Early Life

At the time when Sri Ramakrishna was attracting devotees— old and young—to the temple-garden at Dakshineswar, a young man in his teens, belonging to a neighbouring family, used to visit the garden of Rani Rasmani. He had read of Sri Ramakrishna in the literature of the Brahmo Samaj; but his aristocracy and rural prejudice stood in the way of any personal acquaintance. One day he had a desire for a flower. A man was passing by. The boy took him for a gardener and asked him to pluck the flowers for him. The man obliged. Another day the boy saw many people seated in a room in front of that gardener and listening to his discourse. Was this then the Ramakrishna of whom Keshab wrote so eloquently? The boy went nearer but stood outside. At this time the Master asked someone to bring all those who were outside within the room. The man found only a boy and brought him inside and offered him a seat. When the conversation ended and all went away, the Master came to the boy and very lovingly made inquiries about him.

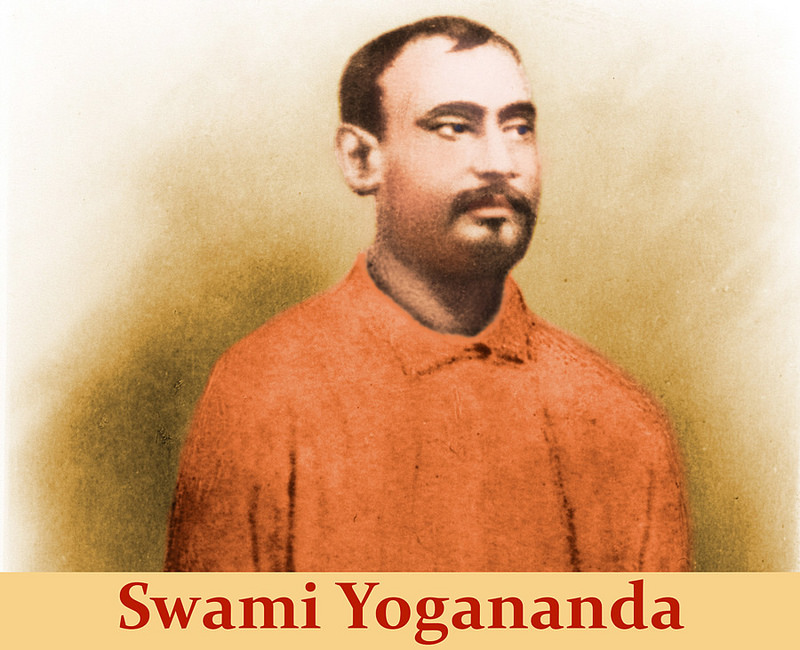

The name of the boy was Yogindra Nath Chaudhury. The Master was delighted to know that the boy was the son of Nabin Chandra Chaudhury, his old acquaintance. The Chaudhurys were once very aristocratic and prosperous, but Yogin’s parents had become poor. His father was a very orthodox brahmin and performed many religious festivals. Sri Ramakrishna, during the period of his spiritual striving, had sometimes attended these festivals, and was thus known to the family.

Yogin was born in the year 1861. From his boyhood he was of a contemplative temperament. Even while at play with his companions, he would suddenly grow pensive, stop play, and look listlessly at the azure sky. He would feel that he did not belong to this earth, that he had come from somewhere in some other plane of existence and that those who were near about him were not really his kith and kin. He was simple in his habits and never hankered after any luxury. He was a bit reserved and taciturn by nature. This prevented his friends from being very free with him. But he commanded love and even respect from all. After he was invested with the sacred thread, he spent much of his time in meditation and worship, in which he now and then became deeply absorbed.

Yogin was about sixteen or seventeen when he met Sri Ramakrishna for the first time. He was then studying for the Entrance Examination. At the very first meeting the Master recognized the spiritual potentiality of the boy and advised him to come to him now and then. Yogin was charmed with the warmth and cordiality with which he was received; and he began to repeat his visits as often as he could.

With Sri Ramakrishna

To the people of Dakshineswar Sri Ramakrishna was known as an ‘eccentric brahmin’. They had no idea that the ‘eccentricity’ in his behaviour was due to his God-realisation and disregard for this world. The orthodox section looked upon him with suspicion because of his seeming disregard for strict caste rules. Therefore, Yogin did not dare to come to him freely and openly, for he was afraid there would be objections from his parents if they knew about it. So he visited the Master stealthily.

