An idea that perhaps took shape in conversations that Jamsetji Tata and Swami Vivekananda had on a voyage in 1893 would not come to fruition before their deaths.

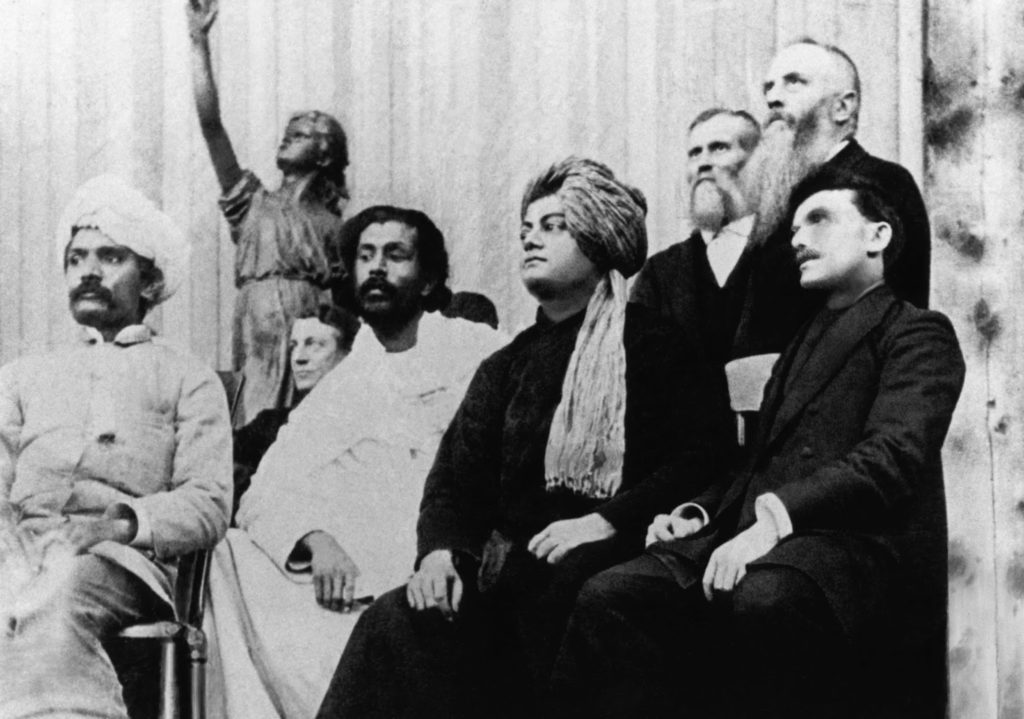

It was in the summer of 1893 that two Indians, very different in their vocations, happened to travel together on a ship from Yokohama in Japan to Vancouver in Canada. One of them was a young 30-year-old unknown monk and the other a very successful trader-industrialist. In their conversations, which they undoubtedly had sufficient occasion of, the monk passionately impressed upon his companion of the need to transition to manufacturing than merely taking the easy way of trading raw materials or semi-finished goods. The former approach would help create jobs, add much greater value to the products then to be sold, and take the country ahead on the road to self-sufficiency and development. He also talked of training Indians not just in science, but also technology, so that the country’s requirements could be significantly fulfilled by its domestic manufacturing. Both of them knew it was not an easy dream in the days of a hostile regime. These suggestions surely had a strong resonance with the industrialist, who was probably already nursing the same ideas.

They alighted at their destination and bade each other goodbye, probably thinking that this would be their last meeting. It is quite likely that the industrialist did not pick up the monk’s name as the latter, till then, had the wont of introducing himself just as a Sanyasin, without a name.

Five years passed. The monk returned from the West after four years. He was given a stupendous welcome across several towns and cities throughout the subcontinent.

It was then that the industrialist wrote a letter to this old co-passenger:

Esplanade House,

Bombay.

