Early Life

Each disciple of Sri Ramakrishna was great in his own way. Each had superb qualities which dazzled those who witnessed them. Swami Turiyananda was a blazing fire of renunciation. To be near him was to feel the warmth of his highly developed spiritual personality. From his very boyhood till the end, his life was a great fight: in the beginning, it was a fight for his own spiritual evolution; during the later days, to make those who came within the orbit of his influence better. He was as if ceaselessly alert and vigilant so that everything in and around him might be the expression of the highest spirituality. Yet it meant no struggle to him; it became so very natural with him. His early life was modelled on the teachings of Shankaracharya, and those who witnessed him in later days could witness in him a living example of a Jivanmukta (free while still in the body). Swami Vivekananda once, in his characteristic way of presenting a point of view in the most emphatic and impressive manner, even belittling himself and his own achievements, said to his American disciples, ‘In me you have seen the expression of kshatriya power; I am going to send to you one who is the embodiment of brahminical qualities, who represents what a brahmin or the highest spiritual evolution of man is.’ And he sent Swami Turiyananda.

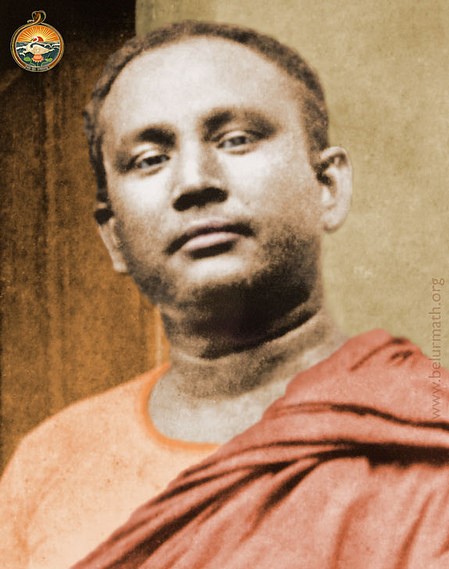

Swami Turiyananda was born in a brahmin family in North Calcutta on 3 January 1863. His family name was Harinath Chattopadhya. He lost his parents while very young, and was brought up by his elder brother. He could not prosecute his studies beyond the Entrance class as his interest lay in another direction. From a very young age, he would live like an orthodox brahmacharin—bathing three times a day, cooking his own meal, and reciting the whole of the Gita before daybreak. He was a deep student of the Upanishads, and the works of Shankaracharya. His mind was bent towards the Advaita Vedanta, and he strove sincerely to live up to that ideal. The story goes that once when he was bathing in the Ganga, something looking like a crocodile popped up in the river, and a shout was raised around asking the bathers to run up. His first reaction was to leave the water and come to the bank for the safety of his life. At once the thought occurred to him:

‘If I am one with Brahman, why should I fear? I am not a body. And if I am Spirit, what fear have I from anything in the whole world, much less from a crocodile?’

This idea so much stirred his mind that he did not leave the spot. Bystanders thought he was foolishly courting death. But they did not know that he was testing his faith in Advaita philosophy. The purpose of his life was to be a Jivanmukta. He himself once said that the first time he read the verse in which it is said that life is meant for the realisation of Jivanmukti, he leapt in joy. For that was the ideal he was aiming at.

The scriptures say that if a man is sincere he meets with his spiritual guide unsought for. Harinath also met with his Master unexpectedly and without knowing it. He was then a boy of thirteen or fourteen. He heard that a Paramahamsa (a sannyasin of the highest order—a realised soul) would come to a neighbouring house. Out of curiosity, he went to see the Paramahamsa. This Paramahamsa was no other than Sri Ramakrishna, who afterwards played a great part in moulding his life. To give the version of Swami Turiyananda himself: ‘A hackney carriage with two passengers in it stopped in front of the house. A thin emaciated man got down from the carriage supported by another man. He appeared to be totally unconscious of the world. When I got a better view of him, I saw that his face was surrounded with a halo. The thought immediately flashed in my mind, “I have read about Shukadeva in scriptures. Is this then a man like him?” Supported by his attendant, he walked to the room with a tottering gait. Regaining a little consciousness of the world, he saw a large portrait of Kali on the wall and bowed his head before it. Then he sang a song depicting the oneness of Krishna and Kali which thrilled the audience.’

