Pali text, illustration and English translation of Dhammapada verse 186-187:

na kahāpaṇavassena titti kāmesu vijjati |

appassādā dukhā kāmā iti viññāya paṇḍito || 186 ||

api dibbesu kāmesu ratiṃ so nādhigacchati |

taṇhakkhayarato hoti sammāsambuddhasāvako || 187 ||

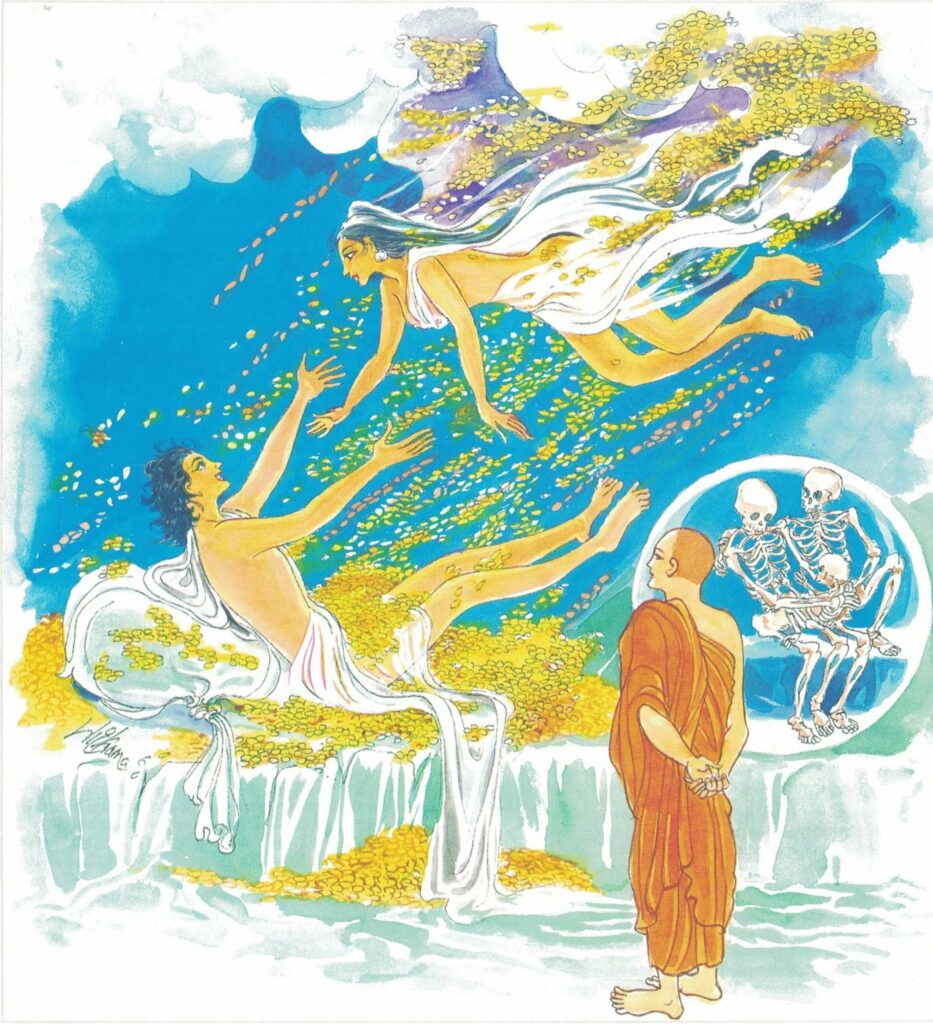

186. Not by a rain of golden coins is found desires’ satiety, desires are dukkha, of little joy, thus a wise one understands.

187. Even with pleasures heavenly that one finds no delight, the perfect Buddha’s pupil delights in craving’s end.

The Story of a Discontented Young Monk

While residing at the Jetavana Monastery, the Buddha spoke these verses, with reference to a young monk who was discontented as a monk.

The story goes that after this monk had been admitted to the Sangha and had made his full profession, his preceptor sent him forth, saying, “Go to such and such a place and learn the Ordinances.” No sooner had the monk gone there than his father fell sick. Now the father desired greatly to see his son, but found no one able to summon him. When he was at the point of death, he began to chatter and prattle for love of his son. Putting a hundred pieces of money in the hands of his youngest son, he said to him, “Take this money and use it to buy a bowl and robe for my son.” In so saying, he died.

