Pali text, illustration and English translation of Dhammapada verse 188-192:

bahū ve saraṇaṃ yanti pabbatāni vanāni ca |

ārāmarukkhacetyāni manussā bhayatajjitā || 188 ||

n’etaṃ kho saraṇaṃ khemaṃ n’etaṃ saraṇamuttamaṃ |

n’etaṃ saraṇamāgamma sabbadukkhā pamuccati || 189 ||

yo ca buddhañca dhammañca saṅghañca saraṇaṃ gato |

cattāri ariyasaccāni sammappaññāya passati || 190 ||

dukkhaṃ dukkhasamuppādaṃ dukkhassa ca atikkamaṃ |

ariyaṃ c’aṭṭhaṅgikaṃ maggaṃ dukkhūpasamagāminaṃ || 191 ||

etaṃ kho saraṇaṃ khemaṃ etaṃ saraṇam uttamaṃ |

etaṃ saraṇam āgamma sabbadukkhā pamuccati || 192 ||

188. Many a refuge do they seek on hills, in woods, to sacred trees, to monasteries and shrines they go, folk by fear tormented.

189. Such refuge isn’t secure, such refuge isn’t supreme. From all dukkha one’s not free unto that refuge gone.

190. But going for refuge to Buddha, to Dhamma and the Sangha too, one sees with perfect wisdom the tetrad of the Noble Truths:

191. Dukkha, its causal arising, the overcoming of dukkha, and the Eight-fold Path that’s Noble leading to dukkha’s allaying…

192. …Such refuge is secure, such refuge is supreme. From all dukkha one is free unto that refuge gone.