With Sri Ramakrishna

He met Sri Ramakrishna again at Dakshineswar two or three years afterwards. Soon he became passionately devoted to the Master and began to see him as often as he could. The Master asked Harinath to come to him avoiding holidays when there was a large assemblage of visitors. Thus Harinath found an opportunity to talk very freely and intimately with the Master, who was rather surprised to know from young Hari that his favourite book was the Rama Gita, an Advaita treatise. In the course of conversation one day, Harinath told the Master that he found great inspiration while he visited Dakshineswar, whereas in Calcutta he felt miserable. To this appealing statement of the young disciple, the Master said, ‘Why, you are a servant of the Lord Hari, and His servant can never be unhappy anywhere.’ ‘But I don’t know that I am His servant’, remonstrated the boy. The Master reiterated, ‘Truth does not depend upon anybody’s knowledge of it. Whether you know it or not, you are a servant of the Lord.’ This reassured Harinath.

From an early age, Harinath had an abhorrence of women. He did not allow even little girls to come near him. One day in answer to an inquiry from the Master on this subject he said, ‘Oh, I cannot bear them.’ ‘You talk like a fool!’ said the Master reprovingly, ‘Look down upon women! What for? They are the manifestation of the Divine Mother. Bow down to them as to your mother and hold them in respect. That is the only way to escape their influence. The more you hate them, the more you will fall into their snare.’ These fiery words penetrated into the heart of Harinath and changed his entire outlook on women.

One day Harinath asked the Master how one could completely get rid of the sex-idea. The reply was that one had no need to think in that line. One should try to think of positive ideas, of God, then only one would be free from any sex-idea. This was a new revelation to the young boy.

We have said that Harinath was a deep student of Vedanta and tried to mould his life according to its teachings. Once he happened to keep away from Dakshineswar for a longer time than usual. When he came next, the Master told Harinath, ‘They say you are studying and meditating on Vedanta nowadays. It is good. But what does the Vedanta philosophy teach? “Brahman alone is real and everything else is unreal” isn’t that its substance, or is there anything more? Then why don’t you give up the unreal and cling to the Real?’ These words pinpointed the main theme of Vedanta in such a clear way that they turned the thoughts of Harinath in a new fruitful direction.

A few days later, the Master went to Calcutta and sent for Harinath; when he came, he found the Master in a state of semi-consciousness. ‘It is not easy to see the world of phenomena as unreal’, the Master began addressing the assembled devotees, ‘This knowledge is impossible without the special grace of God. Mere personal effort is powerless to confer this realisation. A man is after all a tiny creature with very limited powers. What an infinitesimal part of truth can he grasp by himself!’ Harinath felt as if these words were directed to him, for he had been straining every nerve to attain illumination by personal effort. The Master then sang a song eulogizing the miraculous power of divine grace and decrying egotism. Tears flowed down his cheeks, literally wetting the ground. Harinath was deeply moved.

He too burst into tears. After that, he learnt to surrender himself at the feet of the Lord.

Sri Ramakrishna loved Harinath dearly. In order to induce Harinath to be more regular in his visits to Dakshineswar, the Master appealed to him thus in a voice choked with emotion, ‘Why don’t you come here? I love to see you all because I know that your are God’s special favourites. Otherwise what can I expect from you? You have not the means to offer me a pice worth of presents, nor have you a tattered mat to spread on the floor when I go to your house. And still I love you so much. Don’t fail to come here (meaning himself), for this is where you will receive everything. If you are sure to find God elsewhere, go there by all means. What I want is that you realise God, transcend the misery of the world, and enjoy divine beatitude. Anyhow try to attain it in this life. But the Mother tells me that you will realise God without any effort if you only come here. So I insist upon your coming.’ As he spoke thus he actually wept.

It is needless to say Harinath also had extraordinary veneration for the Master. In later days when he was severely suffering from various physical ailments, he once remarked that the bliss he had got in the company of the Master more than compensated for all the suffering he had had in his whole life. After the passing away of the Master when the monastery at Baranagore had been established, Harinath joined it in 1887 at the age of twenty-four years. After formally accepting the vow of lifelong monasticism, his new name became Swami Turiyananda, though he was popularly known as Hari Maharaj.