When the young monk returned home, his youngest brother flung himself at his feet, and rolling on the ground, wept and said, “Venerable, your father was praising you when he died and placed in my hand a hundred pieces of gold. What shall I do with it?” The young monk refused to take the money, saying, “I have no need of this money.” After a time, however, he thought to himself, “What is the use of living if I am obliged to gain my living by going from house to house for alms? These hundred pieces are enough to keep me alive; I will return to the life of a layman.”

Oppressed with discontent, he abandoned the recitation of the Sacred Texts and the Practice of Meditation, and began to look as though he had jaundice. The youths asked him, “What is the matter?” He replied, “I am discontented.” So they reported the matter to his preceptor and to his teacher, and the latter conducted him to the Buddha and explained what was the matter with him.

The Buddha asked him, “Is the report true that you are discontented?” “Yes, Venerable,” he replied. Again the Buddha asked him, “Why have you acted thus? Have you any means of livelihood?” “Yes, venerable.” “How great is your wealth?” “A hundred gold pieces, venerable.” “Very well; just fetch a few potsherds hither; we will count them and find out whether or not you have sufficient means of livelihood.” The discontented monk brought the potsherds. Then the Buddha said to him, “Now then, set aside fifty for food and drink, twenty-four for two bullocks, and an equal number for seed, for a two-bullockplow, for a spade, and for a razor adze.” The result of the count proved that the hundred gold pieces would be insufficient.

Then said the Buddha to him, “Monk, the pieces of money which you possess are but few in number. How can you hope to satisfy your desire with so few as these? In times past lived men who exercised sway as universal monarchs, men who by a mere waving of the arms were able to cause a rain of jewels to fall, covering the ground for twelve leagues waist-deep with jewels; these men ruled as kings until thirty-six sakkas had died; and, although exercising sovereignty over the deities for so long, died, without having fulfilled their desires.”

Explanatory Translation (Verse 186)

kahāpaṇa vassena kāmesu titti na vijjati

paṇḍito kāmā appassādā dukhā iti viññāya

kahāpaṇa vassena: even by a shower of golden coins; kāmesu: desire of sensualities; titti: satiation; na vijjati: is not seen; paṇḍito [paṇḍita]: a wise person; kāmā: sensual pleasures; appassādā: (considers) as unsatisfied; dukhā: (and) painful); iti: this way; viññāya: having understood

Insatiable are sensual desires. Sensual desire will not be satisfied even with a shower of gold. The wise know that sensual pleasures bring but little satisfaction and much pain.

Explanatory Translation (Verse 187)

so dibbesu kāmesu api ratim nādhigacchati

sammāsambuddhasāvako taṇhakkhayarato hoti

so: he; dibbesu: (even in) heavenly; kāmesu api: pleasures; ratim: indulgence; nādhigacchati: will not approach; sammāsambuddhasāvako [sammāsambuddhasāvaka]: that disciple of the Enlightened One; taṇhakkhayarato [taṇhakkhayarata]: mind fixed only on ending of desire; hoti: is he