23rd Nov. 1898

Dear Swami Vivekananda,

I trust, you remember me as a fellow- traveller on your voyage from Japan to Chicago. I very much recall at this moment your views on the growth of the ascetic spirit in India, and the duty, not of destroying, but of diverting it into useful channels.

I recall these ideas in connection with my scheme of Research Institute of Science for India, of which you have doubtless heard or read. It seems to me that no better use can be made of the ascetic spirit than the establishment of monasteries or residential halls for men dominated by this spirit, where they should live with ordinary decency and devote their lives to the cultivation of sciences –natural and humanistic. I am of opinion that, if such a crusade in favour of an asceticism of this kind were undertaken by a competent leader, it would greatly help asceticism, science, and the good name of our common country; and I know not who would make a more fitting general of such a campaign than Vivekananda. Do you think you would care to apply yourself to the mission of galvanizing into life our ancient traditions in this respect? Perhaps, you had better begin with a fiery pamphlet rousing our people in this matter. I would cheerfully defray all the expenses of publication.”

With kind regards, I am, dear Swami

Yours faithfully,

Jamshedji Tata

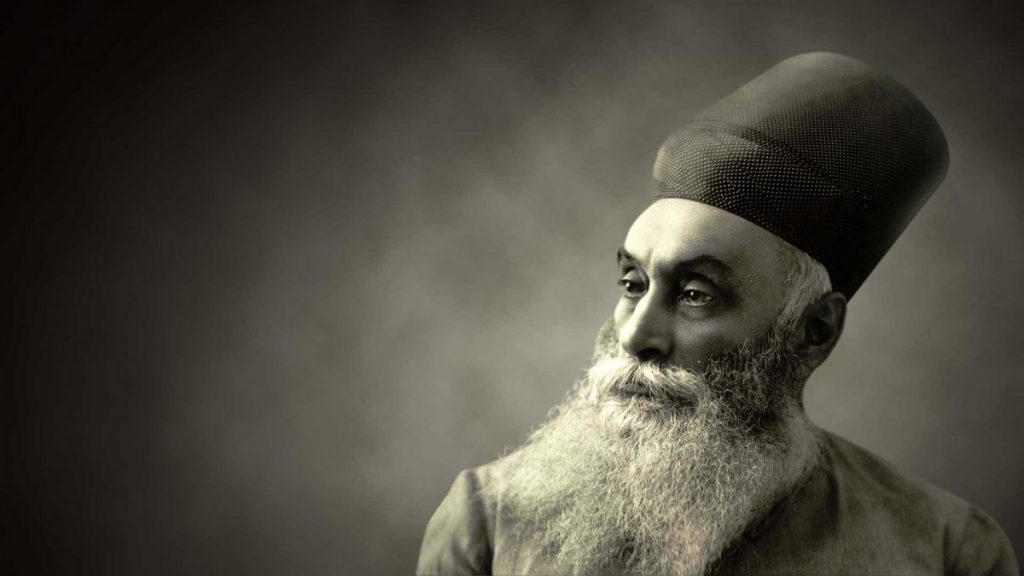

Tata, was referring in the letter to his pledge of a gift of 200,000 in pound sterling (about Rs 30 lakh then), widely reported nationally towards setting up a research institute to “induce the students of this country to undertake researches on the problems of tropical diseases or tropical chemistry, to investigate the vast and neglected materials of our national history and Indian philology” and “to found laboratories and libraries, where students may work under the direction of great teachers.”

The Swami, of course, could not directly take up the leadership of this venture due to his own preoccupation of setting up of a new, dynamic monastic order aimed at channelling the traditional ascetic spirit of spiritual practioners towards service of humanity. But he wished it well and, more importantly, also transmitted his enthusiasm regarding the project to some of his disciples.

Tata takes it up with the viceroy

Meanwhile Tata met the viceroy, Lord Curzon, immediately after the latter took office. The viceroy dismissed the idea as impractical. He thought Indians did not have the temperament of engaging in research in science, that the institute would not get enough competent candidates, and also expressed doubt regarding the employability prospects of students after such a training.