As a wandering Monk

The sannyasin’s love for freedom made some of these young monks feel that they must go out in the wide world depending solely on God and gathering spiritual experiences from the hardships and difficulties of life. Hari Maharaj also left the shelter of the Baranagore Math and for years travelled on foot from one holy city to another, practising the most rigorous austerities. He had often scarcely the barest necessities about him—at times not even a blanket. The severe winter of Northern India he passed with a cotton chaddar, and for his food, he had what chance might bring. He travelled through the Uttar Pradesh and stayed for some time at Rajpur, near Dehradun, and it was here that an astrologer told him he would soon meet one whom he most liked. In a day or two he, to his great surprise, met Swami Vivekananda, who was accompanied by some other gurubhais. Hari Maharaj joined the party and practised Tapasya at Rishikesh, the famous retreat of monks, a few miles above Hardwar. After Swamiji had recovered from the severe fever which he had here, he went to Meerut to recoup his health, and from there to Delhi. Hari Maharaj was also one of the party which accompanied him. Hari Maharaj again travelled with him from Bombay to Abu Road, when the latter was about to depart for America in 1893. He used to say later that from the radiant form of Swamiji he could at once judge that he had perfected himself in sadhana and was ready to impart to mankind the results of his experience. At Abu Road, Swamiji told Swami Turiyananda, ‘Haribhai (brother Hari, by which affectionate name he called him), I don’t know what I have gained by austerities and spiritual practices, but this I find, that from the experience of travel throughout India my heart has expanded. I feel intensely for the poor, the afflicted, the distressed people of India. Let me see if I can do anything for them.’

Talking of his days of itineracy, he once said, Though I travelled much, I also studied much all along. At Vrindavan I studied a great deal of bhakti scriptures. It is not good to wander much if you do not at the same time continue your sadhana.

‘In the Jagannath temple at Puri, suddenly a sound came to my ears and my heart was filled with great joy so much so that I felt like walking in the air. The sound continued in various strains. My whole mind felt attracted. I then remembered what I had heard of Anahata Dhvani (music of the spheres, as it is called), and I thought it must be that.

‘One night at Ujjain I was sleeping under a tree. A storm came and suddenly someone touched me. I got up, and just then a branch fell where I had slept.’

Sometime during this period, he visited the celebrated Himalayan shrines of Kedarnath and Badrinarayan, and he stayed for a period at Srinagar (Garhwal).

Talking of the days in Garhwal, Hari Maharaj once said, ‘I was continuously in an exalted mood. My only idea was to realise Him. I not only committed to memory eight Upanishads, but used to be absorbed in the meaning of each mantra.’ He also prayed to the Divine Mother at this time with eyes soaked in tears that all book-learning might be wiped off from his mind. For the thing which he wanted was God-realisation and not dry intellectualism. He was a master of his senses, and once he sat down to meditate, external troubles could not reach the inner sanctuary of his mind. He spoke of this later to a monk of the Ramakrishna Order, ‘When I sit down for meditation, I lock the entrances to my mind, and after that nothing external can reach there. When I unlock them, then only can the mind cognise things outside.’ On another occasion, he remarked to a young sannyasin, ‘Write in big characters on the doors of your mind “No Admission” and no outside disturbance will trouble you during meditation. It is because you allow outside things to disturb you that they have access to your mind.’ During this wandering life one day he had a very interesting experience. While he was travelling from place to place on foot, the thought began to torment him that whereas everyone was doing something in this world, he was living only a useless vagrant life. He could not shake off this thought however much he tried. At last it became so oppressive to him that he threw himself down under a tree. There he fell asleep and had a dream. He saw himself lying on the ground, and then he saw that his body began to expand in all directions. It went on expanding till it seemed to cover the whole world. Then it occurred to him: ‘See how great you are, you are covering the whole world. Why do you think your life is useless? A grain of Truth will cover a whole world of delusion. Get up, be strong, and realise the Truth. That is the greatest life.’ He awoke and jumped up, and all his doubts vanished. In his travels of some parts of Uttar Pradesh and Punjab, he was accompanied by Swami Brahmananda. At this time Swamiji was writing from America to his brother disciples to meet together and organise themselves into a band for the spread of the message of the Master. At first Swami Turiyananda did not pay any heed to such an idea. His love for a life of tapasya was too great for him to think of anything else. But at long last he responded to the call and returned to the Math which was then at Alambazar. Swami Vivekananda had a great admiration for this brother disciple. In a letter from America he wrote in 1895, ‘Whenever I think of the wonderful renunciation of Hari, about his steadiness, of intellect and forbearance, I get a new access of strength!’ Swami Turiyananda’s love for Swamiji also was unique. He would be ready to sacrifice anything for one whom the Master dubbed as the leader of the party.