The Story of a Discontented Young Monk

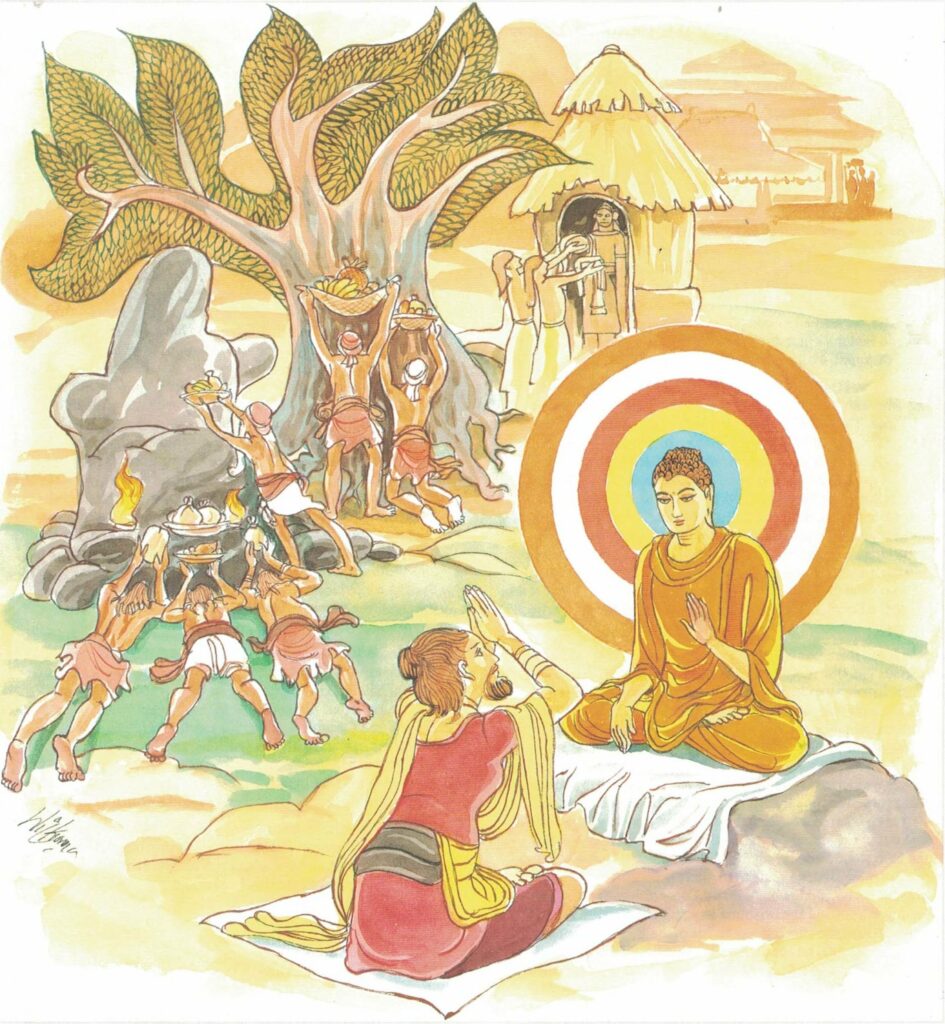

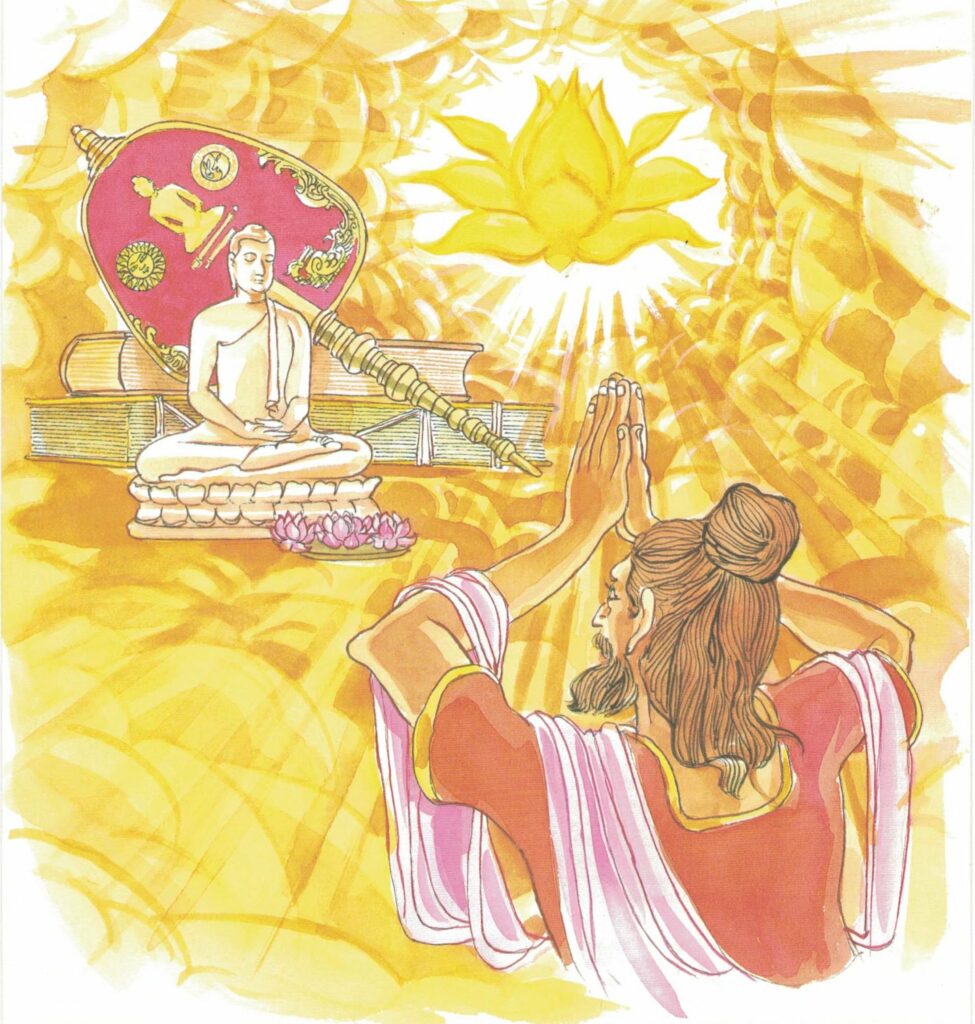

While residing at the Jetavana Monastery, the Buddha spoke these verses, with reference to Aggidatta, a brāhmin.

It appears that Aggidatta was the house-priest of Mahā Kosala. When Mahā Kosala died, his son King Pasenadi Kosala, out of respect for Aggidatta since he had been his father’s housepriest, reappointed him to the same post. Whenever Aggidatta came to wait upon the king, the king would go forth to meet him and would provide him with a seat of equal dignity with himself and say to him, “Teacher, pray sit here.” After a time, however, Aggidatta thought to himself, “This king pays me very great deference, but it is impossible to remain in the good graces of kings for good and all. Life in a king’s household is very pleasant for one who is of equal age with the king. But I am an old man and therefore had best become a monk.” Accordingly Aggidatta asked permission of the king to become a monk, caused a drum to be beaten throughout the city, spent all of his wealth by way of alms in the course of a week, and retired from the world, becoming a monk of an heretical order. A great number of men followed to become monks.

Aggidatta with his monks took up his residence on the frontier of the country of the Angas and Magadhas and the country of the Kurūs. Having so done, he addressed his monks as follows, “Friends, in case any one of you should be troubled with unlawful thoughts, whether lustful, malevolent, or cruel, let each one of you so troubled fill a jar with sand from the river and empty the same in this place.” “Very well,” said the monks, promising to do so. So, whenever they were troubled by unlawful thoughts, whether lustful, malevolent, or cruel, they did as he had commanded them to do. In the course of time there arose a great heap of sand, and Ahicchatta, king of the nāgas (dragons), took possession of it. The dwellers in Anga and Magadha and the dwellers in the kingdom of the Kurus, month by month, brought rich offerings in honour of those monks. Now Aggidatta admonished them as follows, “So surely as you seek refuge in a mountain, so surely as you seek refuge in a forest, so surely as you seek refuge in a grove, so surely as you seek refuge in a tree, even so surely will you obtain release from all suffering.” With this admonition did Aggidatta admonish his disciples.

