Pali text, illustration and English translation of Dhammapada verse 244-245:

sujīvaṃ ahirikena kākasūrena dhaṃsinā |

pakkhandinā pagabbhena saṃkiliṭṭhena jīvitaṃ || 244 ||

hirimatā ca dujjīvaṃ niccaṃ sucigavesinā |

alīnen’apagabbhena suddhājīvena passatā || 245 ||

244. Easy the life for a shameless one who bold and forward as a crow, is slanderer and braggart too: this one’s completely stained.

245. But hard the life of a modest one who always seeks for purity, who’s cheerful though no braggart, clean-living and discerning.

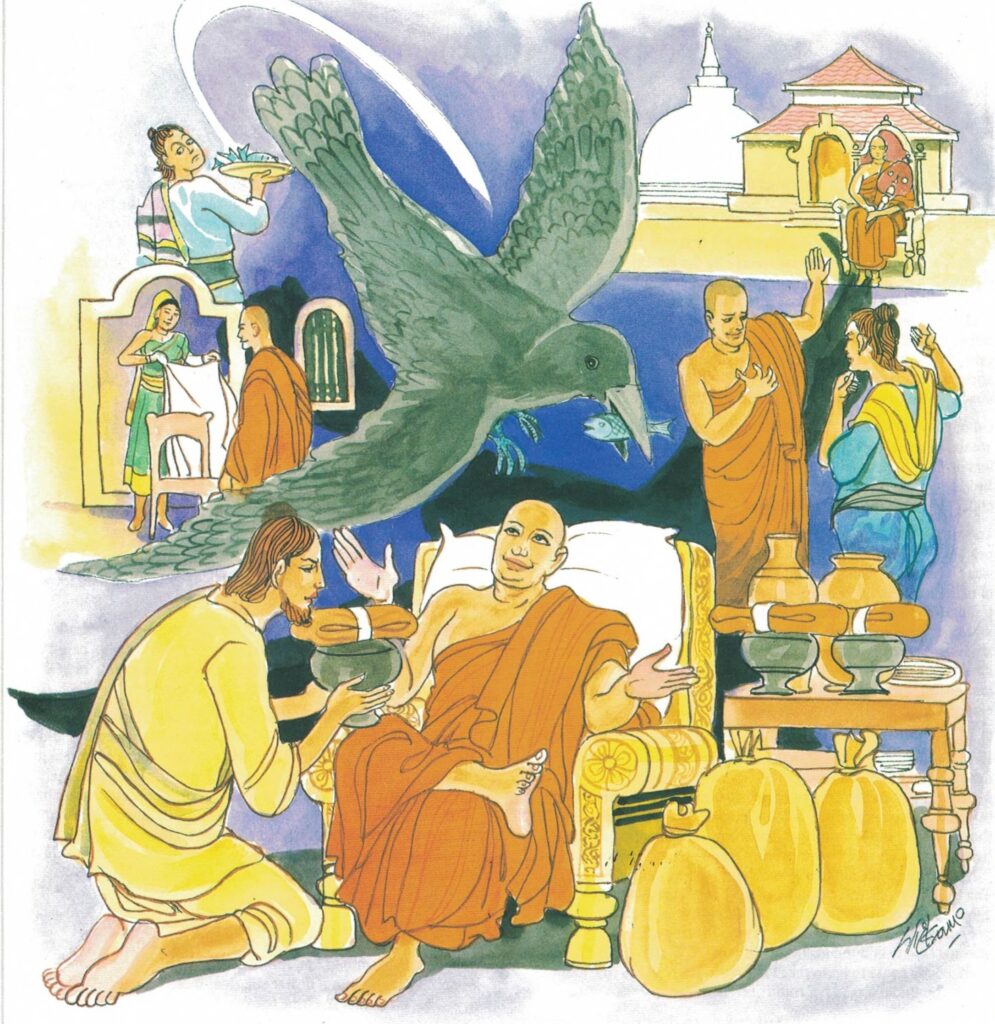

The Story of Culla Sārī

While residing at Jetavana Monastery, the Buddha spoke these Verses, with reference to a monk named Culla Sārī who practiced medicine.