But love, like murder, will out. Soon it was known that Yogin was very much devoted to Sri Ramakrishna and spent most of his time with him. Yogin’s friends and companions began to taunt and ridicule him for this. Of a quiet nature as he was, he met all opposition with a silent smile. His parents were perturbed to see him indifferent to his studies and so much under the influence of Sri Ramakrishna. But they did not like to interfere with him directly as they thought it would be of no avail.

Yogin thought that his continuance of studies was useless, for he had no worldly ambition. But just to help his parents, who were in straitened circumstances, he went to Kanpur in search of a job. He tried for a few months, but could not get any employment. So he devoted his ample leisure to meditation and spiritual practices. He shunned company and liked to live alone with his thoughts. He spoke as little as possible. His movements and behaviour were unusual. The uncle of Yogin with whom he stayed at Kanpur, got alarmed lest he should go out of his mind. He wrote to the father of Yogin all about him and suggested marriage as the only remedy; for that might create in him an interest in worldly things.

Things were arranged accordingly at home. Yogin knew nothing about this. He only got information that someone was ill at home, and thinking it might be his mother to whom he was greatly devoted, he hurried to Dakshineswar. But to his great dismay, he found that he had been trapped; all this was simply a pretext to bring him home for his marriage. He was in a great fix. He was against marriage, for that would interfere with his religious life. His great desire was to live a life of renunciation and devote all his time and energy to the realisation of God, but now there was a conspiracy to frustrate his noble resolve.

Yogin was too gentle to be able to resist the wishes of his parents—especially of his mother, and in spite of himself he consented to marry. His parents wrongly thought that marriage would wean his mind from other-worldliness. But the effect was just the reverse. The fact that his resolve of living a celibate life had been frustrated weighed so heavily on his mind that he felt miserable over it. He became moody and brooded day and night over his mistake. He did not even like to show his face to the Master, who had high expectations about his spiritual future and would be sorely disappointed to learn that he had falsified all his hopes through a momentary weakness.

When the news of all that had happened with regard to his beloved Yogin reached the Master, he sent information again and again to Yogin to come and see him. But Yogin was reluctant to go. Thereupon the Master hit upon a plan to drag him in, and told a friend of Yogin: ‘Yogin once took some money from here (that is, from a temple officer). It is strange that he has not returned the money, nor has he given any account of that!’ When Yogin heard of this, his feelings were greatly wounded. He remembered that a temple official had given him a small sum to make some purchases for him before he left for Kanpur, and a small balance of that remained. But because of his marriage he had felt ashamed to go to the temple and therefore could not return the unspent money. At the remarks of the Master, however, he was so aggrieved that he resolved to take the earliest opportunity to return the money and at the same time he thought that it would be his last visit to him.

Sri Ramakrishna was seated on his cot with his loin-cloth on his lap when Yogin came to see him. Putting his cloth under his arm, he ran like a child to receive Yogin as soon as he saw him. Beside himself with joy at the coming of Yogin, the first thing that the Master said to him was: ‘What harm if you have married? Marriage will never be an obstacle to your spiritual life. Hundreds of marriages will never interfere with your spiritual progress if God is gracious. One day bring your wife here. I shall so change her mind that instead of an obstacle she will be a great help to you.’

A dead weight was lifted, as it were, from Yogin’s heart, as he heard the Master utter these bold and encouraging words in an ecstatic mood. He saw light where it had been all darkness for him. He was filled with new hope and strength. While taking leave of the Master a little later, he raised the topic of the balance of the money which he was to return, but to this the Master was supremely indifferent. He understood that the earlier remarks about the money had simply been an excuse to bring him there. Now his love and admiration for the Master became all the more great, and he began to repeat his visits.

Even after marriage Yogin was indifferent to worldly affairs just as before. This was a great disappointment to his parents who had thought of binding him to the world through the tie of wedlock. Once Yogin’s mother rebuked him for his growing detachment to the world as unbecoming of one who had a wife to support. He was greatly shocked. Did he not marry only at the earnest importunity of his mother! From this time on, his aversion for worldly life increased all the more. He thought the Master was the only person who consistently and most selflessly loved him. And he began to spend greater time with him. The Master also found an opportunity to pay greater attention to the training of Yogin.

We have said that Yogin was very soft-natured. It was difficult for him to hurt even an insect. But sometimes too much gentleness becomes a source of trouble rather than a virtue. Sri Ramakrishna noticed this unreasonable softness in the character of Yogin, and he wanted to set this right. He once noticed that there were some cockroaches in his bundle of clothes and asked Yogin to take the bundle outside the room and kill the insects. Yogin took the clothes outside the room. But as he was too gentle to kill the insects, he simply threw them away, hoping that the Master would not follow up the matter. But strangely enough he did inquire whether the cockroaches had been killed. When the answer was in the negative, Sri Ramakrishna gave him a mild reproof, for not obeying his words in toto.