At the Alambazar Math, Hari Maharaj, at the suggestion of Swamiji, took upon himself the task of training the novitiates of the Order. He began to help them in meditation and in studying the scriptures like the Gita, the Upanishads. He began to take public classes as well in North Calcutta.

American work

In 1899, when Swami Vivekananda started for America for the second time, he persuaded Swami Turiyananda to accompany him for the American work. Hari Maharaj being a man of meditation was averse to the life of public preaching. So Swamiji found it hard, in the beginning, to persuade him to go to America. When all arguments failed, Swami Vivekananda put his arms around his neck and actually wept like a child as he uttered these words:

Dear Haribhai, can’t you see I have been laying down my life, inch by inch, in fulfilling this mission of the Master, till I am on the verge of death! Can you merely look on and not come to my help by relieving me of a part of my great burden?

Swami Turiyananda was overpowered and all his hesitation gave way to the love he bore for the leader.

They reached New York via England towards the end of August 1899. Hari Maharaj worked at first at the Vedanta Society of New York, and then he took up additional work at Mont Clair—a country town, about an hour’s journey from New York. Both at New York and Mont Clair the Swami made himself beloved of all. He carried the Indian atmosphere about him wherever he went. When he came to America, he said to Swamiji that platform work was not in his temperament. At this Swamiji told him that if he lived the life, that would be enough. Yes, Swami Turiyananda lived the life. Intensely meditative, gentle, quiet, unconcerned about the things of the world, Swami Turiyananda was a fire of spirituality. His very presence was a superb inspiration. He did not care much for public work and organisation. He was for the few, not for big crowds. His work was with the individual character building. And the greatest scope for work in this line he got when he lived with a group of students in the Shanti Ashrama at California.

A Vedanta student of New York, feeling the great need of a Vedanta retreat in the West where the students could live like Indian sannyasins, offered to Swami Vivekananda a homestead in California—160 acres of free government land situated in San Antone Valley—about forty miles from the nearest railway station and market. The place was naturally very solitary, and in addition it commanded a very beautiful scenery. Far, far away from human habitation, the place stretched out in a rolling, hilly country. Oak, Pine, Chaparral, Chamisal, and Manzanita covered part of the land, the other part was flat and covered with grass. Swamiji accepted the gift and sent Hari Maharaj to open an Ashrama there.

From New York Swami Turiyananda went first to Los Angeles and stayed there for a short while. Teaching and talking and holding classes, the Swami became popular in Los Angeles. But he could not stay there in spite of the earnest entreaties of the students, for he had come for other work. From Los Angeles he went to San Francisco, and stayed there for some time before he actually started for the Shanti Ashrama. It was at San Francisco that Swamiji had told the students, ‘I have only talked, but I shall send you one of my brethren who will show you how to live what I have taught.’ The students eagerly longed for the coming of the Swami about whom Swami Vivekananda spoke so highly, and naturally they expected much of him. Their expectation was more than fulfilled, for in Swami Turiyananda they found a living embodiment of Vedanta. During his short stay at San Francisco, Hari Maharaj gave a great impetus to the students who had formed themselves into the Vedanta Society of San Francisco.

With the first batch of a dozen students he one day left San Francisco for his future work in the San Antone Valley. When the party arrived there, many initial difficulties presented themselves. Except for one old log cabin, there was no shelter. Water had to be brought from a long distance. But the enthusiasm of the students at the prospect of a future Ashrama was unbounded. Gradually things took shape. Tents were pitched, a well was dug, and a meditation cabin was erected. Though the students were accustomed to the comforts of city life—some of them bred up in wealth and luxury—they all braved any difficulty that came in the way. Soon they were in a position to devote their individual attention to spiritual practices.

