Pali text, illustration and English translation of Dhammapada verse 356-359:

tiṇadosāni khettāni rāgadosā ayaṃ pajā |

tasmā hi vītarāgesu dinnaṃ hoti mahapphalaṃ || 356 ||

tiṇadosāni khettāni dosadosā ayaṃ pajā |

tasmā hi vītadosesu dinnaṃ hoti mahapphalaṃ || 357 ||

tiṇadosāni khettāni mohadosā ayaṃ pajā |

tasmā hi vītamohesu dinnaṃ hoti mahapphalaṃ || 358 ||

tiṇadosāni khettāni icchādosā ayaṃ pajā |

tasmā hi vigaticchesu dinnaṃ hoti mahapphalaṃ || 359 ||

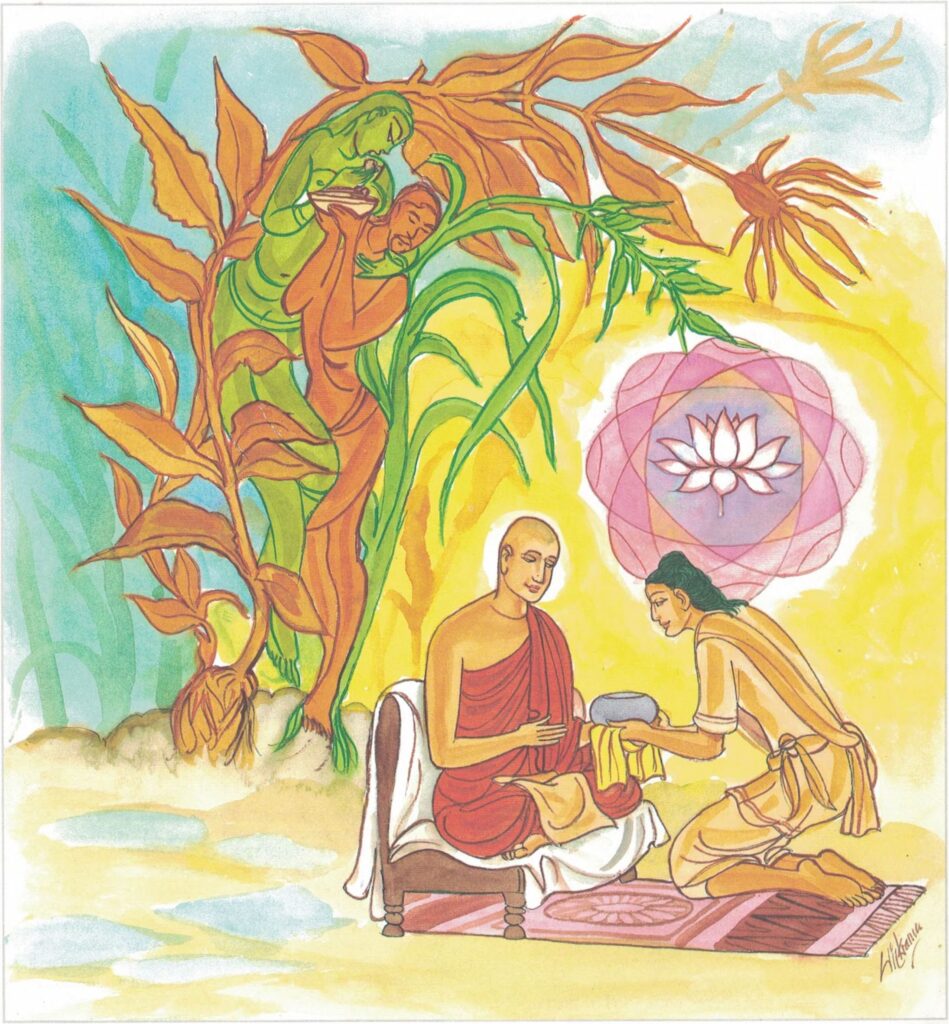

356. Weeds are a fault of fields, lust’s a human fault, thus offerings to the lustless bear abundant fruit.

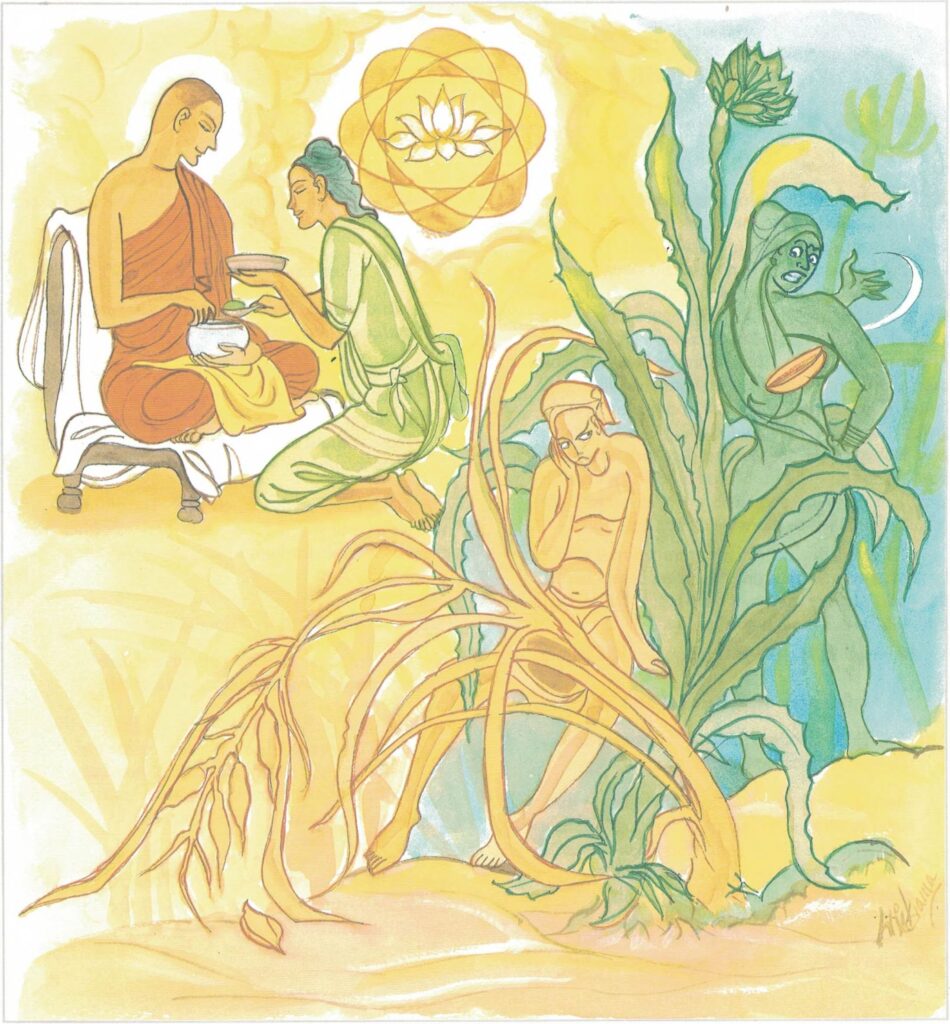

357. Weeds are a fault of fields, hate’s a human fault, hence offerings to the hateless bear abundant fruit.

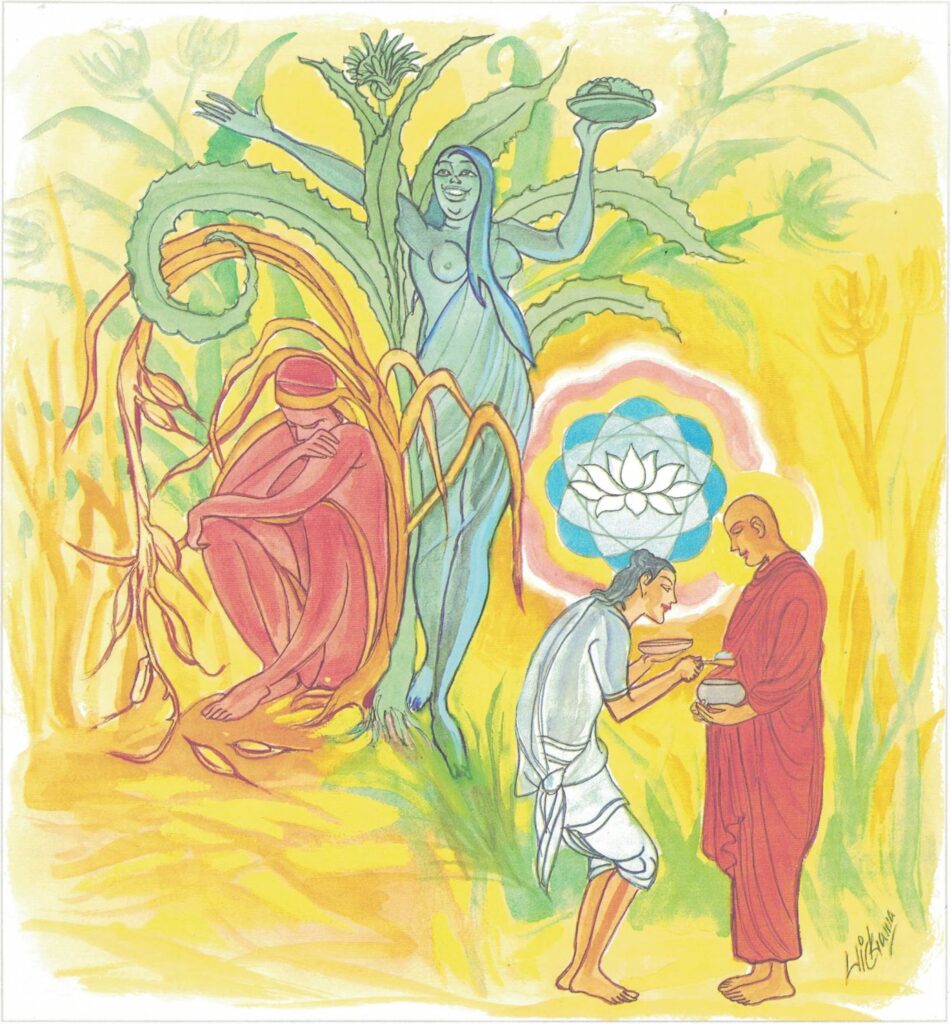