At this time the future Buddha, after going forth on the great retirement, and after attaining complete enlightenment, took up his residence at Jetavana Monastery near Sāvatthi. Surveying the world at dawn he perceived that the brāhmin Aggidatta, together with his disciples, had entered the net of his knowledge. So he considered within himself, “Do all these living beings possess the faculties requisite for arahatship?” Perceiving that they possessed the requisite faculties, he said in the evening to Venerable Moggallāna, “Moggallāna, do you observe that the brāhmin Aggidatta is urging upon the multitude a course of action other than the right one? Go and admonish them.” “Venerable, these monks are very numerous, and if I go alone, I fear that they will prove to be intractable; but if you also go, they will be tractable.” “Moggallāna, I will also go, but you go ahead.”

As the Venerable proceeded, he thought to himself, “These monks are both powerful and numerous. If I say a word to them when they are all gathered together, they will all rise against me in troops.” Therefore by his own supernatural power he caused great drops of rain to fall. When those great drops of rain fell, the monks arose, one after another, and each entered his own bower of leaves and grass. The Venerable went and stood at the door of Aggidatta’s leafy hut and called out, “Aggidatta!” When Agidatta heard the sound of the Venerable’s voice, he thought to himself, “There is no one in this world who is able to address me by name; who can it be that thus addresses me by name?” And in the stubbornness of pride, he replied, “Who is that?” “It is I, brāhmin.” “What have you to say?” “Show me a place here where I can spend this one night.” “There is no place for you to stay here; here is but a single hut of leaves and grass for a single monk.” “Aggidatta, men go to the abode of men, cattle to the abode of cattle, and monks to the abode of monks; do not so; give me a lodging.” “Are you a monk?” “Yes, I am a monk.” “If you are a monk, where is your alms vessel? What monastic utensils have you?” “I have utensils, but since it is inconvenient to carry them about from place to place, I procure them within and then go my way.” “So you intend to procure them within and then go your way!” said Aggidatta angrily to the Venerable. The Venerable said to him, “Go away, Aggidatta, do not be angry; show me a place where I can spend the night.” “There is no lodging here.” “Well, who is it that lives on that pile of sand?” “A certain nāga-king.” “Give the pile of sand to me.” “I cannot give you the pile of sand; that would be a grievous affront to him.” “Never mind, give it to me.” “Very well; you alone seem to know.”

The Venerable started towards the pile of sand. When the nāga-king saw him approaching, he thought to himself. “Yonder monk approaches hither. Doubtless he does not know that I am here. I will spit fire at him and kill him.” The Venerable thought to himself, “This nāga-king doubtless thinks, ‘I alone am able to spit smoke; others are not able to do this.’” So the Venerable spat fire himself. Puffs of smoke arose from the bodies of both and ascended to the World of Brahma. The puffs of smoke gave the Venerable no trouble at all, but troubled the nāga-king sorely. The nāga-king, unable to stand the blasts of smoke, burst into flames. The Venerable applied himself to meditation on the element of fire and entered into a state of trance. Thereupon he burst into flames which ascended to the World of Brahma. His whole body looked as if it had been set on fire with torches. The company of sages looked on and thought to themselves, “The nāga-king is burning the monk; the good monk has indeed lost his life by not listening to our words.” When the Venerable had over-mastered the nāga-king and made him quit his misdoing, he seated himself on the pile of sand. Thereupon the nāga-king surrounded the pile of sand with good things to eat, and creating a hood as large as the interior of a peak-house, held it over the Venerable’s head.

Early in the morning the company of sages thought to themselves, “We will find out whether the monk is dead or not.” So they went to where the Venerable was, and when they saw him sitting on the pile of sand, they did reverence to him and praised him and said, “Monk, you must have been greatly plagued by the nāga-king.” “Do you not see him standing there with his hood raised over my head?” Then said the sages, “What a wonderful thing the monk did in conquering so powerful a nāgaking!” And they stood in a circle about the Venerable.