At this place Swami Turiyananda lived in one of his most intense spiritual moods—day and night talking only of God and the Divine Mother and allowing no secular thought to disturb the atmosphere of the Ashrama. The minds of the students were constantly kept at a high pitch through classes in meditation, the study of scriptures, and so on. With the Swami there was no special time of instruction. He was always in such an exalted mood that to any topic he would spontaneously, and unconsciously as it were, give a spiritual turn. There was no set of definite rules for the Ashrama, but the very life of the Swami was so very inspiring that everything in the Ashrama went on in an orderly and systematic way. Once a student actually asked Hari Maharaj to formulate a set of rules and regulations. ‘Why do you want rules?’ the Swami said, ‘Is not everything going on nicely and orderly without formal rules? Don’t you see how punctual everyone is, how regular we all are? The Divine Mother has made Her own rules, let us be satisfied with that. We have no organisation, but see how organised we are. This is the highest organisation: it is based on spiritual laws.’

In later days it was found that his method of chastisement was unique. He had a very loving heart, but usually he would keep his emotions under control and not give free play to them. Therefore a little reserved or a slightly apathetic attitude on his part helped to set the delinquent right. Once, to a young monk who was laughing loudly to the disturbance of others in an Ashrama in India, the Swami said by way of reproof, ‘Well, have you realised God, have you attained life’s goal, that you can give yourself up so wholeheartedly to laughter?’ A man of God as he was, he could not but talk in that strain even while scolding. Once interrogated by a curious student as to how men and women of pronounced and different temperaments were living so peacefully together in the Shanti Ashrama, the Swami said, ‘As long as we remain true to the Mother there is no fear that anything will go wrong. But the moment we forget Her, there will be great danger. Therefore I always ask you to think of the Mother.’ In those days the word ‘Mother’ was constantly on his lips. Referring to this period, he once remarked, ‘I could palpably see how Mother was directing every single footfall of mine.’

At times fiery exhortation came from the Swami to the students to make God-realisation the only aim of life. ‘Clench your fists and say: I will conquer! Now or never—make that your motto, even in this life I must see God’, the Swami would exhort. ‘That is the only way. Never postpone. What you know to be right, do that and do that at once, do not let any chance go by. The way to failure is paved with good intentions. That will not do. Remember, this life is for the strong, the persevering: the weak go to the wall. And always be on your guard. Never give in.’

Sri Ramakrishna used to say, ‘If a cobra bites a man, its poison will have sure effect; in the same way, if a man comes in contact with a really spiritual person, his life is sure to be changed.’ Those who came in touch with Swami Turiyananda or received training under him, were transformed—metamorphosed. In America as well as in India many are the persons whose outlook on life entirely changed because of his influence. Afterwards he used to say, ‘If I can put a single life on the path of God, I shall deem my work a great success.’ Certainly the number of persons whose thoughts turned Godwards because of his living example is large. A student who was with him at the Shanti Ashrama writes: ‘To think of Swami Turiyananda is an act of purification of the mind; to remember his life, an impulse to new endeavour.’

But to transform lives is not an easy task. Especially to change the outlook of those who are brought up in a different culture and tradition and are born with diverse tendencies of past lives is an arduous work. As such Swami Turiyananda had a very strenuous life at the Shanti Ashrama, so much so that his health broke down within a short period of two years.

Return to India

Swami Turiyananda badly required a change for his health. It was therefore decided that he should come to India at least for a visit, especially as he was very eager to see the leader—Swami Vivekananda. But before he reached Calcutta, the tragic news reached him that Swamiji had passed away. This news gave him such a great shock that a few days after he had arrived at Belur Math, he again started for North India to pass his days in tapasya. For about eight years he practised severe spiritual disciplines staying at various places like Vrindavan, Garhmukteswar in Bulandshahr district, Uttarkashi in Tehri State, and Nangal, some sixty miles below Hardwar. Except at Vrindavan, he lived alone and begged his food, though his health was indifferent and he needed help. A brahmacharin went to serve him at Nangal, but he would not allow him to do so, saying, ‘Ganga-water is my medicine, and Narayana is my doctor.’ He realised this idea so tangibly in his life that he felt absolutely no necessity for any other help and care. Afterwards he used to say that when he was unwell at Nangal, at first he made a deliberate effort to live to the above principle, but soon it became quite natural with him. While at Vrindavan, he was joined by Swami Brahmananda, the then President of the Ramakrishna Mission who had taken temporary leave from work for tapasya, and they both lived together performing intense spiritual practices.

