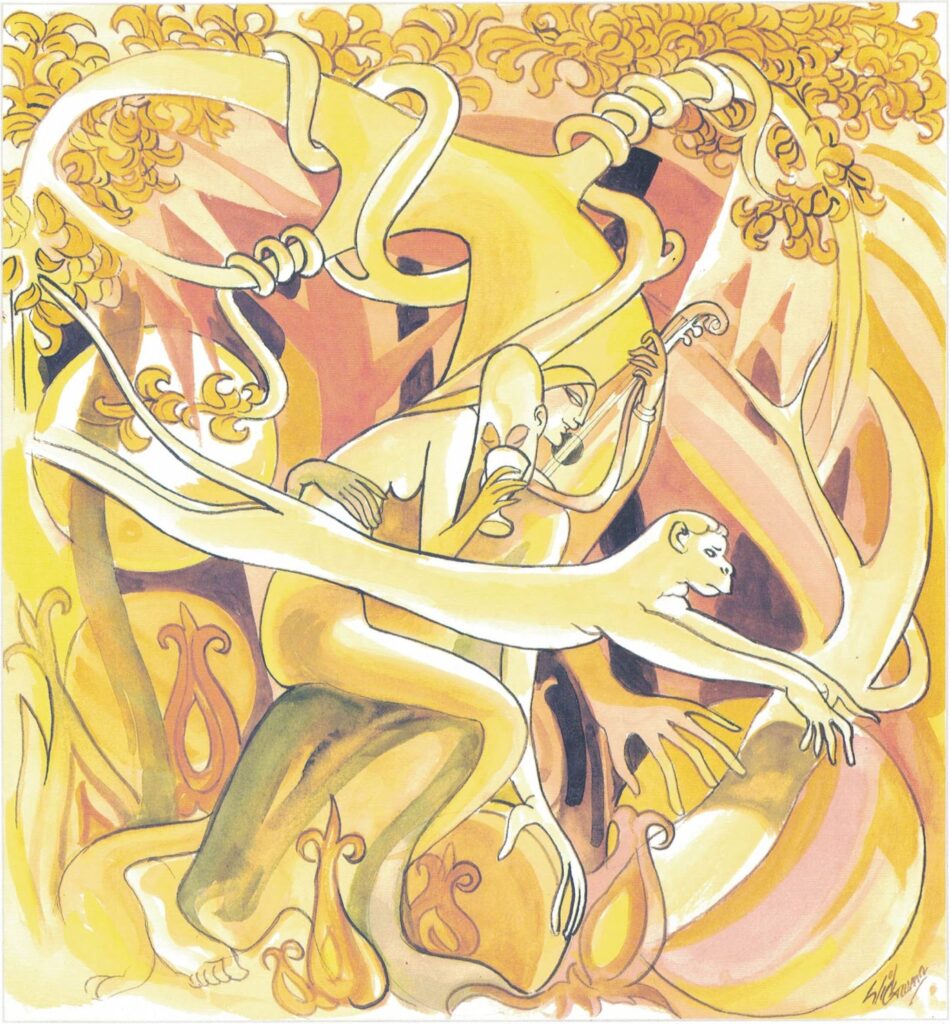

so palavati hurāhuraṃ phalam icchaṃ’va vanasmiṃ vānaro || 334 ||

yaṃ esā sahatī jammī taṇhā loke visattikā |

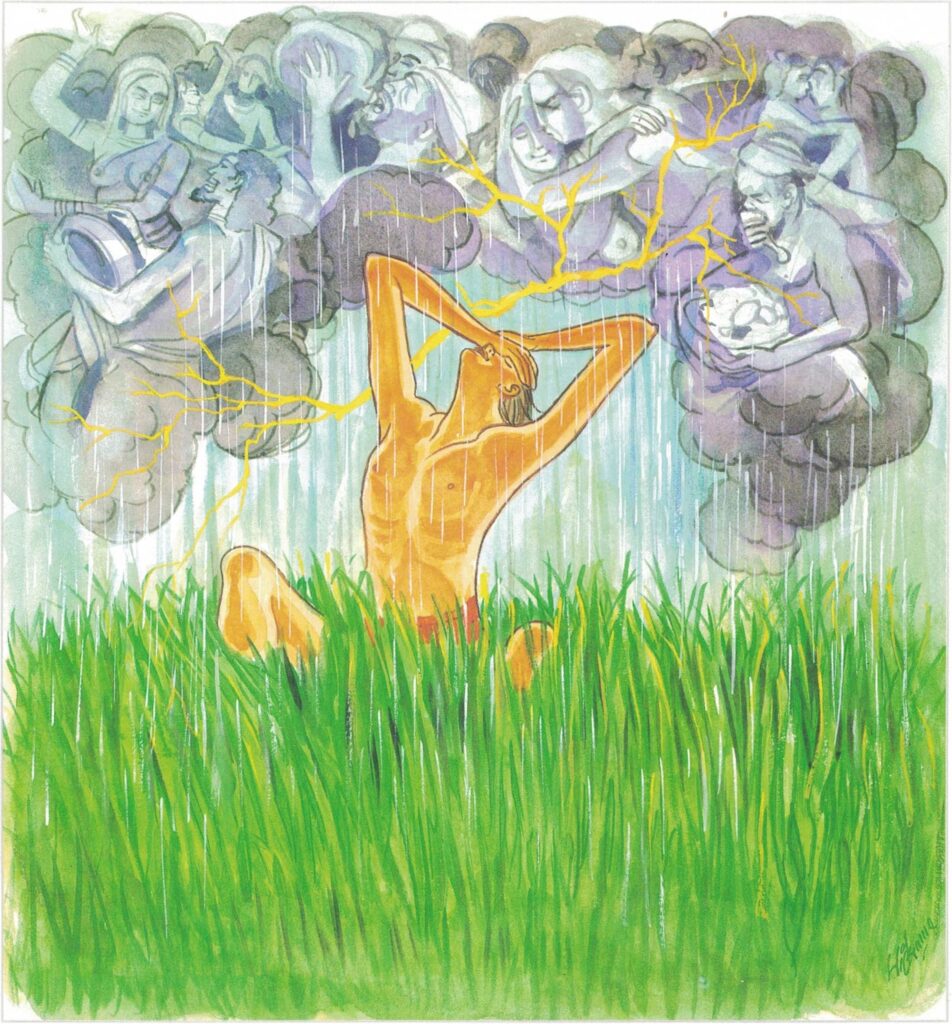

sokā tassa pavaḍḍhanti abhivaṭṭhaṃ’va bīraṇaṃ || 335 ||

yo c’etaṃ sahatī jammiṃ taṇhaṃ loke duraccayaṃ |

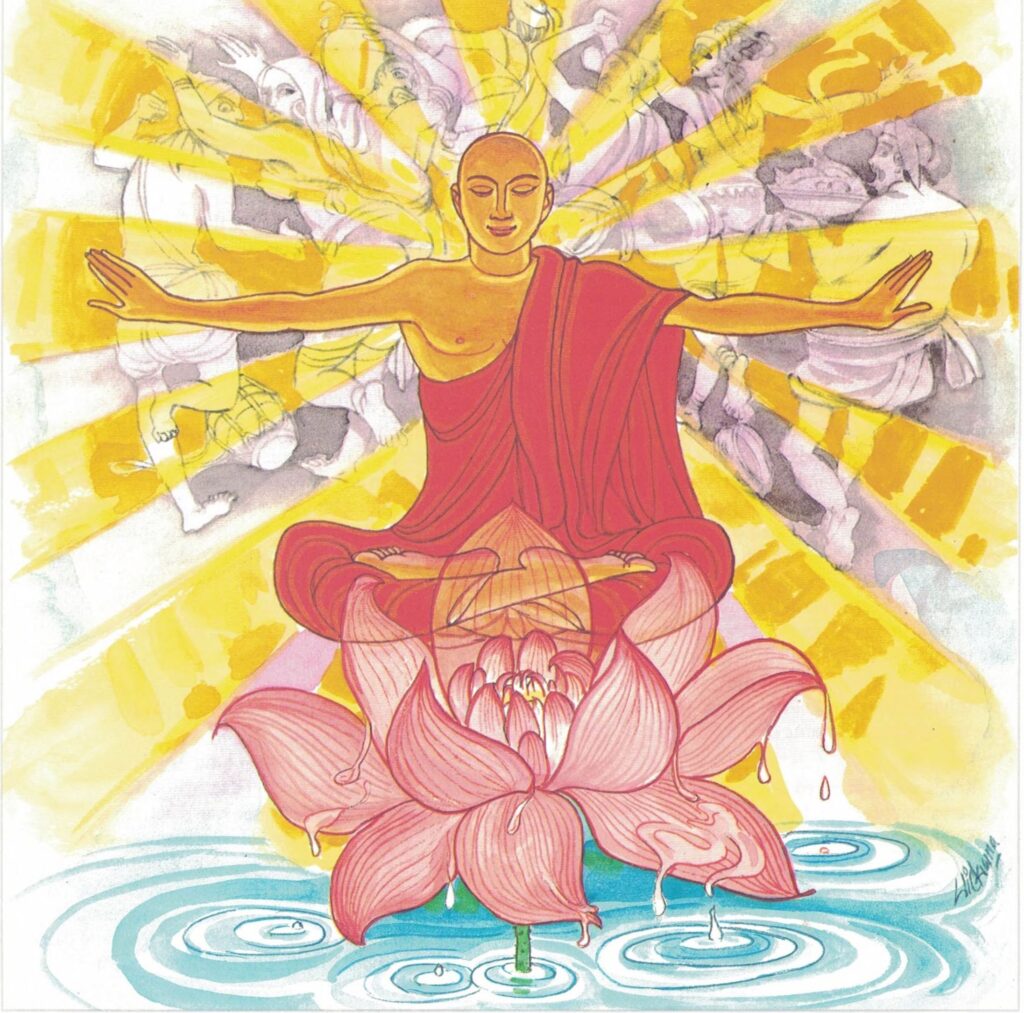

sokā tamhā papatanti udabindū’va pokkharā || 336 ||

taṃ vo vadāmi bhaddaṃ vo yāvant’ettha samāgatā |

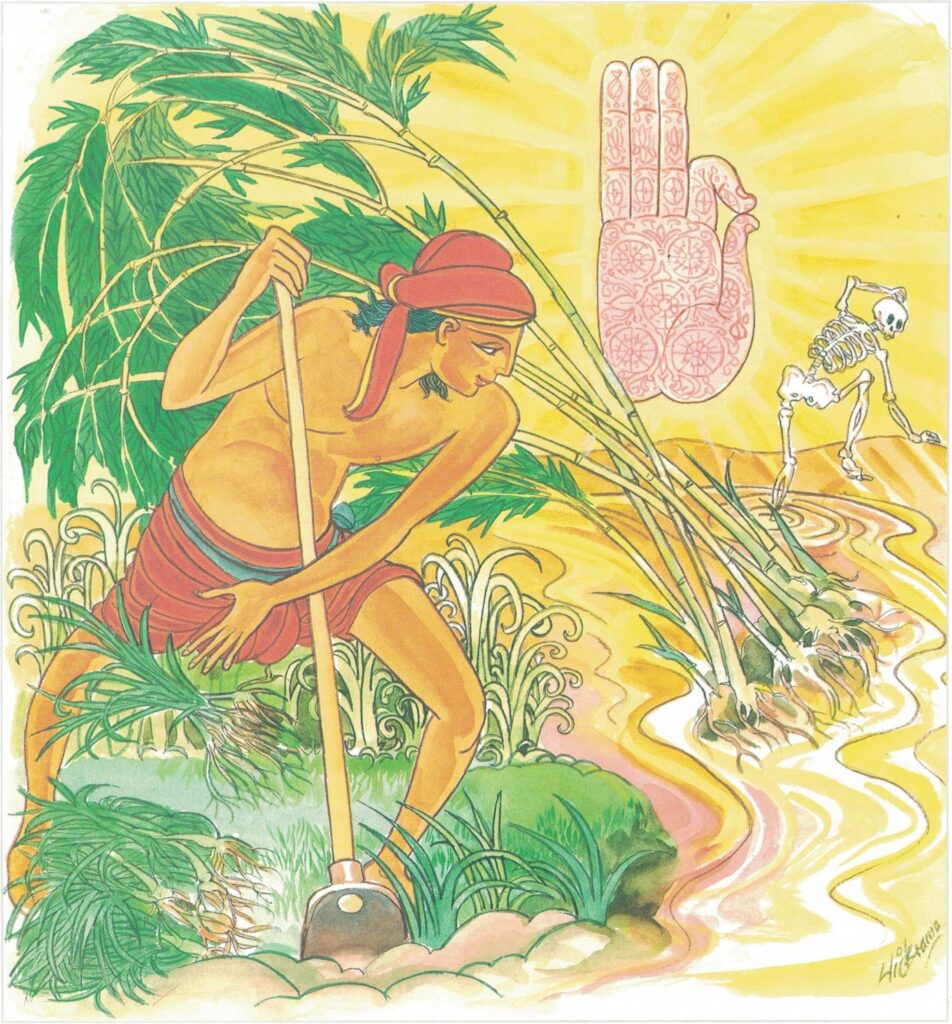

taṇhāya mūlaṃ khaṇatha usīrattho’va bīraṇaṃ |

mā vo nalaṃ’va soto’va māro bhañji punappunaṃ || 337 ||

334. As creeping ivy craving grows in one living carelessly. Like this, one leaps from life to life as ape in the forest seeking fruit.