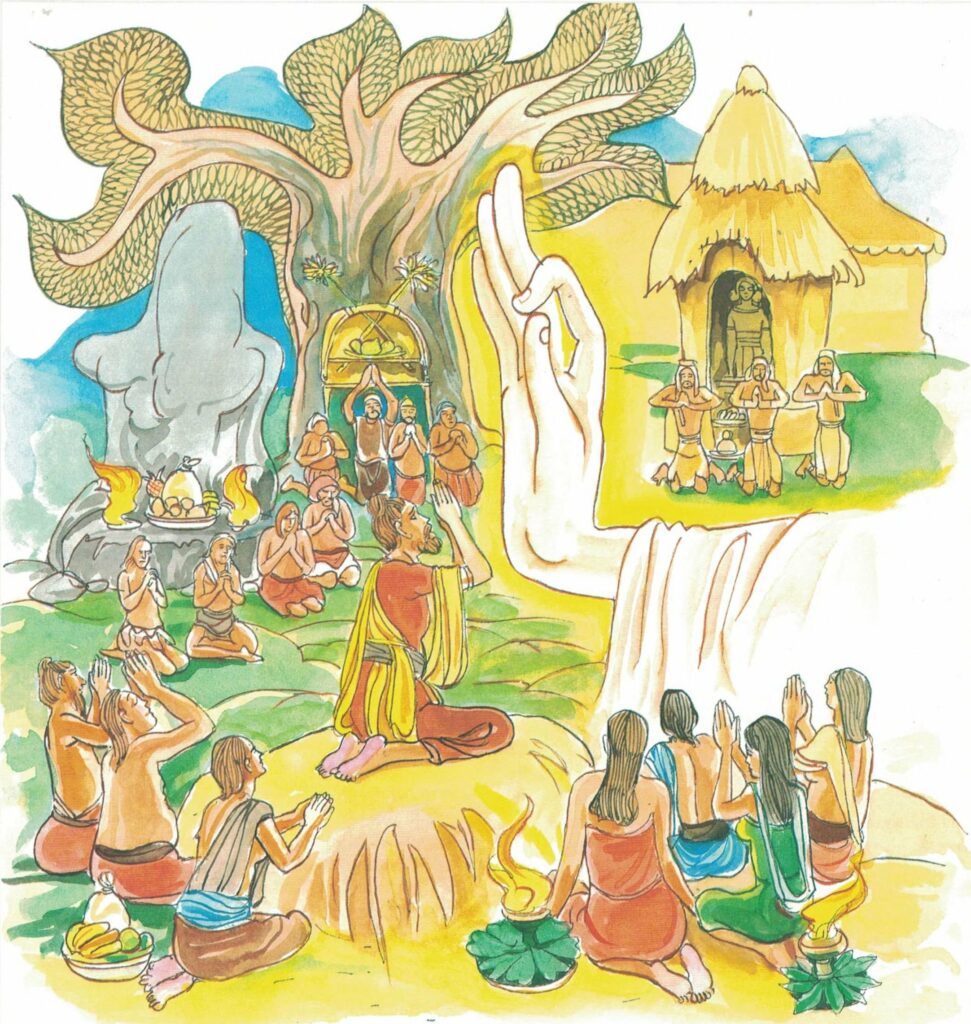

At that moment, the Buddha drew near. The Venerable, seeing the Buddha, arose and saluted him. Said the sages to the Venerable, “Is this man greater than you?” The Venerable replied, “This is the Buddha; I am only his disciple.” The Buddha seated himself on the summit of the pile of sand. The company of sages said to each other, “If such is the supernatural power of a mere disciple, what must the supernatural power of this man like?” And, extending their clasped hands in an attitude of reverent salutation, they bestowed praise on the Buddha. The Buddha said to Aggidatta, “Aggidatta, in giving admonition to your disciples and supporters, how do you admonish them?” Aggidatta replied, “I admonish them thus, ‘Seek refuge in this mountain, seek refuge in this forest, or grove, or tree. For he who seeks refuge in these obtains release from all suffering.’” The Buddha said, “No indeed, Aggidatta, he who seeks refuge in these does not obtain release from suffering. But he who seeks refuge in the Buddha, the Dhamma, and the Sangha, he obtains release from the round of suffering.”

At the conclusion of the lesson all those sages attained arahatship, together with the superhuman faculties. Thereupon they saluted the Buddha and asked to be admitted to the Sangha. The Buddha stretched out his hand from under his robe and said, “Come, monks! Lead the religious life.” That very instant they were furnished with the eight requisites and became as it were monks of a hundred years.

Now this was the day when all the dwellers in Anga and in Magadha and in the country of the Kurus were accustomed to come with rich offerings. When, therefore, they approached with their offerings, and saw that all those sages had become monks, they thought to themselves, “Is our brāhmin Aggidatta great, or is the monk Gotama great?” And because the Buddha had but just arrived, they concluded, “Aggidatta alone is great.” The Buddha surveyed their thoughts and said, “Aggidatta, destroy the doubt that exists in the minds of your disciples.” Aggidatta replied, “That is the very thing I desire to do.” So by superhuman power he rose seven times in the air, and descending to the ground, he saluted the Buddha and said, “Venerable, you are my Teacher and I am your disciple.” Thus did Aggidatta speak, declaring himself the disciple of the Buddha.

