Pali text, illustration and English translation of Dhammapada verse 404:

asaṃsaṭṭhaṃ gahaṭṭhehi anāgārehi cū’bhayaṃ |

anokāsariṃ appicchaṃ tamahaṃ brūmi brāhmaṇaṃ || 404 ||

404. Aloof alike from laity and those gone forth to homelessness, who wanders with no home or wish, that one I call a Brahmin True.

The Story of The Monk and the Goddess

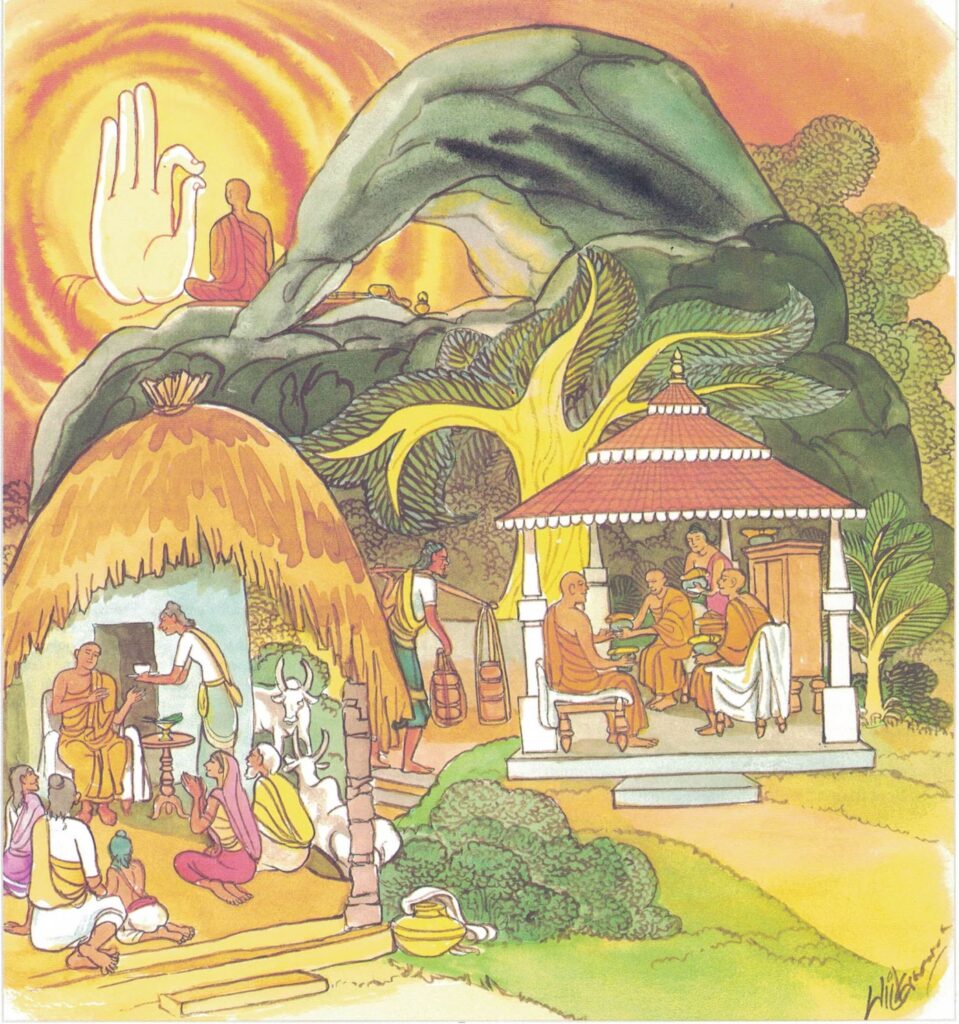

This verse was spoken by the Buddha while He was in residence at Jetavana, with reference to Venerable Tissa who dwelt in a mountain cave–Pabbhāravāsī Tissa Thera.

Monk Tissa, after taking a subject of meditation, went to a mountainside. There he found a cave which suited him and he spent the three months of the rainy season in that cave. He went to the village for alms-food every morning. In the village, there was a certain elderly woman who regularly offered him alms-food. In the cave there also lived a guardian spirit. As Tissa was one whose practice of morality was pure, she found it difficult to remain in the same cave, as he was a noble monk. At the same time, she did not have the courage to ask him to leave the place. So she thought of a plan that would enable her to find fault with the monk and thus cause him to leave the cave.

The spirit decided to possess the youngest son of the woman to whose house Tissa usually went for his alms-food. She caused the boy to behave in a peculiar way, turning his head backwards, and rolling his wide open eyes. When the woman saw what had happened, she screamed and the spirit said, “I have possessed your son. Let your monk wash his feet with water and sprinkle that water on the head of your son. Only then will I release your son.” The next day, when the monk came to her house for alms-food, she did what was demanded by the spirit and the boy was left in peace. The spirit went back to the cave and waited at the entrance for the monk. When Tissa returned, she revealed herself and said, “I am the spirit guarding this cave, O’ you exorcist, don’t enter this cave.” The monk knew that he had lived a virtuous life from the day he had become a monk, so he replied that he had not broken the precept of abstaining from practicing exorcism or witchcraft. Then she accused Tissa of having treated the young boy possessed by a spirit at the house of the elderly woman. But the monk reflected that he had not practiced exorcism and realised that even the spirit could find no fault with him. That gave him a delightful satisfaction and happiness; he attained arahathood while standing at the entrance to the cave.

Since Tissa had now become an arahat, he told the spirit that she had wrongly accused a monk like him, whose virtue was pure and spotless, and also advised her not to cause further disturbances. Tissa continued to stay in the cave till the end of the vassa, and then he returned to the Jetavana Monastery. When he told the other monks about his encounter with the spirit, they asked him whether he had been angry with the spirit when he was forbidden to enter the cave. He answered in the negative. The other monks asked the Buddha, “Venerable Tissa claims he has no more anger. Is it true?” The Buddha replied, “Monks, Tissa is speaking the truth. He has indeed become an arahat; he is no longer attached to anyone; he has no reason to get angry with anyone.”

Explanatory Translation (Verse 404)

gahaṭṭhehi anāgārehi ca ūbhayaṃ asaṃsaṭṭhaṃ

ānokasāriṃ appicchaṃ taṃ ahaṃ brāhmanaṃ brūmi

gahaṭṭhehi: with laymen; anāgārehi: with those who have renounced the world; ca ūbhayaṃ [ūbhaya]: with both these groups of people; asaṃsaṭṭhaṃ [asaṃsaṭṭha]: establishing no contact; ānokasāriṃ [ānokasāri]: not given to ways of craving; appicchaṃ [appiccha]: contented with little; taṃ: him; ahaṃ: I; brāhmanaṃ brūmi: call a brāhamaṇa.

He does not establish extensive contact either with laymen or with the homeless. He is not attached to the way of life of the householder. He is contented with the bare minimum of needs. I call that kind of person a true brāhmaṇa.

Commentary and exegetical material (Verse 404)

In Buddhist literature there are numerous references to encounters between Buddhist monks and spirits of the forest and the wilderness. Forests and mountains were sought after by monks who followed the path of meditation to achieve liberation. In some of these encounters, spirits are recorded to have been quite hostile. The discourse entitled Karanīya Metta Sutta. The chant of loving-compassion was created by the Buddha as a means of bringing about rapport and harmony between men and spirits.