358. Weeds are a fault of fields, delusion, human’s fault, so gifts to the undeluded bear abundant fruit.

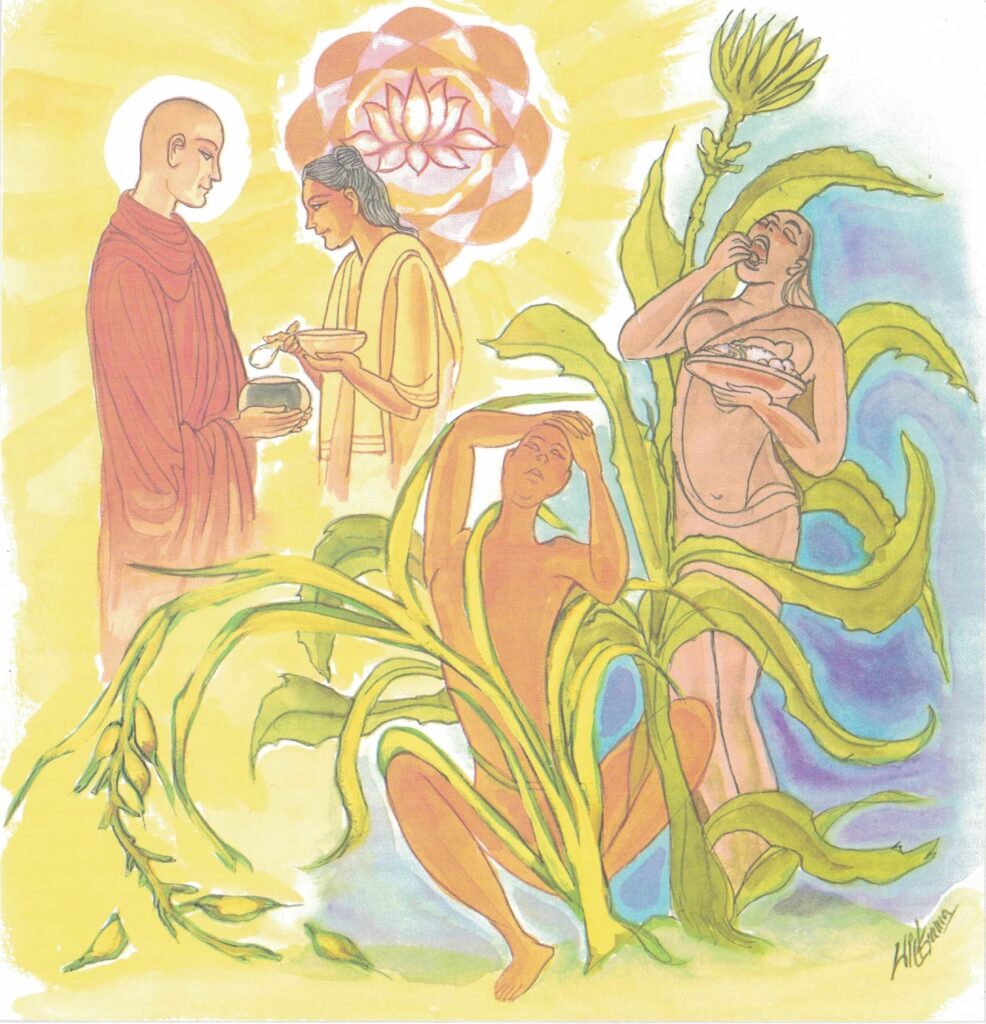

359. Weeds are a fault of fields, desire’s a human fault, so gifts to the desireless bear abundant fruit.

The Greater and the Lesser Gift

It is said that on a certain occasion, when the Venerable Anuruddha entered the village for alms, Indaka, a deva, gave him a spoonful of his own food. This was the good deed which he performed in a previous state of existence. Although Ankura had for ten thousand years set up a row of fire-places twelve leagues long and had given abundant alms, Indaka received a greater reward; therefore spoke Indaka thus. When he had thus spoken, the Buddha said, “Ankura, one should use discrimination in giving alms. Under