Explanatory Translation (Verse 188)

bhayatajjitā manussā pabbatāni vanāni ārāma

rukkha cetyāni ca ve bahuṃ saraṇaṃ yanti

bhayatajjitā: trembling in fear; manussā: human beings; pabbatāni: rocks; vanāni: forests; ārāma: parks; rukkha: trees; cetyāni ca: and shrines; ve: decidedly; bahuṃ saraṇaṃ [saraṇa]: many refuges; yanti: go to

Human beings who tremble in fear seek refuge in mountains, forests, parks, trees, and shrines.

Explanatory Translation (Verse 189)

etaṃ saraṇaṃ kho na khemaṃ etaṃ saraṇaṃ na uttamaṃ

etaṃ saraṇaṃ āgamma, sabbadukkhā na pamuccati

etaṃ saraṇaṃ kho: this kind of refuge certainly; na khemaṃ [khema]: is not secure; etaṃ saraṇaṃ [saraṇa]: this kind of refuge; na uttamaṃ [uttama]: is not supreme; etaṃ saraṇaṃ āgamma: coming to that refuge; sabbadukkhā: from all sufferings; na pamuccati: one is not released

These are not secure refuges. They are not the supreme refuge. One who takes refuge in them is not released from all sufferings.

Explanatory Translation (Verse 190)

yo ca Buddhañca Dhammañca Sanghañca saraṇaṃ

gato cattāri ariyasaccāni sammappaññāya passati

yo ca: if someone; Buddhañca: in the Buddha; Dhammañca: in the Dhamma; Sanghañca: and in the Sangha (Order); saraṇaṃ gato;takes refuge; cattāri ariyasaccāni: four extraordinary realities;sammā: well; paññāya: with penetrative insight; passati: (he) will see

If a wise person were to take shelter in the Buddha, the Dhamma and the Sangha, he will observe the four Noble Truths with high wisdom.

Explanatory Translation (Verse 191)

dukkhaṃ dukkhasamuppādaṃ dukkhassa atikkamaṃ ca

dukkhūpasamagāminaṃ ariyaṃ aṭṭhaṅgikaṃ maggaṃ ca

dukkhaṃ [dukkha]: suffering; dukkhasamuppādaṃ [dukkhasamuppāda]: arisen of suffering; dukkhassa atikkamaṃ [atikkama]: ending suffering; ca dukkhūpasamagāminaṃ [dukkhūpasamagāmina]: and the way to the end of suffering; ariyaṃ aṭṭhaṅgikaṃ maggaṃ [magga]: (that is) the eight-fold path

The four extraordinary realities are: suffering; the arising of suffering; the ending of suffering; the eightfold path leading to the ending of suffering.

Explanatory Translation (Verse 192)

etaṃ saraṇaṃ kho khemaṃ etaṃ saraṇaṃ uttamaṃ

etaṃ saraṇaṃ āgamma, sabbadukkhā pamuccati

etaṃ saraṇaṃ kho: indeed this refuge is; khemaṃ [khema]: secure; etaṃ saraṇaṃ [saraṇa]: this refuge; uttamaṃ [uttama]: is supreme; etaṃ saraṇaṃ āgamma: when you arrive in this refuge; sabbadukkhā: of all suffering; pamuccati: (you are) set free

This refuge in the Triple Refuge is, of course, totally secure. This is the supreme refuge. Once you take this refuge you gain release from all your sufferings.

Commentary and exegetical material (Verse 188-192)

