Pali text, illustration and English translation of Dhammapada verse 174:

andhabhūto ayaṃ loko tanuk’ettha vipassati |

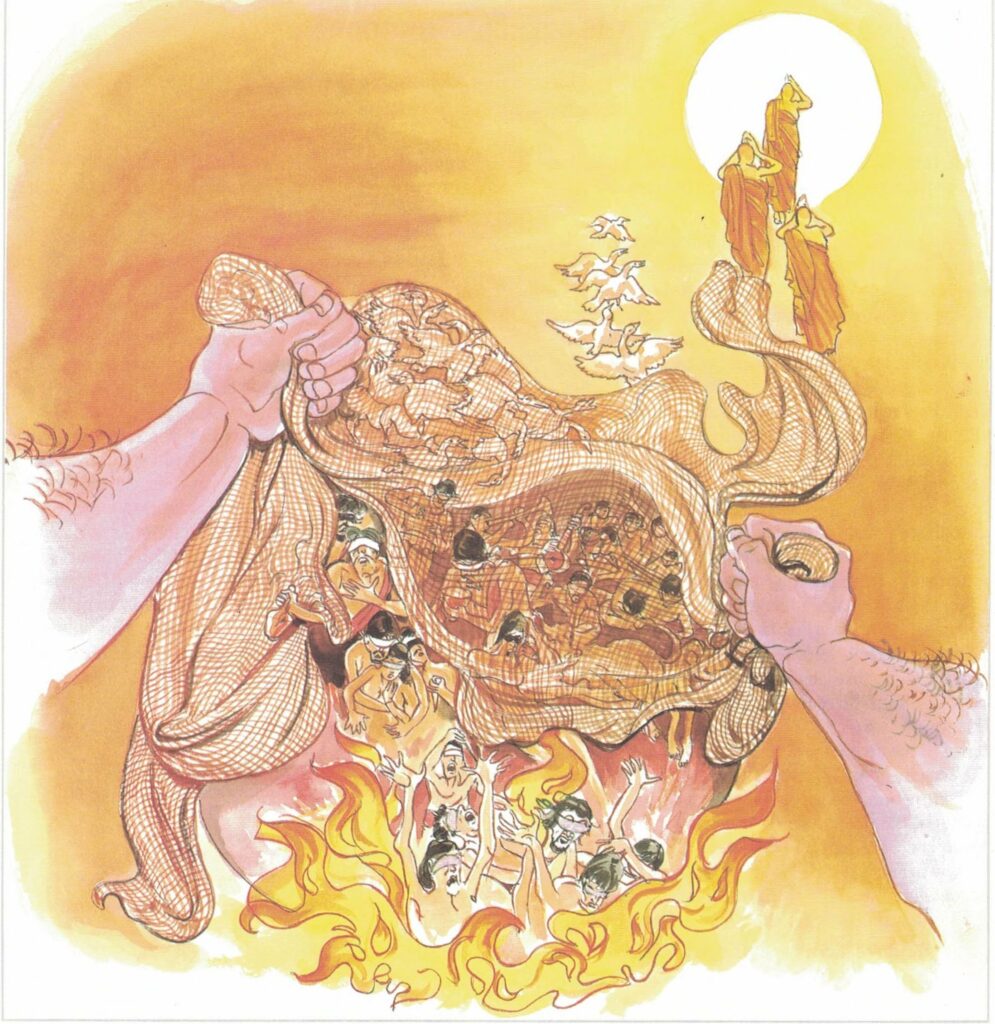

sakunto jālamutto’va appo saggāya gacchati || 174 ||

174. This world is blind-become few are here who see within as few the birds break free from net so those who go to heavens.

Among thousands of men, one strives for perfection and even among those who strive and succeed, one knows Me in essence.

— Bhagavad Gita 7.3

The Story of the Weaver-Girl

While residing at the Monastery near Aggāḷava shrine in the country of Āḷavi, the Buddha spoke this verse, with reference to a young maid, who was a weaver.