such circumstances almsgiving, like seed sown on good soil, yields abundant fruit. But you have not so done; therefore your gifts have yielded no great fruit.” And to make this matter clear, he said, “Alms should always be given with discrimination. Alms so given yield abundant fruit.”

The giving of alms with discrimination is extolled by the happy one. Alms given to living beings here in the world who are worthy of offerings, yield abundant fruit, like seeds sown on good ground.

Having thus spoken, He expounded the Dhamma.

Explanatory Translation (Verse 356)

khettāni tiṇadosāni ayaṃ pajā rāgadosā

tasmā vītarāgesu dinnaṃ mahapphalaṃ hoti

khettāni: for fields; tiṇadosāni: the grass is the bane; ayaṃ pajā: these masses; rāgadosā: have passion as the bane; tasmā: therefore; vītarāgesu: to the passionless ones; dinnaṃ [dinna]: what is given; mahapphalaṃ hoti: will yield great results

Fields have weeds as their bane. The ordinary masses have passion as their bane. Therefore, high yields are possible only through what is given to the passionless ones.

Explanatory Translation (Verse 357)

khettāni tiṇadosāni ayaṃ pajā dosadosāni

tasmā vītadosā hi dinnaṃ mahapphalaṃ hoti

khettāni: for fields; tiṇadosāni: the grass is the bane; ayaṃ pajā: these masses; dosadosāni: have ill-will as the bane; tasmā: therefore; vītadosā: to those without ill-will; dinnaṃ [dinna]: what is given; mahapphalaṃ hoti: will yield great results

Fields have weeds as their bane. The ordinary masses have ill-will as their bane. Therefore, high yields are possible only through what is given to those without ill-will.