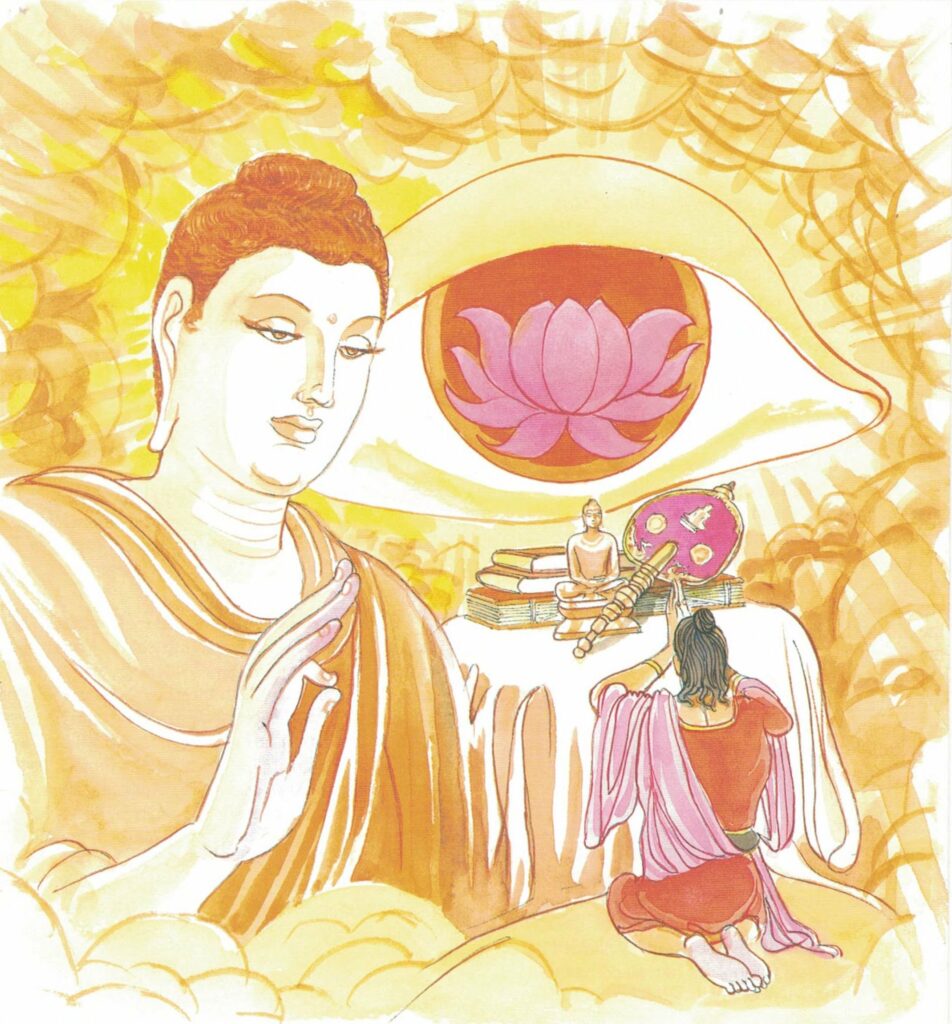

N’etaṃ kho saraṇaṃ khemaṃ: One’s best refuge is oneself. A Buddhist seeks refuge in the Buddha, the Dhamma and the Saṅgha as the Teacher, the Teaching and the Taught in order to gain his deliverance from the ills of life. The Buddha is the supreme teacher who shows the way to deliverance. The Dhamma is the unique way. The Saṅgha represents the Taught who have followed the way and have become living examples. One formally becomes a Buddhist by intelligently seeking refuge in this Triple Gem (Tisaraṇa). A Buddhist does not seek refuge in the Buddha with the hope that he will be saved by a personal act of deliverance. The confidence of a Buddhist in the Buddha is like that of a sick person in a noted physician, or of a student in his teacher.

yo ca Budhanca Dhammañca Sanghañca saraṇaṃ gato: Those who take refuge in the Buddha, the Dhamma and the Sangha. Though the Sangha began its career with only sixty disciples, it expanded into thousands, and in those early days an adherent sought entry into it by pronouncing the three-fold formula known as the Three Refuges:

Buddhaṃ saraṇaṃ gacchāmi

Dhammaṃ saraṇaṃ gacchāmi

Sanghaṃ saraṇaṃ gacchāmi

Dutiyampi Buddhaṃ Saraṇaṃ Gacchāmi

Dutiyampi Dhammaṃ saraṇaṃ gacchāmi

Dutiyampi Sanghaṃ saraṇaṃ gacchāmi

Tatiyampi Buddhaṃ saraṇaṃ gacchāmi

Tatiyampi Dhammaṃ saraṇaṃ gacchāmi

Tatiyampi Sanghaṃ saraṇaṃ gacchāmiI go for refuge to the Buddha (the Teacher)

I go for refuge to the Dhamma (the Teaching)

I go for refuge to the Sangha (the Taught)

For the second time I go for refuge to the Buddha

For the second time I go for refuge to the Dhamma

For the second time I go for refuge to the Sangha

For the third time I go for refuge to the Buddha

For the third time I go for refuge to the Dhamma

For the third time I go for refuge to the Sangha

Here the Buddha lays special emphasis on the importance of individual striving for purification and deliverance from the daily ills of life. There is no efficacy in praying to others or in depending on others. One might question why Buddhists should seek refuge in the Buddha, Dhamma, and the Sangha, when the Buddha had explicitly advised His followers not to seek refuge in others. In seeking refuge in the Triple Gem, Buddhists only regard the Buddha as an instructor who merely shows the path of Deliverance, the Dhamma as the only way or means, the Sangha as the living examples of the way of life to be lived. Buddhists do not consider that they would gain their deliverance by merely reciting these words of commitment. One has to begin the practice of it.

cattāri ariyasaccāni: the four extraordinary realities. Sacca is the Pāli term for reality, which means the reality that the Buddha awakened to, which is different from the ordinary and, therefore, is extraordinary. The Buddha enunciates a four-fold reality which provides foundation for His teaching, which is associated with the so-called existence or being. Whether the Buddhas arise or not, this reality remains and it is a Buddha who reveals it to the deluded world. It does not and cannot change with time, because it is available always. The Buddha was not indebted to anyone for his realization of it, as He Himself remarked in his discourse thus: “With regard to things unheard of before, there arose in me the eye, the knowledge, the gnosis, the insight and the light.” These words are very significant because they testify to the originality of His experience.