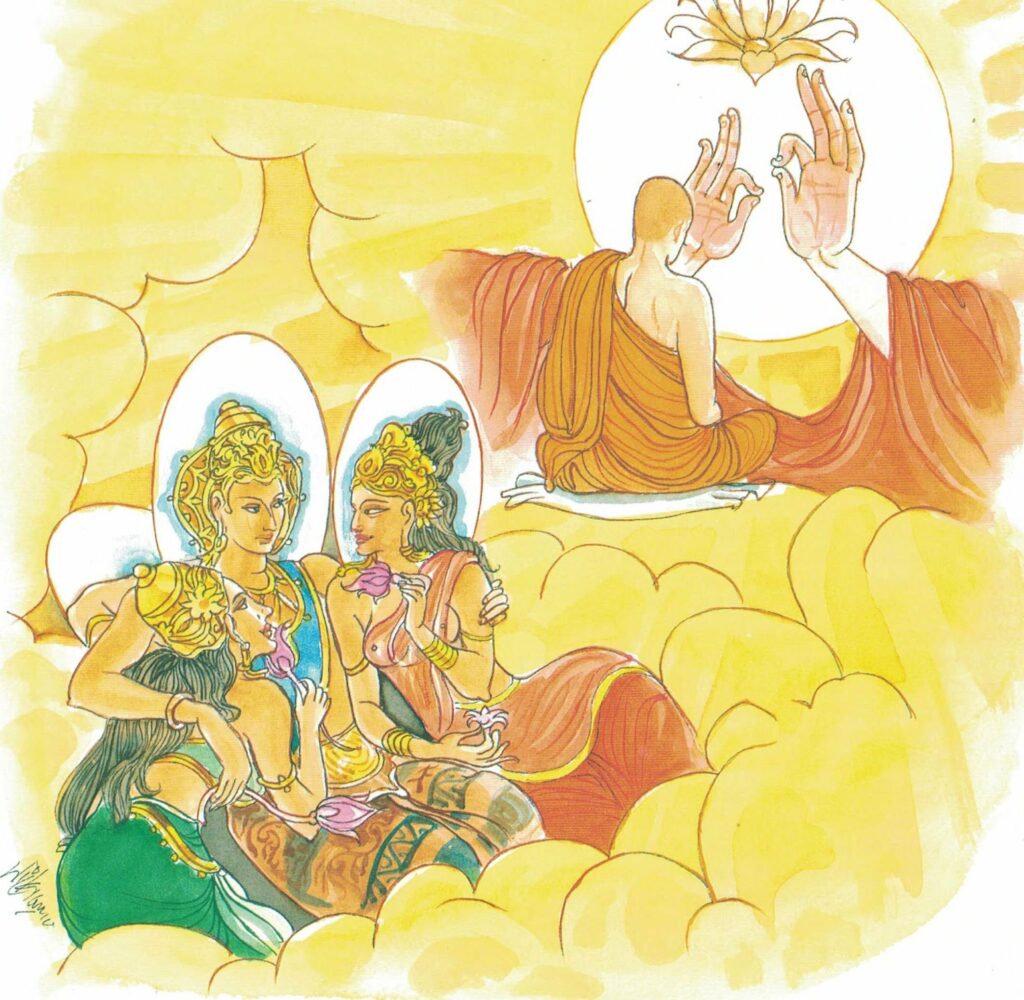

The disciple of the Buddha does not even go after heavenly pleasures. The disciple of the Buddha has his mind fixed only on the process of ending cravings.

Commentary and exegetical material (Verse 186-187)

sammā sambuddha sāvakā: the disciples of the Buddha. The long line of monk disciples of the Buddha started with the promulgation of the First Sermon of the Buddha–Dhammacakka Pavattana Sutta. This was addressed to the five ascetics. Eventually all the five of them attained arahatship–the highest stage of spiritual attainment. The five learned monks who thus attained arahatship and became the Buddha’s first disciples were the brāhmins Koṇḍañña, Bhaddiya, Vappa, Mahānāma, and Assaji.

Koṇḍañña was the youngest and the cleverest of the eight brāhmins who were summoned by King Suddhodana to name the infant prince. The other four were the sons of those older brāhmins. All these five retired to the forest as ascetics in anticipation of the Bodhisatta while he was endeavouring to attain Buddhahood. When he gave up his useless penances and severe austerities and began to nourish the body sparingly to regain his lost strength, these favourite followers, disappointed at his change of method, deserted him and went to Isipatana. Soon after their departure the Bodhisatta attained Buddhahood. The venerable Koṇḍañña became the first arahat and the most senior member of the Sangha. It was Assaji, one of the five, who converted the great Sāriputta, the chief disciple of the Buddha. From then on the number of the brotherhood increased.