A similar incident happened on another day. Yogin was going from Calcutta to Dakshineswar by a country boat in which there were other passengers as well. One of them began to criticize Sri Ramakrishna as being a hypocrite and so on. Yogin felt hurt at such remarks, but did not utter even a word of protest. The Master needed no defence from Yogin: he was tall enough to be above the reach of any cynicism of fools—Yogin thought. When after coming to Dakshineswar he narrated the incident to Sri Ramakrishna, thinking that the Master would approve of his goodness in not opposing the passengers, the reaction was just the opposite. He took him to task for pocketing the blasphemy heaped upon the guru. ‘A disciple should never hear criticisms hurled against his guru’, said he. ‘If he cannot protest, he should leave the spot forthwith.’

Once Yogin went to the market to make some purchases for the Master. The cunning shopkeeper feigned to be very religious- minded and Yogin took him to be such. But when he returned to Dakshineswar, he found that the shopkeeper had cheated him. This called for a sharp rebuke from the Master. ‘A man may aspire to be religious; but that is no reason why he should be a fool’, said Sri Ramakrishna by way of correcting him.

Though Yogin trusted a man easily and had the simplicity of a child, he was not a simpleton. Rather, he had a keen discriminating mind and was critical in his outlook. But his critical attitude once led him into a quandary. One night he slept in the same room with the Master, but when he woke up in the dead of night he missed him and saw that the door was open. At first he felt curious, then he became suspicious as to where he could have gone at such an unearthly hour. He came outside, but Sri Ramakrishna could not be seen. Did he then go to his wife who was staying at the concert house just opposite?—Yogin thought. Then Sri Ramakrishna was not what he himself professed to be! He wanted to probe into the mystery, and stood near the concert-house to see if he came out of the room. After some time Sri Ramakrishna came from the Panchavati side and was surprised to see Yogin standing near the concert-house. Yogin was stupefied and felt ashamed of himself for his suspicion. A more sinful act could never be conceived of—to suspect even in thought the purity of a saint like Sri Ramakrishna! The Master understood the whole situation and said encouragingly, ‘Yes, one should observe a sadhu by day as well as at night.’ With these words he returned to his room, followed mutely by Yogin. In spite of these sweet words, Yogin had no sleep throughout the rest of the night, and later throughout his whole life he did not forgive himself for what he considered to be an extremely sinful act.

There are many incidents to show that Yogin, with all his devotion to the Master, kept his critical faculty alert and did not fail to test him in case of a doubt. Once he asked the Master how one could get rid of the sex-idea. When Sri Ramakrishna said that it could be easily done by prayer to God, this simple process did not appeal to him. He thought that there were so many persons who prayed to God, but nevertheless there came no change in their lives. He had expected to learn from the Master some yogic practice, but he was disappointed, and came to the conclusion that this prescription of a simple remedy was the outcome of his ignorance of any other better means. During that time there stayed at Dakshineswar a Hatha yogi who would show to visitors his dexterity in many yogic feats. Yogin got interested in him. Once he came to the temple precincts and without meeting the Master went straight to the Hatha yogi where he sat listening to his words spellbound. Exactly at that moment the Master chanced to come to that place. Seeing Yogin there, he very endearingly caught hold of his arms and while leading him towards his own room said, ‘Why did you go there? If you practise these yogic exercises, your whole thought will be concentrated on the body and not on God.’ Yogin was not the person to submit so easily. He thought within himself, perhaps the Master was jealous of the Hatha yogi and was afraid lest his allegiance be transferred to the latter. He always thought himself to be very clever. But on second thoughts he tried the remedy suggested by the Master. To his great surprise he found wonderful results and felt ashamed of his doubting mind. Afterwards Swami Vivekananda used to say, ‘If there is any one amongst us who is completely free from sex-idea, it is Yogin.’

To recount another incident of a similar type: Once he found that the Master was very much perturbed over the fact that his share of the consecrated food of the temple had not been sent to him. Usually the cashier of the temple would distribute the food offered in the temple after the worship had been finished. Being impatient Sri Ramakrishna sent a messenger to the cashier and afterwards himself went to him to inquire about the matter. Yogin was proud of his aristocratic birth. When he saw the Master agitated over such a trifle, he thought that he might be a great saint, but still his anxiety at missing the consecrated food was the result of his family tradition and influence—being born in a poor priest-family, he was naturally particular about such insignificant things. When Yogin was thinking in this way, the Master came and of his own accord explained, ‘Rani Rasmani arranged that the consecrated food should be distributed amongst holy men. Thereby she will acquire some merit. But these officers, without considering that fact, give away the offerings at the temple to their friends and sometimes even to undesirable persons. So I am particular to see that the pious desire of that noble lady is fulfilled.’ When Yogin heard this, he was amazed to see that even an insignificant act of the Master was not without deep meaning, and he cursed himself for the opinion he had formed.