This reality, in Pāli, is termed ariya saccāni. They are so called because they were discovered by the Greatest Ariya, that is, one who has transcended the ordinary state and becomes extraordinary. The term ariya, usually translated noble, is here translated extraordinary, as opposed to the ordinary (puthujjana). We are making a distinction between ordinary or naive reality as seen by the common man on the street and the extraordinary reality experienced by the Buddha and his disciples.

The first part of the extraordinary reality deals with dukkha which, for need of a better English equivalent, is rendered suffering. As a feeling dukkha means pain. What is painful is, in short, the personality which is an impossible burden that we constantly carry. We are unable to maintain it because it is unrealistic. Unhappiness results from the attempt to do the impossible.

Average men are only surface-seers. An ariya sees things as they truly are. To an ariya life is suffering and he finds no real happiness in this world which deceives with illusory pleasures. Material happiness is merely the gratification of some desire.

All are subject to birth (jāti) and, consequently, to decay (jarā), disease (vyādhi) and finally to death (maraṇa). No one is exempt from these four phases of life. Life is not a static entity. It is a dynamic process of change. Self is a static concept that we try to maintain in a dynamic reality. This wish, when unfulfilled, is suffering. While trying to maintain this self one meets unfavourables or one is separated from things or persons. At times, what one least expects or what one least desires, is thrust on oneself. Such unexpected, unpleasant circumstances become so intolerable and painful that weak people sometimes commit suicide as if such an act would solve the problem.

The cause of this suffering is an emotional urge to ‘personalise’ what is experienced. The personality comes into being through this personalization.

There are three kinds of urges.

- The first is the urge to enjoy sensual pleasures (kāmataṇhā).

- The second is the urge to exist or be (bhavataṇhā).

- The third is the urge to stop existing (vibhavataṇhā).

According to the commentaries, the last two urges are connected with the belief in eternalism (sassatadiṭṭhi) and the belief in annihilationism (ucchedadiṭṭhi). Bhavataṇhā may also be interpreted as attachment to realms of form and vibhavataṇhā, as attachment to formless realms since rūparāga and arūparāga are treated as two fetters (samyojanas).

This urge is a powerful emotional force latent in all, and is the chief cause of the ills of life. It is this urge which, in gross or subtle form, leads to repeated births in saṃsāra and which makes one hold on to all forms of life and personality.

The grossest forms of this urge for pleasure are attenuated on attaining sakadāgāmi, the second stage of sainthood, and it is completely eradicated on attaining anāgāmi, the third stage of sainthood. The subtle forms of the urge for existence and non-existence are eradicated on attaining arahatship.

The third aspect of the extraordinary reality is the complete cessation of suffering which is Nibbāna, the ultimate goal of Buddhists. It can be achieved in this life itself by the total eradication of all urges. This Nibbāna is to be realized (sacchikātabba) by renouncing all attachment to the external world. This is the depersonalization of the aggregate of personalized phenomena (pancupādānakkhanda) which comprise the personality or self.

This third extraordinary reality has to be realized by developing (bhāvetabba) the extraordinary eight-fold path (ariyaṭṭhaṅgika magga). This unique path is the only straight way to Nibbāna. This is the fourth extraordinary reality.