After coming from America, he no longer engaged himself in any active work, excepting that with the cooperation of Swami Shivananda he built an Ashrama at Almora. Even there, the Ashrama grew as a by-product, as they stayed there only to perform tapasya.

As a result of severe austerities, his health was being undermined. But still he would not desist. His motto was, ‘Let pain and body look to themselves, but you, my mind, rest in the contemplation of God.’ About the year 1911 he developed symptoms of diabetes, which began to increase with the lapse of years. As a result of this, he got a carbuncle on his back, for which he had to be operated several times. Strange to say, in none of the operations did he allow himself to be under chloroform; and the surgeons themselves wondered at such a thing. He had the wonderful capacity to dissociate his mind from the body-idea, and so he did not feel the necessity for any chloroform. But he also had extraordinary fortitude as well as living faith in God; so it was easy for him to bear any amount of bodily suffering. Once, when he had an eye-complaint, nitric acid was applied to one of his eyes through mistake. When the mistake was found out and everybody got alarmed, he simply smiled and said, ‘It is the will of the Mother.’ Fortunately the eye was saved.

Mahasamadhi

The last three and a half years of his life he stayed at the Ramakrishna Mission Sevashrama at Varanasi, where he passed away on 21 July 1922. His death was as wonderful as his life was exemplary. The day before his passing, the Swami said all of a sudden, ‘Tomorrow is the last day. Tomorrow is the last day.’ But none could realise the meaning of these words just then. Next morning when Swami Akhandananda came to see him, Hari Maharaj said to him, ‘We belong to the Mother and the Mother is ours. Repeat, repeat.’ This he himself repeated a number of times. He then made obeisance to the Divine Mother reciting the well-known mantra beginning with सर्वमङ्गलमाङ्गल्ये (salutation to the Divine Mother—the source of all beneficence and bliss). This he repeated in the noon and also in the afternoon. In the afternoon he insisted on being helped to sit in a meditation posture. But as his strength gave way he could not remain sitting; and much against his wishes he was forced to lie down in bed. Then he said: ‘The body is falling off—the Pranas are departing. Make the legs straight and raise my hands.’ The hands being raised, he joined the palms and made repeated salutations uttering the name of the Master. And then he suddenly spoke out as if realising Brahman in everything; ‘This creation is Truth (सत्यं). This world is Truth. All is Truth. Prana is established in Truth.’ Then he recited the Vedic Mantras, सत्यं ज्ञानं अनन्तं ब्रह्म | प्रज्ञानमानन्दं ब्रह्म | ~ He asked to have these repeated; and Swami Akhandananda recited them. Hearing this ultimate Truth of the Upanishads, the Swami said, ‘That is enough’, and entered into Mahasamadhi. It seemed as though he quietly passed into sleep. Not a sign of pain or distortion was visible on his person. His face became aglow with a divine beauty and an unspeakable blessedness. Those who witnessed the incident could not but come to the conclusion that life and death for such a soul were like going from one apartment to another. Swami Turiyananda began life with a firm belief in the utility of self-exertion, but ended in perfect resignation to the Divine will. His self-surrender was, however, no less dynamic than his early impetuosity to storm the citadel of God. These two attitudes may seem contradictory. But he himself explained how they are not. Birds fly about in the infinite sky on and on till they are tired and weary, then they sit on the mast of a ship for rest. The same is the case with a man who believes in self-exertion. He strives and strives, knocks and knocks, but with every striving his egotism receives a blow till at last it is completely smashed, and he realises that the Divine Mother is everything. But to reach that ultimate stage one must struggle sincerely and earnestly. There should be no self-deception in spiritual life. Because people forget that surrender to the Divine Will becomes identified with a drifting life of inertia in the case of many.

Once he experienced that the Divine Mother actually wiped off any trace of egotism in him. And he used to say, pointing to his heart, ‘The mother is wide awake here and not asleep.’ In the course of conversation he once gave out, ‘At one time I felt that every footstep of mine was through Her power and that I was nothing. I clearly felt this. This feeling lasted for some days.’