Explanatory Translation (Verse 358)

khettāni tiṇadosāni ayaṃ pajā mohadosā

tasmā hi vītamohesu dinnaṃ mahapphalaṃ hoti

khettāni: for fields; tiṇadosāni: the grass is the bane; ayaṃ pajā: these masses; mohadosā: have illusion as their bane; tasmā: therefore; vītamohesu: to the illusionless ones; dinnaṃ [dinna]: what is given; mahapphalaṃ hoti: will yield great results

Fields have weeds as their bane. The ordinary masses have illusion as their bane. Therefore, high yields are possible only through what is given to the one without illusion.

Explanatory Translation (Verse 359)

khettāni tiṇadosāni ayaṃ pajā icchādosā

tasmāhi vigaticchesu dinnaṃ mahapphalaṃ hoti

khettāni: for fields; tiṇadosāni: the grass is the bane; ayaṃ pajā: these masses; icchādosā: have greed as their bane; tasmā: therefore; vigaticchesu: to those devoid of greed; dinnaṃ [dinna]: what is given; mahapphalaṃ hoti: will yield great results

Fields have weeds as their bane. The ordinary masses have greed as their bane. Therefore, high yields are possible only through what is given to the one without greed.

Commentary and exegetical material (Verse 356-359)

In these verses, it is stated that high yields, in terms of merit, are possible only through what is given to those who are passionless, those who are without ill-will, those who are without illusion and those who are free of greed.

All these characteristics define Perfected Ones–arahats and those who are on their way to such achievement. Saints of this calibre are also described as Ariya-puggala (noble persons). Arahat, in Sanskrit, means the consummate one, the worthy one. This term arahat, applied exclusively to the Buddha and to His perfected disciples, was first used to describe the Buddha himself.

An arahat is one whose taints (āsava) are destroyed, who has lived the life, done what was to be done, laid down the burden, attained arahatship by stages, destroyed completely the bond of becoming, one who is free through knowing rightly. As his faculties have not been demolished, he experiences what is agreeable and disagreeable, he experiences pleasure and pain. The five aggregates remain. It is his extinction of lust, hate and delusion that is called the Nibbāna element with a basis remaining (saupādisesa nibbānadhātu).

The Buddha stated:

“And which, monks, is the Nibbāna element without a basis remaining (anupādisesa nibbānadhātu)?” “Here, monks, a monk is an arahat, one whose taints are destroyed, who has lived the life, done what was to be done, laid down the burden, attained arahatship by stages, destroyed completely the bond of becoming, one who is free through knowing rightly. All his feelings not being welcome, not being delighted in (anabhinanditāni), will here and now become cool: it is this, monks, that is called the Nibbāna element without a basis remaining.”

“These, monks, are the two Nibbāna elements.” This fact the Buddha declared:

Thus this is said:

These two Nibbāna elements are explained

By the Seeing One, steadfast and unattached:

When one element with basis belonging to this life

Remains, destroyed is that which to becoming leads;

When one without that basis manifests

In the hereafter, all becomings cease.The minds of those who know this conditioned state

Are delivered by destroying that to which becoming leads:

They realize the Dhamma’s essence and in stillness

Delighting, steadfast they abandon all becoming.

A being consists of the five aggregates or mind and matter. They change incessantly and are, therefore, impermanent. They come into being and pass away, for, whatever is of the nature of arising, all that is of the nature of ceasing.

Lust, hate and delusion in man bring about repeated existence, for it is said: Without abandoning lust, hate and delusion, one is not free from birth…

One attains arahatship, that is deliverance even while alive, by rooting out lust, hate and delusion. As stated above, this is known as the Nibbāna element with a basis remaining (saupādisesa nibbānadhātu). The arahat’s five aggregates or the remaining bases are conditioned by the lust, hate and delusion of his infinite past. As he still lives his aggregates function, he, therefore, experiences the pleasant as well as painful feelings that his sense faculties entertain through contact with sense objects. But, since he is freed from attachment, discrimination and the idea of selfhood, he is not moved by these feelings.