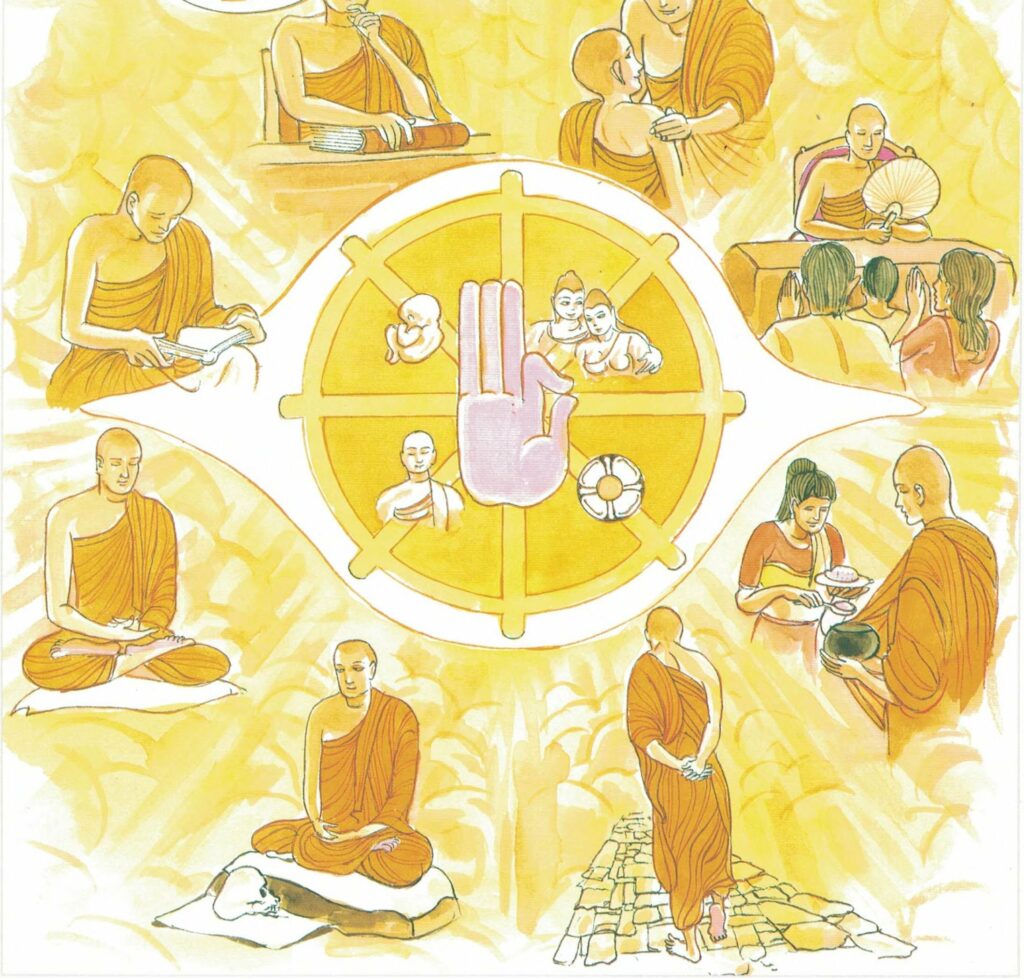

ariyañchaṭṭhangikaṃ maggaṃ: the extraordinary eight-fold path. This unique way avoids the two extremes: self-mortification that weakens one’s body and self-indulgence that retards one’s mind.

It consists of the following eight factors:

- Harmonious perspective (Sammā Diṭṭhi);

- Harmonious feeling (Sammā Saṃkappa);

- Harmonious speech (Sammā Vācā);

- Harmonious action (Sammā Kammanta);

- Harmonious living (Sammā Ajīva);

- Harmonious practice (Sammā Vāyāma);

- Harmonious introspection (Sammā Sati);

- Harmonious equilibrium (Sammā Samādhi).

1. Harmonious perspective is explained as the knowledge of the four extraordinary realities. In other words, it is the understanding of oneself as one really is, because, as the Rohitassa Sutta states, these truths are concerned with the one-fathom long body of man. The keynote of Buddhism is this harmonious perspective which removes all conflicts within and without.

2. Clear vision leads to clear feeling. The second factor of the path is, therefore, Sammā Saṃkappa. The English renderings–right resolutions, right aspirations–do not convey the actual meaning of the Pāli term. Right feelings may be suggested as the nearest English equivalent.

It is the emotional state or feelings that either defiles or purifies a person. Feelings mould a person’s nature and control destiny. Evil feelings tend to debase one just as good feelings tend to elevate a person. Sometimes a single feeling can either destroy or save.

Sammā Saṃkappa serves the double purpose of eliminating bad feelings and thoughts and developing good feelings. Right feelings, in this particular context, are three-fold. They consist of. (i) Nekkhamma–desire for renunciation of worldly pleasures, which is opposed to attachment, selfishness, and self-possessiveness; (ii) Avyāpāda–feelings of loving-kindness, goodwill, or benevolence, which are opposed to hatred, ill-will, or aversion, and (iii) Avihiṃsā–feelings of harmlessness or compassion, which are opposed to cruelty and callousness.

These evil and good feelings are latent in all. As long as we are ordinary people, bad feelings rise to the surface at unexpected moments in great strength. When they are totally eradicated on attaining arahatship, one’s stream of consciousness becomes pure.

Harmonious feelings automatically lead to harmonious speech and action, which results in a harmonious life.

These good feelings, however, have to be maintained only by constant practice in preventing and eliminating evil thoughts and the cultivation and maintenance of good thoughts. This leads to constant introspective awareness of the experience within. This results in the attainment of mental equilibrium. This undisturbed mind is aware of reality. This awareness maintains the peace that cannot be disturbed.