There was another aspect of his self-surrender to the Divine Mother. It made him absolutely free from any fear. People who talk glibly of Divine Will and all that are found, more often than not, to be timid and victims of false, if not hypocritical, humility. But the case was just the opposite with Hari Maharaj. He did not know what it was to fear. During the Terrorist Movement in Bengal the police were after many monks living in North India. Hari Maharaj was then at Dehradun. A police officer of high rank was after him incognito. Once he asked the Swami whether he was afraid of the police, as evidently some monks were. They were out for a walk. On hearing those words, the Swami at once halted, looked at the man behind and with eyes emitting fire as it were, said: ‘I do not fear even Death, why should I fear any human being? In the whole life I have done no crime, what reason have I to fear the police?’ The words were uttered with so much strength and firmness that the man looked small. He felt so much awed by the greatness of the personality that stood before him, that he touched the feet of the Swami and apologised. Afterwards he became an admirer and devotee of Hari Maharaj.

Even in the complete self-effacement of Swami Turiyananda before the Divine Mother, how energetic he was! He was a man of uncompromising attitude. Whatever he would do, he would apply the whole strength of his soul to it. One found him always sitting erect, even in his illness, even while on an easy chair, he would never bend his body. This simple physical characteristic represented, as it were, his mental attitude. He was unbending in not allowing Maya to catch him. In his self-exertion as well as in his self-surrender one would find a great spiritual force intensely active in him.

When he was in any of the Ashramas or Maths, he would hold classes or inspire people for a higher life through conversation. He was a great conversationalist. But his conversation was always full of great spiritual fervour. In it flowed quotations from the Gita, Upanishads, Tulsidas, Kabir, or Nanak as also from the Bible. Once asked as to how his conversation was so spontaneous and at the same time of a high level of spiritual quality, the Swami said, ‘Well, from my childhood I have lived that life intensely.’

Not a few received spiritual impetus in their lives through his letters. Not being able to be with him personally, these devout souls had correspondence with him regarding their spiritual difficulties. And the letters he wrote in reply would always wield a tremendous influence upon their lives. These letters indicate his clear thinking, vast scholarship, and more than that, his spiritual vision. Once asked as to how his answers to the questions became so effective, the Swami said: ‘There are two ways of answering a question—one is to answer from the intellect, the other is to answer from within. I always try to answer from within.’

Thus though not actively engaged in any philanthropic work, the life of Hari Maharaj was of tremendous influence to many. He had a remarkable breadth of vision. In him there was the synthesis of Jnana, Karma, Yoga, and Bhakti and many things more. That was perhaps the main reason why all classes of people were attracted to him. He greatly eulogised the Seva work as inaugurated by Swamiji. Though he himself spent his whole life in intense spiritual practices in the form of meditation and contemplation, he used to say, ‘If one serves the sick and the distressed in the right spirit, in one single day one can get the highest spiritual realisation.’ Even while in his very deathbed, he exhorted a monk with the words: ‘Don’t doubt. Do the work started by Swamiji in the right spirit. From that itself will come samadhi or any other supreme spiritual attainment. Have no doubt. Plunge headlong into work. Swamiji once told me, “Haribhai, I have chalked out a new path to God-realisation. So long people thought that salvation could be had only through prayer, meditation, and the like. But now my boys will attain the bliss of liberation-in-life by mere selfless work.” So have no doubt. It is his charge.’

He had a feeling heart. He felt for the masses of India and encouraged all forms of philanthropic work. He was in close touch with all current events, and took great interest in the movement started by Mahatma Gandhi, for in this he found the promise for the sunken millions of India.

His devotional side was very marked. He used to visit shrines as often as he could, and devotional songs always had a telling effect upon him. His chanting of sacred texts on special holy occasions was a thing to enjoy—such a devotional attitude and such perfect intonations one could seldom meet with.

We cannot do better than conclude this article in the Swami’s own words: ‘I have done what one, being born a man, should do. My aim was to make my life pure. I used to read a great deal, eight or nine hours daily. I read many Puranas and then Vedanta, and my mind settled on Vedanta. When I first read the verse in which it is said that life is meant for the realisation of Jivanmukti (freedom in this very life), I leapt in joy, for that indeed was the purpose of my life.’

Related Articles: