(Reminiscences: a Meeting With ‘M.’)

In 1913 I matriculated and won a scholarship, getting high marks in Sanskrit and mathematics. But to come to the first impact of Grace which booned me with faith through the agency of a cousin I came to idolize! His name was Nirmalendu. I called him Nirmalda, the suffix da denoting elder brother. . .

…Nirmalda was an authentic devotee… As I came to know him more I was delighted to discover that he had the gift also to communicate the light which his father had lit in his heart. Besides, he was an ardent worshipper of Sri Ramakrishna—so much so that his eyes used to glisten when he talked eloquently of the Mother Kali coming in person to Sri Ramakrishna. But though I was a believer at heart I found this a little difficult to accept. No wonder, for, in our milieu I had heard my father’s intellectual friends laugh at this tall claim of Sri Ramakrishna. They challenged: ‘How could the Infinite Divine assume a human form and speak to His devotees in a human tongue?’ ‘God may indeed exist,’ they judicially conceded, ‘but how could He possibly accept human limitations?. . .’

Nevertheless my malaise continued or rather visited me from time to time till Nirmalda enjoined me to read Ramakrishna Kathamrita [The Gospel of Sri Ramakrishna]. ‘Don’t argue from ignorance, my pathetic sage,’ he bantered. ‘Be humble and pray for light to repeal the darkness that makes you believe that croaking with reason is more rewarding than singing in rapture…’

But though Sri Ramakrishna’s words induced in me the will to faith, for the time being the net result was vacillation: to believe or not to believe, to welcome or to reject, to aspire to the epiphany or accept it only tentatively? After a good deal of wavering, I decided to ‘wait and see’. . .

I still recall how Nirmalda upbraided me one day for my hesitation to accept Sri Ramakrishna’s testimony. ‘But how can you take me to task,’ I complained, ‘when his statements were not written by him, but merely attested to by one of his disciples?

How can one be sure that ‘Sri Ma’ [‘M.’] was a faithful reporter? Surely you don’t claim that he used to keep a record of it all, in detail, in a diary from day to day?’

Nirmalda leaped up and roared: ‘That is exactly what he did, you sceptic! Come, I will take you straight to him and prove it to the hilt.’

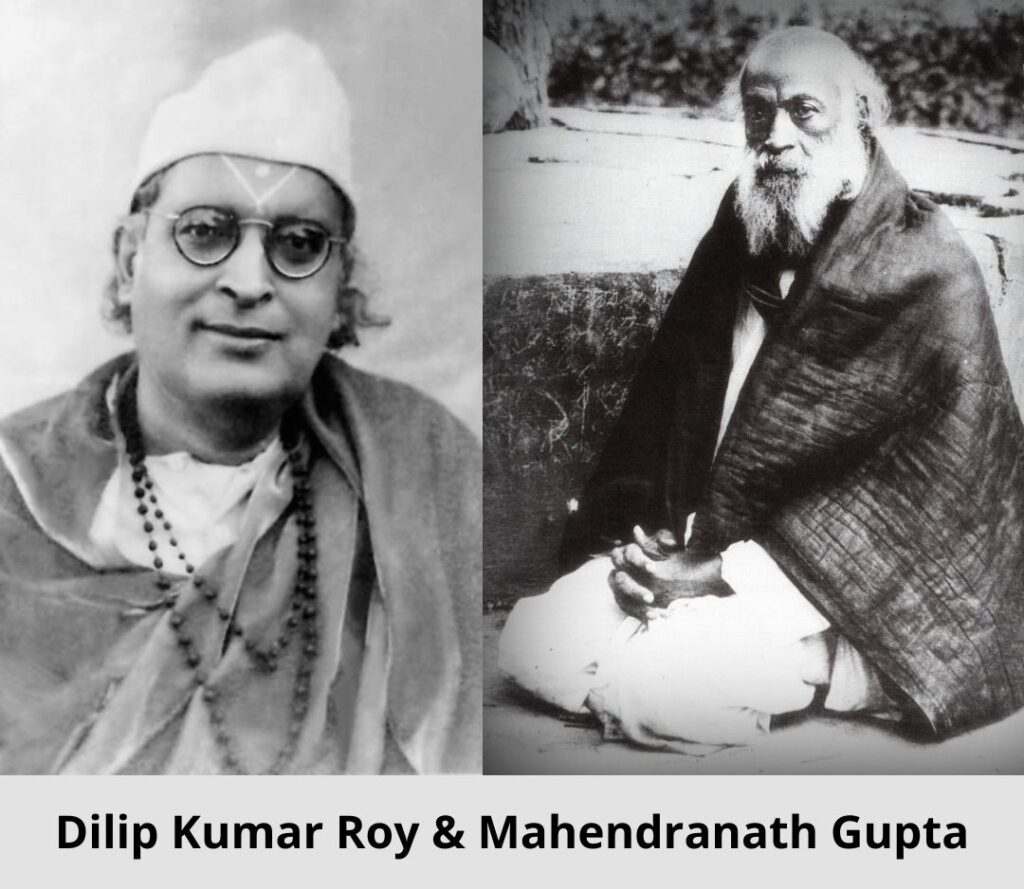

I have mentioned already that ‘Sri Ma’ was the pseudonym of Sri Mahendra Nath Gupta, a favourite disciple of the Messiah. He was the headmaster of a very good school, Morton Institution. I had heard of him and, naturally, my curiosity often goaded me to try to meet him face to face, although when Nirmalda invited me to accompany him to the great chronicler I felt not a little shy. But Nirmalda dragged me into his presence—a willing prisoner in whose heart joy vied with alarm for mastery. Lo, to meet ‘Sri Ma,’ an intimate of Sri Ramakrishna! Joy, joy, joy! But how could I stand before him without withering away! A deep fear gripped me.