Yogin grew spiritually under the keen care of the Master. Afterwards when Sri Ramakrishna fell ill and was under medical treatment at Cossipore, he was one of those disciples who laboured day and night in attending to the needs and comfort of their beloved Master. Long strain on this account told upon the none too strong health of Yogin, but the devoted disciple worked undauntedly.

It soon became apparent that no amount of care on the part of the disciples could arrest the progress of the Master’s disease. His life was despaired of. One day he called Yogin and asked him to read out to him a certain portion of the Bengali almanac, date by date. When Yogin had reached a certain date and read it Sri Ramakrishna told him to stop. It was the date on which the Master passed away.

Austerity and Pilgrimages

The Mahasamadhi of Sri Ramakrishna threw all into deep gloom. To recover from this shock the Holy Mother went to Vrindavan with Yogin, Kali, Latu, Golap-Ma, Lakshmi Devi, and Nikunja Devi (wife of ‘M’). At the end of a year the Holy Mother returned to Calcutta. After staying there for a fortnight, Yogin, who had now become Swami Yogananda, escorted the Holy Mother to Kamarpukur, from where he went out for tapasya. When in the middle of 1888 the Holy Mother came to live in Nilambar Babu’s garden-house at Belur, Swami Yogananda also returned to attend on her. His service to the Holy Mother was wonderful. In looking after the comfort of the Holy Mother, he threw all personal considerations to the wind. For, did he not see the living presence of the Master in her? Then, to serve her with all devotion and care, he thought, was his best religion. Whenever the Holy Mother left her village-home for other places Swami Yogananda used to be on attendance almost invariably. Thus in November 1888 he was with her at Puri, where along with Swami Brahmananda and others they stayed till the beginning of the next year. It is definitely known that he was with her at Ghushuri, near Belur, in 1890, at Nilambar Babu’s house at Belur in 1893, at Kailwar in 1894, at a rented house at Sarkarbari Lane, Calcutta, in 1896, and at another rented house at Bosepara Lane, Calcutta, in 1897. Most of the intermediate periods of the early years he spent in tapasya at various places till his health compelled him to give up the practice and stay permanently in Calcutta.

It is not possible to give a full account of his days of spiritual practice; for not much has been preserved. Some time in 1891, he went to Varanasi where he lived in a solitary garden-house absorbed in spiritual practices. It is said that during this period he would grudge the time he spent even for taking meals. He would beg some day pieces of bread for his food and for the following three or four days these pieces, soaked in water, would constitute his only meal. During this time there was a great riot in Varanasi, but he commanded such respect in the vicinity that rioters of both sides would not even disturb him. But the hardship which he was undergoing was too much for his constitution, which broke down completely. He never regained his normal health. From Varanasi he returned to the Math at Baranagore. He was still ailing. But his bright, smiling face belied his illness. Who could imagine that he was ill when he would be seen engaged wholeheartedly in fun and merry-making with his beloved brother disciples!

When the Holy Mother came to Calcutta, Swami Yogananda again became her attendant. He spent about a year in devoted service to the Holy Mother. After that he stayed chiefly at the house of Balaram Bose in Calcutta. He was now a permanently sick person—a victim of intestinal ailments. But he was the source of much attraction. So great was his amiability that whoever would come into contact with him would be charmed with him. One would at once feel at home with him. Some young men who got the opportunity of mixing with him at this time afterwards joined the Ramakrishna Order and became monks.

From 1895 to 1897 Swami Yogananda organized public celebrations of the birth anniversary of Sri Ramakrishna on a large scale at Dakshineswar. And in 1898 he organized a similar celebration at Belur. The success of these celebrations, against tremendous odds, was due to the great influence Swami Yogananda had over men—especially of the younger generation. The organizing ability of Swami Yogananda was also evidenced when a grand reception was given to Swami Vivekananda in 1897 on his return from America. Swami Yogananda was the moving spirit behind it.