The story goes that one day this monk administered medical treatment, in return for which he received a portion of choice food. As he went out with this food, he met a Venerable on the road and said to him, “Venerable, here is some food which I received for administering medical treatment. Nowhere else will you receive food like this. Take it and eat it. Henceforth, whenever I receive such food as this in return for administering medical treatment, I will bring it to you.” The Venerable listened to what he said, but departed without saying a word. The monks went to the monastery and reported the matter to the Buddha. Said the Buddha, “Monks, he that is shameless and impudent like a crow, he that practises the twenty-one varieties of impropriety, lives happily. But he that is endowed with modesty and fear of mortal sin, lives in sorrow.”

Explanatory Translation (Verse 244)

ahirikena kākasūrena dhaṃsinā pakkhandinā

pagabbhena saṅkiliṭṭhena jīvitaṃ sujīvaṃ

ahirikena: by a shameless person; kākasūrena: sly as a crow; dhaṃsinā: slandering; pakkhandinā: slippery; pagabbhena: slick; saṅkiliṭṭhena: corrupt; jīvitaṃ [jīvita]: living; sujīvaṃ [sujīva]: could be led easily

If an individual possesses no sense of shame, life seems to be easy for him, since he can live whatever way he wants with no thought whatsoever for public opinion. He can do any destruction he wishes to do with the skill of a crow. Just as that of the crow, the shameless person’s life, too, is unclean. He is boastful and goes ahead utterly careless of others.

Explanatory Translation (Verse 245)

hirimatā ca niccaṃ sucigavesinā alīnena

appagabbhena suddhājīvena passatā dujjīvaṃ

hirimatā ca: for a modest person; niccaṃ [nicca]: constantly; sucigavesinā: pursuing what is pure; alīnena: nonattached; appagabbhena: not slick; suddhājīvena: leading a pure life; passatā: possessing insight; dujjīvaṃ [dujjīva]: the life is not easy

The life is hard for a person who is modest, sensitive and inhibited, constantly pursuing what is pure, not attached, who is not slick and impudent, who is leading a pure life and is full of insight.

Commentary and exegetical material (Verse 244-245)

kākasūrena: crafty as a crow. The attitude of the shameless person is compared to that of a crafty crow, lurking until opportunity is ripe for it to snatch whatever it can. The Stanza says that life is easy for such crafty person, but that is not the right attitude for a member of the Sangha (Brotherhood) to adopt. The Brotherhood is the last of the Three Gems of Buddhism.

The last of the Three Refuges, the Jewel of the Sangha is still to be considered. It has been left over for this section as it is more appropriate to consider it under practice. The Teachings of the Buddha are for everyone. No one has ever been excluded from becoming a Buddhist by sex, race or colour. It depends upon the individual Buddhist (and his circumstances) whether he remains a layman or becomes a monk (or nun). The benefit which each class derives from the other is mutual: the laymen give robes, food, shelter and medicines to the monks and these are a monk’s supports for his life. The monks (and nuns) on their part, give something most precious to the laity: the Dhamma as they have studied, practiced and realized it. Thus lay Buddhists can easily find advice and help in a monastery from one of the teachers there or perhaps from a son, uncle or some other relative who is practicing either permanently or for some time as a novice, monk or nun. And so, a balance is preserved, each group giving to the other something necessary for right livelihood.

Monks and novices have sets of rules to guide them in their life and these, being voluntarily observed as ways of self-training, may be equally voluntarily relinquished, as when a monk becomes a novice again or reverts to the state of a layman. In some countries, it is a common practice for laymen to spend some time as a novice or monk, (the latter ordination is only given to persons over the age of twenty years). Usually this is done when a school or college education is over, before taking up work, and for a period of three or four months from approximately July to October or November. This period, when monks must reside in their monastery, is known as the Rains Residence and is meant to be a period devoted to learning, the practice of meditation or some other intensified spiritual activity. After this yearly Rains Residence is over, monks are free to go to other monasteries or into the forest as they wish. In the Buddhist Sangha, monks should not possess money and are to live their lives with few possessions.

As monks, they must, of course, refrain from any sort of sexual intercourse, thus observing ‘chastity’. But they have not the rule to observe unquestioning ‘obedience’ though they have obligations as disciples of a teacher and all good monks honour these strictly. When, after at least five years, they have some learning and experience, knowing their rules well, they are free to wander here and there as they choose, seeking good teachers, or practicing by themselves.

Mention should be made of the four most important precepts in the monk’s code, for breaking which he is expelled from the Sangha, never being able in this life to become a monk again. These four rules are: 1) Never to have any sexual relations; 2) Never deliberately to kill a man, or to order other persons to kill, either other human beings or themselves; 3) Never to take anything that does not belong to one with the intention of possessing it oneself, 4) Never to claim falsely any spiritual attainment, powers, or degree of enlightenment (he is excused if he is mad, conceited or not serious).