Now, when an arahat passes away, his aggregates, his remaining bases, cease to function; they break up at death; his feelings are no more, and because of his eradication of lust, hate and delusion, he is not reborn, and naturally, there is then no more entertaining of feelings; and, therefore, is it said: His feelings will become cool (sītibhavissanti).

The idea is expressed in the Udāna thus:

The body broke up, perception ceased,

All feelings cooled, all formations stilled,

Consciousness disappeared.

This is known as the Nibbāna element without a basis remaining (anupādisesa nibbānadhātu).

When a person totally eradicates the trio, lust, hate and delusion, that leads to becoming, he is liberated from the shackles of saṃsāra, from repeated existence. He is free in the full sense of the word. He no longer has any quality which will cause him to be reborn as a living being, because he has realized Nibbāna, the entire cessation of continuity and becoming (bhava-nirodha);he has transcended common or worldly activities and has raised himself to a state above the world while yet living in the world: His actions are issueless, are kammically ineffective, for they are not motivated by the trio, by the mental defilements (kilesa). He is immune to all evil, to all defilements of the heart. In him, there are no latent or underlying tendencies (anusaya); he is beyond good and evil, he has given up both good and bad; he is not worried by the past, the future, nor even the present. He clings to nothing in the world and so is not troubled. He is not perturbed by the vicissitudes of life. His mind is unshaken by contact with worldly contingencies; he is sorrowless, taintless and secure (asokaṃ, virajaṃ, khemaṃ).

Thus, Nibbāna is a ‘state’ realizable in this very life (diṭṭhadhammanibbāna). The thinker, the inquiring mind, will not find it difficult to understand this state, which can be postulated only of the arahat and not of any other being, either in this world or in the realms of heavenly enjoyment.

Though the sentient being experiences the unsatisfactory nature of life, and knows, at first hand, what suffering is, what defilements are, and what it is to crave, he does not know what the total extirpation of defilements is, because he has never experienced it. Should he do so, he will know, through self-realization, what it is to be without defilements, what Nibbāna or reality is, what true happiness is. The arahat speaks of Nibbāna with experience, and not by hearsay, but the arahat can never, by his realization, make others understand Nibbāna. One who has slaked his thirst knows the release he has gained, but he cannot explain this release to another. However much he may talk of it, others will not experience it; for it is self-experience, self-realization. Realization is personal to each individual. Each must eat and sleep for himself, and treat himself for his ailments; these are but daily requirements, how much more when it is concerned with man’s inner development, his deliverance of the mind.

What is difficult to grasp is the Nibbāna element without a basis remaining (anupādisesa-nibbāna), in other words, the parinibbāna or final passing away of the arahat.

An oft-quoted passage from the Udāna runs: Monks, there is the unborn, unoriginated, unmade and unconditioned. Were there not the unborn, unoriginated, unmade and unconditioned, there would be no escape for the born, originated, made and conditioned. Since there is the unborn, unoriginated, unmade and unconditioned, so there is escape for the born, originated, made and conditioned.

Here, there is neither the element of solidity (expansion), fluidity (cohesion), heat and motion, nor the sphere of infinite space, nor the sphere of infinite consciousness, nor the sphere of nothingness, nor the sphere of neither perception nor non-perception, neither this world nor the other, nor sun and moon. Here, there is none coming, none going, none existing, neither death nor birth. Without support, non-existing, without sense objects is this. This, indeed, is the end of suffering (dukkha).

Arahats are described also as ariya puggala or ariya (noble ones, noble persons).

The eight ariya puggalas are those who have realized one of the eight stages of holiness, i.e., the four supermundane paths (magga) and the four supermundane fruitions (phala) of these paths.

There are four pairs:

- the one realizing the path of stream-winning (sotāpatti-magga);

- the one realizing the fruition of stream-winning (sotāpatti phala);

- the one realizing the path of once-return (sakadāgāmi-magga);

- the one realizing the fruition of once-return (sakadāgāmi-phala);

- the one realizing the path of non-return (anāgāmi-magga);

- the one realizing the fruition of non-return (anāgāmi-phala);

- the one realizing the path of holiness (arahatta-magga) and

- the one realizing the fruition of holiness (arahatta-phala).