335. Whomsoever in the world this wretched clinging craving routs for such a one do sorrows grow as grass well-soaked with rain.

336. But whoever in the world routs wretched craving hard to quell, from such a one do sorrows fall like water drops from lotus leaf.

337. Prosperity to you, I say, to all assembled here! When needing grass’s fragrant root so craving extirpate. Don’t let Māra break you again, again as a torrent a reed!

The Story of the Past: The Insolent Monk

The story goes that in times long past, when Buddha Kassapa passed into Nibbāna, two brothers of a respectable family retired from the world and became monks under their disciples. The name of the older brother was Sodhana, and that of the younger was Red Kapila. Likewise their mother Sādhinī and their younger sister Tāpanā retired from the world and became nuns. After the two brothers had become monks, they performed regularly and faithfully the major and minor duties to their teachers and their preceptors. One day they asked the following question, “Venerable, how many burdens are there in this religion?” and received the following answer, “There are two burdens: the burden of study and the burden of meditation.” Thereupon the older brother said, “I will fulfil the burden of meditation,” and for five years stayed with his teacher and his preceptor. Obtaining a meditation topic leading to arahatship, he entered the forest, and after striving and struggling with might and main, attained arahatship.

Said the younger brother, “I am young yet; when I am old, I will fulfil the burden of meditation.” Accordingly he assumed the burden of study and learned by heart the three Pitakas. By his knowledge of the texts, he gained a great following, and through his following, rich offerings. Drunk with the intoxication of great learning, and overcome with craving for gain, he was led by overweening pride of knowledge to pronounce a thing said by others, even when it was right, to be wrong; even when wrong, to be right; even when it was innocent, to be sinful; even when sinful, to be innocent. The kindly monks used to say to him, “Brother Kapila, do not speak thus:” and would admonish him, quoting to him the doctrine and the discipline. But Kapila would reply, “What do you know, empty-fists?” and would go about snubbing and disparaging others.