Following this, the Swami’s pre-eminent disciple, Sister Nivedita, began to actively campaign for the actualisation of this scheme by this great patriot-industrialist and wrote several articles in the English press championing it. As early as 1899 she wrote:

“We are not aware if any project is at once so opportune and so far-reaching in its beneficent effects was ever mooted in India, as that of the Post-Graduate Research University of Mr Tata. The scheme grasps the vital point of weakness in our national well-being with a clearness of vision and tightness of grip, the masterliness which is only equalled by the munificence of the gift with which it is ushered to the public.”

In due course, the government appointed an inquiry into this proposal by Sir William Ramsay in 1900. Ramsay, eminently well-known as a scientist, was to win the Nobel Prize in Chemistry four years later, for his discovery and separation of what he called the ‘inert gases’. His discovery led to the addition of a new column to the periodic table. Though brilliant as a scientist, Ramsay could not rise above the coloniser’s prejudice. In his submission, he shot down the proposal. One of his observations was the infeasibility of an institute which would combine scientific research with streams of humanities, as intended by Tata.

The viceroy and others also suggested that Tata make the gift and leave it to the best sense of the government to do what it felt was appropriate. Thus the matter remained in a deadlock.

Nivedita’s efforts to get the green light

Nivedita, while she was in London in 1901, also took up the issue with Sir George Birwood, an eminent official of the education department. She met with the same lack of will towards any initiative leading to avenues being opened for India’s self-reliance in science and research. Sir Birwood reiterated the establishment’s prejudice with regard to the Tata scheme as, in his opinion, even the three universities in the presidency towns had failed to produce an original mind since 1857, a remark that left Nivedita furious.

At this time Nivedita thought of rallying a wider public opinion on the subject and wrote to several leading world-thinkers, many of whom she was personally in touch with, requesting them to voice their thoughts on the desirability of such an institution. Among others, she got the leading American psychologist and philosopher of the day, William James of Harvard, who had the privilege of meeting and spending time with Vivekananda and used to address him as master. William James wrote, “With regard to Mr Tata’s scheme for promoting higher education in India, I am of the opinion that for the attainment of his object ….the management ought to be conducted entirely on national lines.” He suggested equal representation of all communities of India on the governing body of this institution, and freedom from government control.

She could also get the valuable advocacy of Patrick Geddes, arguably the greatest Scottish intellectual of last few centuries – a polymath with seminal inter-disciplinary work as a biologist, sociologist, environmentalist, and town-planner. It was to Geddes, when the former was troubled with a sore eye in Paris in 1900, that Vivekananda had said, “Professor, be mind-minded, not eye (I)-minded.”

Tata passed away in 1904, two years after Vivekananda did. His dream did not see the light of day during his lifetime. But the proposal was finally approved in 1909 by Lord Minto , who succeeded Lord Curzon as the viceroy. Though Tata’s choice for the venue of the institute was his own city of Bombay, later circumstances led it to be set up in Bangalore, following a gift of 370 acres by the ruler of Mysore state, Maharaja Krishnaraj Wadiyar. It is notable that the Maharaja’s father, H.H. Chamaraja Wadiyar, had been a devoted disciple of Vivekananda, and was instrumental in sending him to the West.

Though its final shape was not exactly in the form that Tata would have wanted (of having both science as well as humanities as its areas of focus), the Indian Institute of Science Bangalore (as the Tata Institute later came to be known as) has been at the forefront of scientific research in the country and, to a considerable extent, acted as the knowledge-incubator of a host of specialised institutions that came in its wake, like the Indian Institutes of Science and the Tata Institute of Fundamental Research.

While the fact of Vivekananda’s inspiring force behind the institute is rather less-known among the public at large, the contribution of that great selfless lover and servant of the country, Sister Nivedita, is almost completely forgotten and unacknowledged.