Summed up, there are four noble individuals (ariya-puggala); the stream-winner (sotāpanna); the once-returner (sakadāgāmi); the nonreturner (anāgāmi); the holy one (arahat).

According to the Abhidhamma, supermundane path, or simply path (magga), is a designation of the moment of entering into one of the four stages of holiness–Nibbāna being the object–produced by intuitional insight (vipassanā) into the impermanency, misery and impersonality of existence, flashing forth and forever transforming one’s life and nature.

By fruition (phala) are meant those moments of consciousness, which follow immediately thereafter as the result of the path, and which, in certain circumstances, may repeat for innumerable times during a lifetime.

(1) Through the path of stream-winning (sotāpatti-magga) one becomes free (whereas in realizing the fruition, one is free) from the first three fetters (samyojana) which bind beings to existence in the sensuous sphere, to wit: (i) personality-belief (sakkāya-diṭṭhi), (ii) skeptical doubt (vicikicchā), (iii) attachment to mere rules and rituals (silabbataparāmāsa).

(2) Through the path of once-returning (sakadāgāmi-magga) one becomes nearly free from the fourth and fifth fetters, to wit: (iv) sensuous craving (kāma-cchanda = kāma-rāga), (v) ill-will (vyāpāda = dosa).

(3) Through the path of non-returning (anāgāmi-magga) one becomes fully free from the above-mentioned five lower fetters.

(4) Through the path of holiness (arahatta-magga) one further becomes free from the five higher fetters, to wit: (vi) craving for fine-material existence (rūpa-rāga), (vii) craving for immaterial existence (arūpa-rāga), (viii) conceit (māna), (ix) restlessness (uddhacca), (x) ignorance (avijjā).

The stereotype sutta text runs as follows:

(1) After the disappearance of the three fetters, the monk has won the stream (to Nibbāna) and is no more subject to rebirth in lower worlds, is firmly established, destined for full enlightenment;

(2) After the disappearance of the three fetters and reduction of greed, hatred and delusion, he will return only once more; and having once more returned to this world, he will put an end to suffering;

(3) After the disappearance of the five fetters he appears in a higher world, and there, he reaches Nibbāna without ever returning from that world (to the sensuous sphere).

(4) Through the extinction of all cankers (āsava-kkhaya) he reaches already in this very life the deliverance of mind, the deliverance through wisdom, which is free from cankers, and which he himself has understood and realized.

The seven-fold grouping of the noble disciples is as follows:

- the faith-devotee (saddhānusāri),

- the faith-liberated one (saddhā-vimutta),

- the body-witness (kāya=sakkhī),

- the both-ways liberated one (ubhato-bhāga-vimutta),

- the Dhamma-devotee (dhammānusāri),

- the vision-attainer (diṭṭhi-ppatta),

- the wisdom-liberated one (paññā-vimutta).

These four stanzas extol the virtues of dāna, generosity.

Dāna is the first pāramī. It confers upon the giver double blessing of inhibiting immoral thoughts of selfishness, while developing pure thoughts of selflessness: It blesseth him that gives, him that takes.

A Bodhisatta is not concerned as to whether the recipient is truly in need or not, for his one object in practicing generosity, as he does, is to eliminate craving that lies dormant within himself. The joy of service, its attendant happiness, and the alleviation of suffering are other blessings of generosity.

In extending his love with supernormal generosity, he makes no distinction between one being and another, but he uses judicious discrimination in this generosity. If, for instance, a drunkard were to seek his help, and, if he were convinced that the drunkard would misuse his gift, the Bodhisatta, without hesitation, would refuse it, for such misplaced generosity would not constitute a pāramī.

Should anyone seek his help for a worthy purpose, then instead of assuming a forced air of dignity or making false pretensions, he would simply express his deep obligation for the opportunity afforded, and willingly and humbly render every possible aid. Yet he would never set it down to his own credit as a favour conferred upon another, nor would he ever regard the man as his debtor for the service rendered. He is interested only in the good act, but in nothing else springing from it. He expects no reward in return, nor even does he crave enhancement of reputation from it.