The monks reported the matter to his brother, Venerable Sodhana. Sodhana went to him and said, “Brother Kapila, for men such as you, right conduct is the life of religion; therefore you should not abandon right conduct, reject that which is right and proper and speak as you do.” Thus did Sodhana admonish his brother Kapila. But the latter paid no attention to what he said. However, Sodhana admonished him two or three times, but seeing that he paid no attention to his words, left him, saying, “Well, brother, you will become notorious for your doings.” And from that time on, the rest of the kindly monks would have nothing to do with him.

Thus did the monk Kapila adopt an evil mode of conduct and go about with companions confirmed like himself in an evil mode of conduct. One day he said to himself, “I will recite the Pātimokkha in the hall of discipline.” So taking a fan and seating himself in the seat of the Dhamma, he recited the Pātimokkha, asking the usual question, “Brethren, are there, among the monks who are here gathered together, any who have anything to confess?” The monks thought, “What is the use of giving this fellow an answer?” Observing that the monks all remained silent, he said, “Brethren, there is no doctrine or discipline; what difference does it make whether you hear the Pātimokkha or not?” So saying, he arose from the seat. Thus did he retard the teaching of the word of Buddha Kassapa.

Venerable Sodhana attained Nibbāna in that very state of existence. As for Kapila, at the end of his allotted term of life, he was reborn in the great hell of avīci. Kapila’s mother and sister followed his example, reviled and abused the kindly monks, and were reborn in that same Hell.

Now at that time there were five hundred men who made a living by plundering villages. One day the men of the countryside pursued them, whereupon they fled and entered the forest. Seeing no refuge there, and meeting a certain forest hermit, they saluted him and said to him, “Venerable, be our refuge.” The Venerable replied, “For you there is no refuge like the precepts of morality. Do you take upon yourselves, all of you, the five precepts.” “Very well,” agreed the bandits, and took upon themselves the five precepts. Then the Venerable admonished them, saying, “Now that you have taken upon yourselves the Precepts, not even for the sake of saving your lives, may you transgress the moral law, or entertain evil thoughts.” “Very well,” said the former bandits, giving their promise.

When the men of the countryside reached that place, they searched everywhere, and discovering the bandits, deprived all those bandits of life. So the bandits died and were reborn in the world of the gods; the leader of the bandits became the leading deity of the group. After passing through the round of existences forward and backward in the world of the gods for the period of an interval between two Buddhas, they were reborn in the dispensation of the present Buddha in a village of fishermen consisting of five hundred households near the gate of the city of Sāvatthi.

The leader of the band of deities received a new birth in the house of the leader of the fishermen, and the other deities in the houses of the other fishermen. Thus on one and the same day all received a new conception and came forth from the wombs of their mothers. The leader of the fishermen thought to himself, “Were not some other boys born in this village today?” Causing a search to be made, he learned that the companions had been reborn in the same place. “These will be the companions of my son,” thought he, and sent food to them all for their sustenance. They all became playfellows and friends, and in the course of time grew to manhood. The oldest of the fishermen’s sons won fame and glory and became the leading man of the group.

Kapila was tormented in hell during the period of an interval between two Buddhas, and through the fruit of his evil deeds which still remained, was reborn at this time in the Aciravatī River as a fish. His skin was of a golden hue, but he had stinking breath.

The Story of the Present: The Fishermen, and The Fish with a Stinking Breath

Now one day those companions said to themselves, “Let us snare some fish.” So taking a net, they threw it into the river. It so happened that this fish fell into their net. When the residents of the village of fishermen saw the fish, they made merry and said, “The first time our sons snared fish, they caught a goldfish; now the king will give us abundant wealth.” The companions tossed the fish into a boat and went to the king. When the king saw the fish, he asked, “What is that?” “A fish, your majesty,” replied the companions. When the king saw it was a goldfish, he thought to himself, “The Buddha will know the reason why this fish has a golden hue.” So ordering the fish to be carried for him, he went to the Buddha. As soon as the fish opened his mouth, the whole Jetavana stank. The king asked the Buddha, “Venerable, how did this fish come to have a golden hue? And why is it that he has stinking breath?”

