Pali text, illustration and English translation of Dhammapada verse 305:

ekāsanaṃ ekaseyyaṃ eko caram atandito |

eko damayam attānaṃ vanante ramito siyā || 305 ||

305. Alone one sits, alone one lies, alone one walks unweariedly, in solitude one tames oneself so in the woods will one delight.

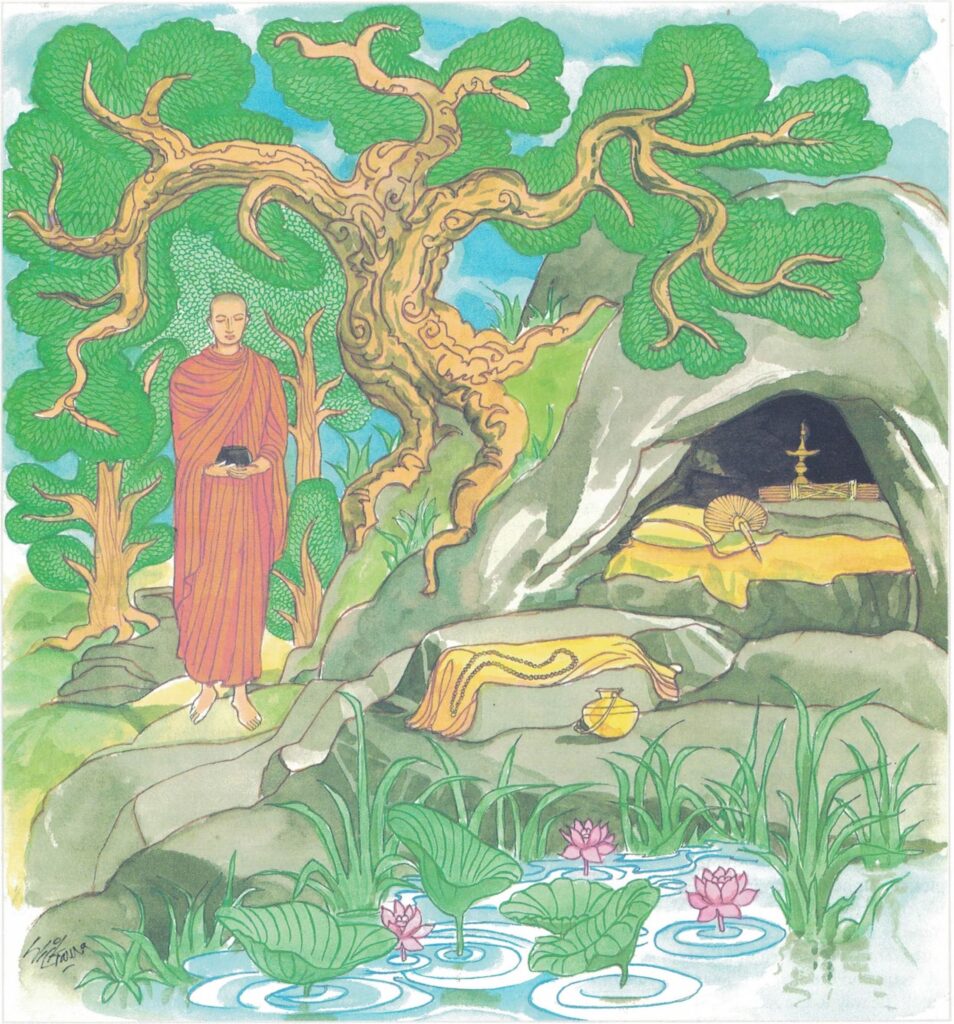

The Story of the Monk Who Stayed Alone

While residing at the Jetavana Monastery, the Buddha spoke this verse with reference to a monk who stayed by himself. Because he usually stayed alone, he was known as Venerable Ekavihāri.

Venerable Ekavihāri did not associate much with other monks, but usually stayed by himself. All alone, he would sleep or lie down, or stand, or walk. Other monks thought ill of Ekavihāri and told the Buddha about him. But the Buddha did not blame him. Instead, he said, “Yes, indeed, my ‘son’ has done well; for, a monk should stay in solitude and seclusion.”

Explanatory Translation (Verse 305)

eko attānaṃ damayaṃ ekāsanaṃ ekaseyyaṃ

atandito eko caram vanante ramito siyā

eko: he, all alone; attānaṃ damayaṃ [damaya]: disciplines himself; ekāsanaṃ [ekāsana]: sits all alone; ekaseyyaṃ [ekaseyya]: sleeps alone; atandito [atandita]: without feeling lethargic; eko: all alone; caram: goes about; vanante: the deep forest; ramito [ramita]: takes delight in

He who sits alone, lies down alone, walks alone, in diligent practice, and alone tames himself alone should find delight in living in the forest.

Commentary and exegetical material (Verse 305)

vanante ramito: takes delight in the forest. This stanza was spoken by the Buddha to extol the virtues of a monk who took delight in forestdwelling. The special qualities of the forest for a monk in meditation are given this way.

According to the explanation given in the vinaya, a forest embraces all that which lies outside a village and its precincts. The Abhidhamma states that the forest commences when one passes the village-outpost. But, in regard to ascetic practices, as we learn from the Suttanta explanation, a forest-dwelling is said to be at least five hundred bow-lengths distant from the village boundary.

The following are the advantages of living in the forest: a monk who lives in a forest can easily acquire concentration not yet acquired, or develop that which has already been attained. Moreover, his teacher is pleased with him, just as the Buddha said: I am pleased with the forest-life of the monk, Nāgita. The mind of him who lives in a forest-dwelling is not distracted by undesirable objects. As he is sustained by the necessary qualification of moral purity he is not overcome, when living in the forest, by the terrors which are experienced by those who are impure in word, deed and thought; this is stated in the Bhayabherava Sutta: Putting away all craving for life, he enjoys the blissful happiness of calm and solitude.

In the words of the visuddhi-magga:

Secluded, detached, delighting in solitude,

The monk by his forest-life endears himself unto the Buddha.

Living alone in the forest he obtains that bliss,

Which even the gods with Indra do not taste.

Wearing but paṃsukūla as his armour to the forest battlefield armed with other ascetic vows,

He, before long, shall conquer Māra and his army.

So the wise should delight in the forest-life.