In Vārānasi, there was a millionaire’s son, named Yasa, who led a luxurious life. One morning he rose early and, to his utter disgust, saw his female attendants and musicians asleep in a repulsive posture. The sight was so disgusting that the palace presented the gloomy appearance of a charnel house. Realizing the vanities of worldly life, he stole away from home, saying, “Distressed am I, oppressed am I”, and went in the direction of Isipatana where the Buddha was temporarily residing after the five monks attained arahatship. At that particular time the Buddha, as usual, was pacing up and down in an open space. Seeing him coming from afar, the Buddha came out of His ambulatory and sat on a prepared seat. Not far from Him stood Yasa, crying, “O’ distressed am I! Oppressed am I!” Thereupon the Buddha said, “Here there is no distress, O’ Yasa! Here there is no oppression. O’ Yasa! Come hither, Yasa! Take a seat. I shall expound the Dhamma to you.” The distressed Yasa was pleased to hear the encouraging words of the Buddha. Removing his golden sandals, he approached the Buddha, respectfully saluted Him and sat on one side. The Buddha expounded the doctrine to him, and he attained the first stage of sainthood (sotāpatti). At first the Buddha spoke to him on generosity (dāna), morality (sīla), celestial states (sagga), the evils of sensual pleasures (kāmādīnava), the blessings of renunciation (nekkhammānisaṃsa). When He found that his mind was pliable and was ready to appreciate the deeper teaching He taught the Four Noble Truths.

Yasa’s mother was the first to notice the absence of her son and she reported this to her husband. The man immediately dispatched horsemen in four directions and he himself went towards Isipatana, following the imprint of the golden slippers. The Buddha saw him coming from afar and, by His psychic powers, willed that he should not be able to see his son. When he approached the Buddha and respectfully inquired whether He had seen his son Yasa, the Buddha answered, “Well, then, sit down here please. You will be able to see your son”. Pleased with the happy news, he sat down. The Buddha delivered a discourse to him, and he was so delighted that he exclaimed, “Excellent, O’ Lord, excellent! It is as if a man were to set upright that which was overturned, or were to hold a lamp amidst the darkness, so that those who have eyes may see!” Even so has the doctrine been expounded in various ways by the Buddha. “I take refuge in the Buddha, the Doctrine and the Sangha. May Buddha receive me as a follower, who has taken refuge from this very day to life’s end!” He was the first lay follower to seek refuge with the three-fold formula. On hearing the discourse delivered to his father, Yasa attained arahatship. Thereupon the Buddha withdrew His will-power so that Yasa’s father would be able to see his son. He beheld his son and invited the Buddha and His disciples for alms on the following day. The Buddha expressed His acceptance of the invitation by His silence. After the departure of the millionaire Yasa begged the Buddha to grant him the Lesser and the Higher Ordination. “Come, O’ Monks! Well taught is the Doctrine. Lead the religious life to make a complete end of suffering.” With these words the Buddha conferred on him the Higher Ordination. With the Venerable Yasa, the number of arahats increased to six.

As invited, the Buddha visited the millionaire’s house with His six disciples. Venerable Yasa’s mother and his former wife heard the doctrine expounded by the Buddha and, having attained the first stage of Sainthood, became His first two lay female followers. Venerable Yasa had four distinguished friends named Vimala, Subhāhu, Puṇṇaji and Gavampati. When they heard that their noble friend shaved his hair and with a yellow robe, entered the homeless life, they approached Venerable Yasa and expressed their desire to follow. Venerable Yasa introduced them to the Buddha, and, on hearing the Dhamma, they also attained arahatship.

Fifty more worthy friends of Venerable Yasa, who belonged to leading families of various districts, also receiving instructions from the Buddha, attained arahatship and entered the Sangha. Hardly two months had elapsed since His Enlightenment when the number of arahats gradually rose to sixty. All of them came from distinguished families and were worthy sons of worthy fathers. The Buddha, who long before succeeded in enlightening sixty disciples, decided to send them as messengers of Truth to teach His new Dhamma to all without any distinction. Before dispatching them in various directions He exhorted them as follows:

“Freed am I, O’ Monks, from all bonds, whether divine or human.

“You, too, O’ Monks, are freed from all bonds, whether divine or human.

“Go forth, O’ Monks, for the good of the many, for the happiness of the many, out of compassion for the world, for the good, benefit, and happiness of gods and men. Let not two go by one way:

Preach, O’ Monks, the Dhamma, excellent in the beginning, excellent in the middle, excellent in the end, both in the spirit and in the letter. Proclaim the holy life, altogether perfect and pure.”