At the conclusion of an alms-giving ceremony in Āḷavi, the Buddha gave a discourse on the impermanence of the aggregates (khandhās). The main points the Buddha stressed on that day may be expressed as follows: “My life is impermanent: for me death only is permanent. I must certainly die: my life ends in death. Life is not permanent: death is permanent.” The Buddha also exhorted the audience to be always mindful and to strive to perceive the true nature of the aggregate. He also said, “As one who is armed with a stick or a spear is prepared to meet an enemy (e.g., a poisonous snake), so also, one who is ever mindful of death will face death mindfully. He would then leave this world for a good destination (sugati). Many people did not take the above exhortation seriously, but a young girl of sixteen who was a weaver clearly understood the message. After giving the discourse, the Buddha returned to the Jetavana Monastery.

After a lapse of three years, when the Buddha surveyed the world, he saw the young weaver in his vision, and knew that time was ripe for the girl to attain sotāpatti fruition. So the Buddha came to Āḷavi to expound the Dhamma to the second time. When the girl heard that the Buddha had come again with five hundred monks, she wanted to go and listen to the discourse which would be given by the Buddha. However, her father had also asked her to wind some thread spools which he needed urgently, so she promptly wound some spools and took them to her father. On the way to her father, she stopped for a moment at the edge of the audience, assembled to listen to the Buddha.

Meanwhile, the Buddha knew that the young weaver would come to listen to his discourse: he also knew that the girl would die when she got to the weaving shed. Therefore, it was very important that she should listen to the Dhamma on her way to the weaving shed and not on her return. So, when the young weaver appeared on the fringe of the audience, the Buddha looked at her. When she saw him looking at her, she dropped her basket and respectfully approached the Buddha. Then, he put four questions to her and she answered all of them. Hearing her answers, the people thought that the young weaver was being very disrespectful. Then, the Buddha asked her to explain what she meant by her answers, and she explained. “Venerable! Since you know that I have come from my house, I interpreted that, by your first question, you meant to ask me from what past existence I have come here. Hence my answer, ‘I do not know;’ the second question means, to what future existence I would be going from here; hence my answer, ‘I do not know;’ the third question means whether I do know that I would die one day; hence my answer, ‘Yes, I do know;’ the last question means whether I know when I would die; hence my answer, ‘I do not know.’” The Buddha was satisfied with her explanation and he said to the audience, “Most of you might not understand clearly the meaning of the answers given by the young weaver. Those who are ignorant are in darkness, they are unable to see.” Then, she continued on her way to the weaving shed. When she got there, her father was asleep on the weaver’s seat. As he woke up suddenly, he accidentally pulled the shuttle, and the point of the shuttle struck the girl at her breast. She died on the spot, and her father was broken-hearted. With eyes full of tears he went to the Buddha and asked the Buddha to admit him to the Sangha. So, he became a monk, and not long afterwards, attained arahatship.

Explanatory Translation (Verse 174)

ayaṃ loko andhabhūto ettha tanuko vipassati

jālamutto sakunto iva appo saggāya gacchati

ayaṃ loko: these worldly persons; andhabhūto [andhabhūta]: are blind; ettha: of them; tanuko [tanuka]: a few; vipassati: are capable of seeing well; jālamutto [jālamutta]: escaped from the net; sakunto iva: like a bird; appo: a few; saggāya gacchati: go to heaven

Most people in this world are unable to see. They cannot see reality properly. Of those, only a handful are capable of insight. Only they see well. A few, like a stray bird escaping the net, can reach heaven.

Commentary and exegetical material (Verse 174)

andhabhūto: blind. The worldly people, who cannot perceive the way to liberation are described here as the blind. The handful capable of “seeing” escape the net of worldliness and reach heaven.

Sagga: blissful states, not eternal heavens.