“Great king, in the dispensation of Buddha Kassapa this fish was a monk named Kapila, and Kapila was very learned and had a large following. But he was overcome with desire of gain, and would abuse and revile those who would not take him at his word. Thus did he retard the religion of Buddha Kassapa, was therefore reborn in the avīci hell, and because the fruit of his evil deed has not yet been exhausted, has just been reborn as a fish. Now since for a long time he preached the word of the Buddha and recited the praises of the Buddha, for this cause he has received a golden hue. But because he reviled and abused the monks, for this cause he has come to have stinking breath. I will let him speak for himself, great king.” “Venerable, by all means let him speak for himself.”

So the Buddha asked the fish, “Are you Kapila?” “Yes, Venerable, I am Kapila.” “Where have you come from?” “From the Great Hell of Avīci, Venerable.” “What became of your older brother Sodhana?” “He passed into Nibbāna, Venerable.” “But what became of your mother Sādhinī?” “She was reborn in Hell, Venerable.” “And what became of your younger sister Tāpanā?” “She was reborn in hell, Venerable.” “Where shall you go now?” “Into the great hell of avīci, Venerable.” So saying, the fish, overcome with remorse, struck his head against the boat, died then and there, and was reborn in hell. The multitude that stood by were greatly excited, so much so that the hair of their bodies stood on end.

At that moment the Buddha, perceiving the disposition of mind of the company there assembled, preached the Dhamma in a way that suit the occasion:

A life of righteousness, a life of holiness,

This they call the gem of highest worth.

Beginning with these words, the Buddha recited in full the Kapila Sutta, found in the Sutta Nipāta.

Explanatory Translation (Verse 334)

manujassa pamattacārino taṇhā vaḍḍhati māluvā viya so

plavati hurādhuraṃ phalam icchaṃ vanasṃiṃ vānaro iva

manujassa: man’s; pamattacārino [pamattacārina]: of slothful ways; taṇhā: craving; vaḍḍhati: grows; māluvā viya: like the creeper that destroys trees; so: he; plavati: keeps on jumping; hurādhuraṃ [hurādhura]: from birth to birth; phalam icchaṃ [iccha]: fruit-loving; vanasṃiṃ [vanasṃi]: in the forest; vānaro iva: like a monkey

Man’s craving grows like the creeper māluvā. At the end, the creeper destroys the tree. Like the monkey that is not happy with the fruit in the tree, the man of craving keeps on jumping from one existence to another.

Explanatory Translation (Verse 335)

jammī visattikā esā taṇhā loke yaṃ sahatī

tassa abhivaṭṭhaṃ bīraṇaṃ iva sokā

jammī: lowly; visattikā: the poisonous and clinging; esā taṇhā: this craving; loke: in this world; yaṃ: if someone; sahatī: crushes; tassa: to that person; abhivaṭṭhaṃ [abhivaṭṭha]: exposed to repeated rains; bīraṇaṃ iva: like the bīraṇa grass; sokā: his sorrows; vaḍḍhanti: increase.

If someone is overcome by craving which is described as lowly and poisonous, his sorrows grow as swiftly and profusely as bīraṇa grass, after being exposed to repeated rains.

Explanatory Translation (Verse 336)

loke yo ca jammiṃ duraccayaṃ etaṃ taṇhā sahatī

tamhā sokā pokkharā udabindū iva papatanti

loke: here in this world; yo ca: if someone; jammiṃ [jammi]: lowly; duraccayaṃ [duraccaya]: that is difficult to be passed over; etaṃ taṇhā: this craving; sahatī: subdues; tamhā: from him; sokā: sorrows; pokkharā udabindū iva: like water off the lotus leaf; papatanti: slip away

Craving is a lowly urge. It is difficult to escape craving. But, in this world, if someone were to conquer craving, sorrows will slip off from him like water off a lotus leaf.