When Swami Vivekananda (Swamiji), after his return from the West, told his brother disciples about his proposal to start an organization, Swami Yogananda was the person to raise a protest. His contention was that Sri Ramakrishna wanted all to devote their time and energy exclusively to spiritual practices, but that Swamiji, deviating from the Master’s teachings, was starting an organization on his own initiative. This provoked the great Swami too much and made him unconsciously reveal a part of his inner life. Swamiji feelingly said that he was too insignificant to improve upon the teachings of that spiritual giant— Sri Ramakrishna. If Sri Ramakrishna wanted he could create hundreds of Vivekanandas from a handful of dust, but that he had made Swamiji simply a tool for carrying out his mission, and Swami Vivekananda had no will but that of the Master. Such astounding faith had the effect of winning over Swami Yogananda immediately. When the Ramakrishna Mission Society was actually started, Swami Yogananda became its Vice president.

This was not the only occasion when Swami Yogananda showed the power of individual judgement and of a great critical faculty by challenging the very leader—Swami Vivekananda, though his love for the latter was very, very deep. Indeed, one who dared examine the conduct of his guru with a critical eye before fully submitting to him, could not spare his gurubhai (brother disciple). Two years after the incident referred to above, Swami Vivekananda was accused again by some of his gurubhais of not preaching the ideas of their Master who had insisted on bhakti and on spiritual practices for the realisation of God, whereas Swami Vivekananda constantly urged them to go about working, preaching, and serving the poor and the diseased. Here also Swami Yogananda started the discussion. At first the discussion began in a light-hearted mood on both sides. But gradually Swami Vivekananda became serious, till at last he was choked with emotion and found visibly contending with his love for the poor and his reverence for the guru. Tears filled his eyes and his whole frame began to shake. In order to hide his feelings he left the spot immediately. But the atmosphere was so tense that none dared break the silence even after Swamiji had left. A few minutes later some of the gurubhais went to his apartment and found him sitting in meditation, his whole frame stiff and tears flowing from his half-closed eyes. It was nearly an hour before Swamiji returned to his waiting friends in the sitting room, and when he began to talk, all found that his love for the Master was much deeper than what could be seen from a superficial view. But he was not allowed to talk on that subject. Swami Yogananda and others took him away from the room to divert his thoughts.

Swami Yogananda commanded respect for his sterling saintly qualities. But what distinguished him among the disciples of the Master was his devoted service to the Holy Mother. He was one of the early monks who discovered the extraordinary spiritual greatness of the Holy Mother, hidden under her rural simplicity of manners. This conviction led to an unquestioning dedication to her cause. He looked to her comfort in every way. If by chance a few coins were offered to him by somebody, he preserved these for the Mother’s use. He considered no sacrifice too great for her.

When Swami Yogananda became too weak to attend to all the works of the Holy Mother, a young monk (later known as Swami Dhirananda) was taken as his assistant. When the Holy Mother was in Calcutta, naturally many ladies would flock to her. Seeing the situation, Swami Vivekananda once took Swami Yogananda to task for keeping a young brahmacharin as his assistant. For, if the celibate life of the latter was endangered, who would be responsible? ‘I’, came the immediate reply from Swami Yogananda, ‘I am ready to sacrifice my all for him.’ The words were uttered with so much sincerity and earnestness that everyone who heard them could not but admire the largeheartedness of Swami Yogananda.

Mahasamadhi

Swami Yogananda’s health was becoming worse every day, and his suffering soon came to an end. On 28 March 1899, he passed away. He was the first among the monastic disciples of the Master to enter Mahasamadhi. The blessed words that he uttered before death were: ‘My Jnana and Bhakti have increased so much that I cannot express them.’ An old sannyasin brother who was at the bedside at the solemn moment said that they felt all of a sudden such an inflow of a higher state of being, that they vividly realised that the soul was passing to a higher, freer, and superior state of consciousness than the bodily state. Swami Vivekananda was greatly moved at the passing away of Swami Yogananda and very feelingly remarked, ‘This is the beginning of the end.’ The Holy Mother also said: ‘That’s like a brick falling out of the wall of a building; it is an evil omen.’ She cherished his memory affectionately for ever.

Outwardly the life of Swami Yogananda was uneventful. It is very difficult to give or find out details through which one can see his personality. Only those who moved with him closely could see something of his spiritual eminence. One of the younger members of the Math at that time wrote with regard to him: ‘He was such a great saint that it fills one with awe to belong, even as the youngest member, to the Order that contained him.’ Swami Yogananda commanded great love and respect from all the lay and monastic disciples of the Ramakrishna Order. He was one of those whom the Master spotted out as ‘Ishwarakotis’ or ‘eternally perfect’— one of the souls which are never in bondage but now and then come to this world of ours for guiding humanity Godwards.