A monk’s actual possessions are very few and any other objects around him should be regarded by him as on loan from the Sangha. He has only eight Requisites: an outer double-thick ‘cloak’ an upper-robe, an under-robe, a bowl to collect food, a needle and thread to repair his robes, a waistband for his under-robe, a razor, and a water-strainer to exclude small creatures from his drinking water so that neither they nor himself, are harmed.

As to his duties, they are simple but not easy to perform. He should endeavour to have wide learning and deep understanding of all that his Teacher, the Enlightened One, has taught: he should practice the Teaching, observing Virtue, strengthening Collectedness and developing Wisdom; he will then realize the Buddha’s Teachings according to his practice of them; and finally, depending upon his abilities, he may teach accordingly by his own example, by preaching, by writing books, etc.

When going for Refuge to the Sangha, one should not think of Refugegoing to the whole body of monks for though some of them are Noble, the true nobility experienced after the fire of Supreme Wisdom has burnt up the defilements, a good number are still worldlings practicing Dhamma. Among the laity too, there may be those who are Noble. The Noble monks and laity together form the Noble Sangha which, as it is made up of those who are freeing and have freed themselves from the bondage of all worlds, is truly a secure Refuge. That laypeople may attain this supermundane Nobility should be sufficient to prove that this Teaching is meant also for them, though to do this they must practice thoroughly.

The Jewel of the Sangha has known many great teachers from the immediate disciples of Lord Buddha, such as the Venerables AññāKoṇḍañña, Sāriputta, Moggallāna, Mahākassapa, Ānanda; and Venerable Nuns such as Mahāpajāpati, Khemā, Uppalavannā, Dhammadinnā, with laymen such as the benevolent Anāthapiṇḍika and famous laywomen as was Visākhā and this great procession of Enlightened disciples still continues down the ages to the present day.

Although one may go for Refuge to the exterior Noble Sangha, one should seek for the real Refuge within. This is the collection of Noble Qualities (such as the Powers of Faith, Energy, Mindfulness, Collectedness and Wisdom) which will lead one, balanced and correctly cultured, also to become a member of the Noble Sangha.

After describing Buddhist beliefs and their basis in the Triple Gem or Threefold Refuge, it is now time to outline what Buddhists practice in order to realize the Teachings of the Enlightened One, and so substantiate within their own experience the doctrines which initially they believed.

As a frame for the vast mass of teachings which would qualify to be considered here, an ancient threefold summary of the Teaching is used: virtue, collectedness and wisdom.

Lord Buddha has concisely formulated them in a verse famous in all Buddhist lands:

Never doing any kind of evil, (refers to virtue)

The perfecting of profitable skill, (to collectedness)

Purifying of one’s heart as well, (to wisdom)

This is the Teaching of the Buddhas.

These are known as the three trainings, but since the last one, Wisdom, is both mundane and supermundane, four sections have been devised as comprising the range (though far from the full substance) of the Dhamma: mundane wisdom, virtue, collectedness and supermundane wisdom.

Special Note: There is a strange idea current in some places that Buddhism is only for monks. Nothing could be further from the truth. As we hope to show here, there is something for everyone to do, whether monks or laity. It is true that many of the Buddha’s discourses are addressed to monks but this does not preclude the use of their contents by the laity. How much Buddhist Teaching one applies to one’s life, while to some extent depending on environment: work, family, etc., in the case of lay people, does to a greater extent depend on one’s keenness and determination. The monk is in surroundings more conducive to the application of the Buddha’s Teachings, as he should have less distractions than do the laity. Even among monks, ability and interest naturally vary. The word ‘priest’ should never be used for a bhikkhu, the best translation being ‘monk’.

Buddhist monks and nuns do not beg for their food nor are they beggars. A strict code of conduct regulates a monk’s round to collect food. He may not for instance, make any noise–cry out or sing–in order to attract people’s attention. He walks silently and in the case of meditating monks, with a mind concentrated on his subject of meditation, and accepts whatever people like to give him. Lord Buddha once gravely accepted the offering of a poor child who had nothing else to give except a handful of dust: the child had faith in the Great Teacher. From this, one learns that it is not what is given that is important, but rather, how a thing is given. The monk is to be content with whatever he is given, regarding the food or a medicine to keep the mind-body continuum going on.