But ‘Sri Ma’ was not in the least formidable: he was compassion itself. What beautiful eyes, large and expressive, what a light on his face and last, though not least, what a childlike smile which made him despite his beard look so young and eminently approachable!

After my friend had bowed down to the ground at his feet and I followed suit, he asked me kindly who I was. I told him.

‘Oh, you are the great D.L. Roy’s son!’ he exclaimed. ‘Blessed, blessed boy, to have such a noble father! Come, come! Don’t be shy, draw nearer, come, sit here, close to me.’ He caressed my face with his hand, appraising me with an affectionate scrutiny.

I was delighted, my misgivings just conjured away. I sat beside him with bowed head, my heart going pit-a-pat.

After a while he placed his hand on my shoulder and asked: ‘Now tell me, my boy, what has made you call on me?’

I met his kindly eyes and answered: ‘I have come, sir, to hear about Thakur’—meaning Sri Ramakrishna.

He was galvanized and shouted: ‘Prabhash! Prabhash! (a relative of M) Just come, come running! Look, this little boy has come to hear from me about Thakur, fancy that!’ Then turning to me: ‘Look, my dear boy, how my hair has stood on end!’ And I looked in amazement: his body was indeed shivering with ecstasy and every single hair on his hand stood on end while his eyes glistened with unshed tears!

‘What devotion for the guru!’ I said, thrilled, to myself. I touched his feet with my forehead. He gathered me up tenderly.

‘You are blessed, my boy! Thrice blessed to have been called by Thakur’s Grace!’

Then he talked and talked about Sri Ramakrishna, laying stress on his Love Divine and relating incidents about his purity and simplicity which no human being could boast. Thereafter he showed me his treasured diaries, bound in morocco, wherein lay recorded for all time the ‘nectarous words’ of one who had come to appease the age-long thirst of countless way-lost mortals.

I was simply overwhelmed. For such a great devotee to have come down to the level of an unknown teenager and speak to him of his great guru’s divinity! For, to him, as to millions of other devotees in India and abroad, Sri Ramakrishna was and is still looked upon as an incarnation of Love Divine and immaculate purity. He pointed to a framed picture on the wall, an enlarged photograph of the Master, and said: ‘Look, it was taken by a devotee when he was in Samadhi. When, the next day, it was shown to Thakur he smiled and said: “A day will come when this picture will be worshipped by millions.” Now tell me, wasn’t he a prophet?’

My eyes filled. He drew me to him and then startled me by an unexpected remark.

‘Before you go, my boy,’ he said, ‘I would like to make you one request.’

Request! I stared at him in blank amazement.

‘You are born blessed in having such a great father,’ he went on. ‘Promise me you’ll keep a record of his jewelled sayings, will you?’ I nodded mechanically, still dumb-founded. He appraised me with his glistening eyes and amended: ‘And not only your father’s sayings. Whenever you meet a great man, you must put on paper any memorable words that fall from his lips. You had best keep a diary, as I have.’

I do not know what impelled him to make such a strange request to a mere schoolboy. Can it be that one hero-worshipper knows another? Or had he felt something, some intimation from above? I cannot tell. All I know is that I have never been able to forget my promise to him, which is the genesis of my book Among the Great, and later my Bengali reminiscences, entitled Smriticharan, in which I recorded my conversations with more than a dozen remarkable men whose contact had enriched my life.

The unexpected encouragement of ‘Sri Ma’ not only thrilled me, it effectively changed the course of my destiny in that I was oriented toward a new call that haunted me. Before I met him I had been quite a normal boy, a trifle precocious maybe—and as such more enthusiastic about whatever I came to love—but after my joyous contact with him I went on dreaming about him now and again and woke up often in a rapture. Nirmalda, who slept on a bed next to mine, sometimes awoke to find me praying with folded hands.

He had, indeed, somewhat unconsciously, become my guardian or, shall I say, torchbearer on this path. I was a proud boy but as I adored him I did not mind his hectoring me even when I was restless or somewhat disgruntled. One reason was that he introduced me to a good many sadhus of the Ramakrishna mission, notably Swami Saradananda, the famous author of the Messiah’s monumental biography which I read again and again in great joy. I read eagerly two other biographies also of Sri Ramakrishna—one by Ramchandra Dutta, the other by Gurudas Burman—and a few books of Swami Vivekananda, the more assiduously as Nirmalda was well-read in the Ramakrishna Mission literature and I could not bear to lag behind.

But what enraptured me was Sri Ramakrishna’s living room at Dakshineswar, in the famous Kali Temple of Rani Rasmani, situated on the holy River Ganga. The temple was sixteen miles from Calcutta, and as there were no buses or cars in those days (1910-11), we either had to take the train and then trudge two or three miles or go by boat. But these difficulties of transit did not discourage us—for we two fared to the Holy of Holies on winged feet, and the moment I entered his sanctum sanctorum I felt a deep heave in my heart and tears of ecstasy leaped to my eyes. I prayed and prayed in simple faith, the faith of a guileless boy, that I might follow in his footsteps, remain a brahmachari (celibate) and dedicate my life to the quest of Krishna and Kali. To me both were one, as I have said already.

Sources:

- 📗Pilgrims of the Stars—Autobiography of Two Yogis, by Dilip Kumar Roy and Indira Devi

- Vedanta Kesari Sep 2006