Explanatory Translation (Verse 337)

yāvanto ettha samāgatā vo bhaddaṃ taṃ vo vadāmi

usīrattho bīraṇaṃ iva taṇhāya mūlaṃ khanatha

nalaṃ soto iva māro vo punappunaṃ mā bhañji

yāvanto [yāvanta]: all those; ettha: here; samāgatā: have assembled; vo: all of you; bhaddaṃ [bhadda]: may be well; taṃ: therefore; vo: to you; vadāmi: I will give this advice; usīrattho [usīrattha]: those who seek the sweet-smelling usīra grass-roots; bīraṇaṃ iva: as they dig out bīraṇa grass; taṇhāya: of craving; mūlaṃ [mūla]: the root; khanatha: dig out; nalaṃ iva: uprooting the reeds; soto: the flood; māro: death; punappunaṃ [punappuna]: over and over; nabhañji: may not torture you

All those here assembled, may you all be well. I will advise you towards your well being. The person who is keen to get sweet-smelling usīra roots must first dig up the bīraṇa grass roots. In the same way, dig up the roots of craving. If you do that, Māra–death–will not torture you over and over like a flood crushing reeds.

Commentary and exegetical material (Verse 334-337)

māluvā viya: like the māluvā creeper. Māluvā creeper is a parasite growing upon trees. The creeper embraces the tree and eventually destroys it. Similarly, the craving that grows in the mind of a person destroys it.

phalaṃ icchaṃ vānaro viya: like the monkey seeking fruit. The monkey is not happy with the fruit in that tree only. He keeps on jumping from tree to tree.

visattikā: the term visattikā is given to craving for several reasons. It is called so because it entangles. Because it is poisonous too, craving is given this name.

bīraṇa grass: This is a variety of grass that grows swiftly. After being exposed to repeated rains, it grows even faster. Sorrow is described as bīraṇa grass after several rains.

duraccayaṃ: craving is a potent temptation, It is difficult to be ignored–to be overlooked.

usīra grass: The root of the usīra grass smells sweet. In order to get at it, first the bīraṇa grass has to be cleared away. Therefore, in order to get to higher states, you must first uproot craving.

The verses in this instance arise out of an encounter with some people who caught a strange fish. This incident indicates the remarkable range of people the Buddha met. The following is another instance of the Buddha meeting with an ordinary farmer:

The hungry farmer of Ālavi: One morning, the Buddha left the Jetavana Monastery in the company of five hundred monks, and arrived at Ālavi for the sake of a poor farmer. The people of Ālavi invited the Buddha and the fraternity of monks to alms. After the meal, when the time came for the preaching and making over the merits, the Buddha remained silent.

The poor farmer who heard of the arrival of the Buddha in Ālavi had to look for a lost bull and spend the whole morning in the search of it. He came back, oppressed with hunger. However, without going home for food, he came to the place where the Buddha was seated, with the idea of worshipping the Buddha.

When the farmer came and saluted the Buddha, and remained aside, the Buddha asked the attendants whether any food was left. When they answered in the affirmative, the Buddha asked them to feed him. After he finished the meal, the Buddha delivered a discourse, and at the end of it the farmer realized the fruit of sotāpatti.

On the way back, the monks began to talk about this sympathetic act of the Buddha. While standing on the road, the Buddha explained that no preaching could be understood by a person when afflicted with hunger. Several in the crowd realized fruits such as sotāpatti.

Another instance of the Buddha’s meetings with people in various human situations is presented by the following story:

The boys who were attacking a serpent: One day, while the Buddha was staying at the Jetavana Monastery in Sāvatthi, He went on his round for alms in the afternoon in the city. At a spot not far from the monastery, the Buddha saw a large number of boys attacking a serpent with sticks.

“What are you doing, boys” asked the Buddha.

“We are attacking this serpent with a stick”, the boys replied.

“Why do you want to kill the serpent?” asked the Buddha.

“Out of fear that the serpent would bite us.”

The Buddha admonished them thus: Those who, in search of happiness, attack others who desire happiness, gain nothing good in the end. Similarly, those who, in search of happiness, refrain from attacking others who desire happiness arrive at bliss afterwards.

At the end of the admonition, the boys realized the fruit of sotāpatti.